Pressure

Pressure (p) is a physical quantity that quantifies how strongly a force acts on a surface. It is defined as the ratio between the component of the force perpendicular to the surface, $ F_{\perp} $, and the area $ A $ over which that force is applied. $$ p = \frac{F_{\perp}}{A} $$

The force must act perpendicular to the surface; otherwise, only its normal component contributes to the pressure.

When the force is already perpendicular to the surface, the definition simplifies to:

$$ p = \frac{F}{A} $$

This relationship immediately shows that pressure is directly proportional to the applied force ( F ) and inversely proportional to the area ( A ).

Consequently, doubling the pressure can be achieved either by doubling the force or by reducing the area by half. In both cases, the resulting pressure is identical.

$$ 2p = \frac{2F}{A} = \frac{F}{\frac{A}{2}} $$

Therefore, the same force applied over a smaller surface produces a higher pressure.

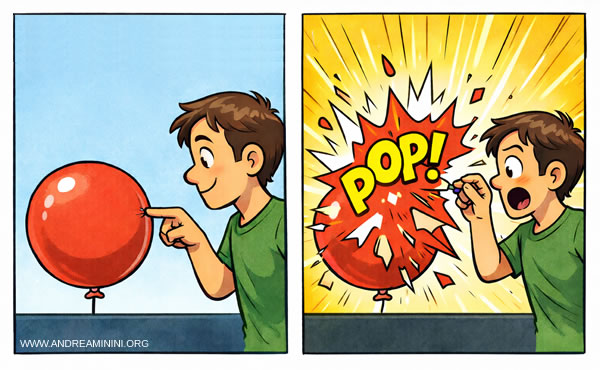

For instance, when a balloon is touched with a finger, the pressure is relatively low because the force is spread over a comparatively large contact area. The balloon deforms but does not burst. If the same force is applied with a pin, however, the pressure becomes very high because the force is concentrated on a much smaller area, and the balloon bursts.

In other words, when a force is applied to a surface, its effect depends not only on the magnitude of the force, but also on the area over which that force is distributed. This is why a balloon does not burst when pressed with a finger, yet breaks easily when touched with a pin.

Pressure is a fundamental quantity for understanding how forces are transmitted within solids and fluids.

The unit of measurement of pressure

Pressure is a scalar quantity, since it is completely specified by a numerical value representing its magnitude together with a unit of measurement.

In the International System of Units (SI), the unit of pressure is the pascal (Pa).

$$ 1 \ \text{Pa} = 1 \ \frac{\text{N}}{\text{m}^2} $$

This means that a pressure of 1 pascal corresponds to the effect of a force of 1 newton uniformly distributed over an area of 1 square meter.

The name "pascal" honors the French physicist Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), whose work laid the foundations for the study of pressure in fluids.

Note. From the standpoint of dimensional analysis, pressure is the ratio of a force to an area, that is, a length (L) squared: \[ p = \frac{[F]}{[L^2]} \] The force \( F \) has dimensions \([M \cdot L \cdot T^{-2}] \), corresponding to mass times acceleration. The area has dimensions \([L^2] \). Substituting into the expression gives: \[ [p] = \frac{[M \cdot L \cdot T^{-2}]}{[L^2]} = [M \cdot L^{-1} \cdot T^{-2}] \] This is the physical dimension of the pascal and reflects the concrete physical meaning of pressure.

Pressure is measured using instruments known as pressure gauges or manometers. Different types are employed depending on the nature of the fluid and the pressure range of interest, including gases, liquids, and both low- and high-pressure regimes.

An example calculation

The objective is to determine the pressure exerted on the surface of a balloon when a force of \( 2.6 \ \text{N} \) is applied, using:

- a) a finger, given that the contact area is \( 1.1 \cdot 10^{-4} \ \text{m}^2 \)

- b) a pin, given that the area of the tip is \( 2.1 \cdot 10^{-7} \ \text{m}^2 \)

Furthermore, knowing that the balloon bursts at a pressure of \( 4.1 \cdot 10^{5} \ \text{Pa} \), what is the minimum force required to burst the balloon with a pin? What is the corresponding minimum force when using a finger?

a] Pressure exerted by the finger

A force \( F = 2.6 \ \text{N} \) is applied over an area \( A = 1.1 \cdot 10^{-4} \ \text{m}^2 \), corresponding to the contact area of the finger.

