Principle of Mathematical Induction

What Does the Principle of Mathematical Induction State?

If a subset U of the set of natural numbers N contains zero and the successor of every element it contains, then U coincides with the entire set of natural numbers N.

This is one of Peano’s axioms for the natural numbers.

What Is the Principle of Induction Used For?

The principle of induction underpins one of the most powerful proof techniques in mathematics, known as proof by induction.

It allows us to prove that a statement or theorem holds across an infinite set of natural numbers without having to verify each case individually.

Proof by induction is closely linked to the idea of mathematical recursion.

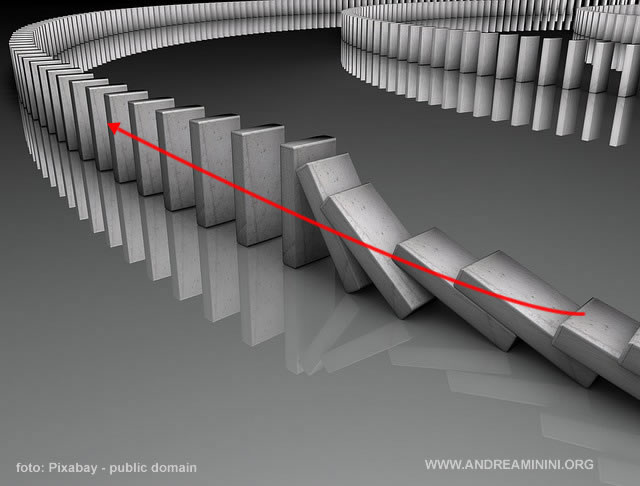

It’s often compared to the domino effect.

If you line up thousands of dominoes close together and push the first one over, they’ll all fall in sequence.

You don’t need to check each domino individually.

As long as they’re spaced correctly, they’ll all fall automatically.

How Does Proof by Induction Work?

- Consider a proposition P(n), where n ∈ N is a natural number, and an initial value n0.

- Base Case

Prove that P(n0) is true. - Inductive Hypothesis

Assume that P(n) is true for some arbitrary natural number n. - Inductive Step

Prove that if P(n) holds, then P(n+1) also holds. If this implication is established, then P(n) is true for all n ≥ n0.

If you need to prove a statement only for natural numbers greater than or equal to some starting point n0, then the base case should be checked for n0 rather than for zero.

$$ \begin{cases} P(n_0) \\ \\ P(n) \Rightarrow P(n+1) \end{cases} $$

It’s important to note that n0 doesn’t have to be zero; it could just as well be n0 = 1 or another starting value.

In fact, n0 is simply the smallest element in the set under consideration.

The next example should clarify how this works in practice.

Note. Before proceeding, it’s crucial to remember that induction does not discover the correct result - it only verifies whether a proposed statement is true. It’s always up to the mathematician to formulate the hypothesis to be proved. Also, induction is only applicable when the proposition depends on the natural numbers. This is an essential point not to overlook.

A Practical Example

Example 1

Let’s prove that the following proposition P(n) is divisible by 6 for all n ≥ 1:

where n is any natural number n ∈ N, with n ≥ 1.

$$ P(n) := n^3 + 5n $$

First, we verify the base case for the smallest element in the set.

Here, our set is the natural numbers, so n0 = 1.

We substitute n = 1 into P(n):

$$ P(1) = (1)^3 + 5(1) \\ P(1)= 1 + 5 \\ P(1)= 6 $$

The base case holds true since 6 is divisible by 6.

This satisfies the first condition of the principle of induction.

Note. If the base case were false, there’d be no point in continuing the proof. It’s critical to confirm the base case first because it’s often simpler than the inductive step.

Next, we check the inductive step.

By the inductive hypothesis, we assume that P(n) is true - that is, divisible by 6 - for some arbitrary natural number n:

$$ P(n) := n^3 + 5n \quad \text{(assumed divisible by 6)} $$

According to the principle of mathematical induction, if P(n) is true, then P(n+1) must also be true.

This is the statement we want to prove:

$$ P(n+1) := (n+1)^3 + 5(n+1) $$

where n+1 is the successor of n.

We now need to show that this implication indeed holds.

Note. The proposition P(n) is assumed true by hypothesis, but this doesn’t automatically guarantee that P(n+1) is true. That’s precisely what needs to be demonstrated: $$ P(n) \Rightarrow P(n+1) $$

There are several ways to prove this.

The simplest approach is to rewrite P(n+1) in terms of P(n), which we already know is divisible by 6 by hypothesis.

$$ P(n+1) := (n+1)^3 + 5(n+1) $$

$$ P(n+1) := n^3 + 3n^2 + 3n + 1 + 5n + 5 $$

$$ P(n+1) := (n^3 + 5n) + 3n^2 + 3n + 1 + 5 $$

We’ve successfully isolated P(n) within P(n+1).

This lets us write:

$$ P(n+1) := P(n) + 3n^2 + 3n + 6 $$

$$ P(n+1) := P(n) + 3n(n+1) + 6 $$

From this expression, we observe that:

- The term 3n(n+1) is divisible by 6 because n(n+1) is always even or a multiple of 2 for consecutive integers.

- The constant term +6 is obviously divisible by 6.

Therefore, the second condition of the principle of induction is met.

We have thus shown that P(n) is divisible by 6 for every n ≥ 1.

Example 2

Let’s prove that the sum of the first n powers of 2 equals 2n − 1:

$$ P(n) := 2^0 + 2^1 + 2^2 + 2^3 + \dots + 2^{n-1} = 2^n - 1 $$

First, we check the base case for n = 1.

The first term of the series is 20, and for n = 1 we get 21 − 1:

$$ P(1) := 2^0 = 2^1 - 1 $$

$$ P(1) := 1 = 2 - 1 $$

$$ P(1) := 1 = 1 $$

The base case is true, so we proceed.

By the inductive hypothesis, we assume the proposition holds for some integer n:

$$ P(n) := 2^0 + 2^1 + 2^2 + 2^3 + \dots + 2^{n-1} = 2^n - 1 $$

Now, we verify the inductive step for n+1:

$$ P(n+1) := 2^0 + 2^1 + 2^2 + 2^3 + \dots + 2^{(n+1)-1} = 2^{n+1} - 1 $$

We can express the left-hand side as:

$$ P(n+1) = \left(2^0 + 2^1 + \dots + 2^{n-1}\right) + 2^n $$

Applying the inductive hypothesis:

$$ P(n) = 2^n - 1 $$

So substituting, we get:

$$ P(n+1) = (2^n - 1) + 2^n $$

$$ P(n+1) = 2 \cdot 2^n - 1 $$

$$ P(n+1) = 2^{n+1} - 1 $$

This confirms that P(n+1) holds.

Therefore, the proposition P(n) is true for all natural numbers n.

And so on.