The pressure exerted by the finger is therefore:

\[ p = \frac{F}{A} = \frac{2.6 \ \text{N}}{1.1 \cdot 10^{-4} \ \text{m}^2} \]

Recalling that one pascal is defined as $ Pa = \frac{\text{N}}{\text{m}^2} $, and carrying out the calculation, the result is:

\[ p \approx 2.36 \cdot 10^{4} \ \text{Pa} \]

The pressure exerted by the finger is relatively low because the applied force is spread over a comparatively large area.

b] Pressure exerted by the pin

In this case, the same force \( F = 2.6 \ \text{N} \) is applied over an area \( A = 2.1 \cdot 10^{-7} \ \text{m}^2 \), corresponding to the tip of the pin.

The pressure exerted by the pin is therefore:

\[ p = \frac{F}{A} = \frac{2.6 \ \text{N}}{2.1 \cdot 10^{-7} \ \text{m}^2} \]

Recalling that one pascal is $ Pa = \frac{\text{N}}{\text{m}^2} $, and performing the calculation, the result is:

\[ p \approx 1.24 \cdot 10^{7} \ \text{Pa} \]

Here, the pressure is several orders of magnitude greater because the same force is concentrated over an extremely small area.

c] Minimum force required to burst the balloon with a pin

Given that the bursting pressure of the balloon is \( p = 4.1 \cdot 10^{5} \ \text{Pa} \), the definition of pressure \( p = \frac{F}{A} \) can be used to determine the force:

\[ F = pA \]

Substituting the value of the bursting pressure and the area of the pin tip \( A = 2.1 \cdot 10^{-7} \ \text{m}^2 \) into the formula gives:

\[ F = (4.1 \cdot 10^{5} \ \text{Pa}) \cdot (2.1 \cdot 10^{-7} \ \text{m}^2) \]

Recalling that one pascal is $ Pa = \frac{\text{N}}{\text{m}^2} $:

\[ F = (4.1 \cdot 10^{5} \ \frac{\text{N}}{\text{m}^2}) \cdot (2.1 \cdot 10^{-7} \ \text{m}^2) \]

\[ F = (4.1 \cdot 10^{5} \ \text{N}) \cdot (2.1 \cdot 10^{-7} ) \]

\[ F = 8.61 \cdot 10^{-2} \ \text{N} \]

Therefore, the minimum required force is:

\( F_{\min} \approx 0.086 \ \text{N} \)

This is the minimum force needed to burst the balloon using a pin.

d] Minimum force required to burst the balloon with a finger

The procedure is the same. Starting once again from the definition of pressure \( p = \frac{F}{A} \), the force can be expressed as:

\[ F = pA \]

The bursting pressure is \( p = 4.1 \cdot 10^{5} \ \text{Pa} \), and the contact area of the finger is \( A = 1.1 \cdot 10^{-4} \ \text{m}^2 \).

\[ F = (4.1 \cdot 10^{5} \ \text{Pa}) \cdot (1.1 \cdot 10^{-4} \ \text{m}^2) \]

Recalling that one pascal is $ Pa = \frac{\text{N}}{\text{m}^2} $:

\[ F = (4.1 \cdot 10^{5} \ \frac{\text{N}}{\text{m}^2}) \cdot (1.1 \cdot 10^{-4} \ \text{m}^2) \]

\[ F = (4.1 \cdot 10^{5} \ \text{N}) \cdot (1.1 \cdot 10^{-4} ) \]

The powers of ten are combined \( 10^{5} \cdot 10^{-4} = 10^{1} \), and the numerical coefficients are multiplied \( 4.1 \cdot 1.1 = 4.51 \).

\[ F = 4.51 \cdot 10^{1} \ \text{N} \]

Therefore, the minimum required force is:

\[ F_{\min} \approx 45 \ \text{N} \]

This example clearly illustrates that pressure depends not only on the magnitude of the applied force, but, more importantly, on how that force is distributed over the surface.

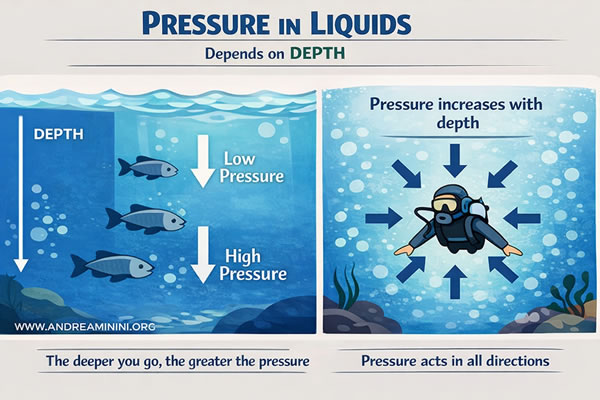

Pressure in Fluids

The pressure in a fluid is defined as the force per unit area exerted by the fluid on the walls of its container, on immersed bodies, and on adjacent portions of the fluid itself.

Pressure always acts normal to the surface on which it is applied, whether that surface belongs to the container walls, to a submerged object, or to an idealized surface imagined within the fluid.

When a fluid is in equilibrium, that is, when it is at rest, pressure exhibits a fundamental property: at any point within the fluid, its magnitude is the same in all directions.

To clarify this property, consider an arbitrary point inside a fluid in equilibrium and an imaginary surface passing through that point. On each side of the surface, pressure forces act perpendicular to it. These forces have equal magnitude and opposite sense, and therefore exactly balance one another.

If the orientation of the imaginary surface is changed, the direction of the force exerted by the fluid changes accordingly, but the magnitude of the pressure remains unchanged. Hence, pressure is independent of surface orientation and has the same value in every direction.

Note. Because pressure is not associated with any preferred direction, it is not a vector quantity. Pressure is a scalar quantity.

Consequently, at every point in a fluid at equilibrium, equal and opposite pressure forces act in all directions.

If this condition were not satisfied, the forces would not balance, a resultant force would appear, and the fluid would begin to move.

For this reason, the isotropy of pressure is a necessary condition for the mechanical equilibrium of fluids.

Difference between pressure in solids and liquids

In solids, pressure depends on the magnitude of the applied force and the contact area over which that force is distributed.

For instance, a person wearing sneakers exerts less pressure on the ground than the same person wearing high heels, since the contact area is considerably smaller.

In liquids, by contrast, pressure is mainly determined by depth. The deeper the point within the fluid, the greater the pressure exerted by the liquid. This is because the weight of the overlying fluid column increases with depth.

Hence, in a fluid at rest, pressure increases with depth and, at any given point, acts equally in all directions.

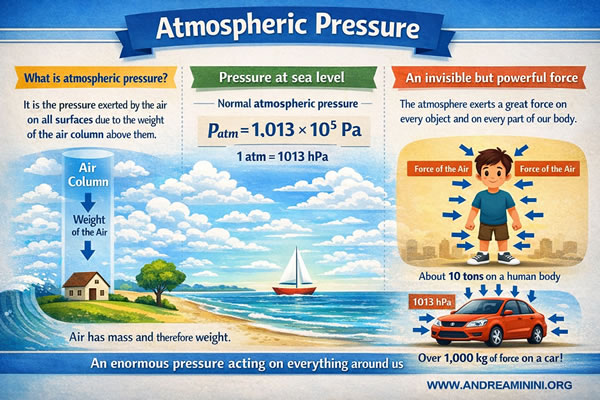

Atmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure is the pressure exerted by the air on all surfaces as a consequence of the weight of the overlying column of air.

Air possesses mass and therefore weight. At sea level, standard atmospheric pressure is approximately:

\[ p_{at} = 1.013 \cdot 10^5 \ \text{Pa} \]

Although we are not directly aware of it, the atmosphere exerts a substantial force on every object and on every part of the human body.

Additional examples

Example 1

A ball with a gauge (relative) internal pressure of \( p = 8.0 \times 10^4 \ Pa \) is pressed against the floor by a force \( F = 40 \ N \) and then rebounds. What is the contact area between the ball and the floor?

Begin with the definition of pressure

$$ p = \dfrac{F}{A} $$

Solving for the area when the force and pressure are known

$$ A = \dfrac{F}{p} $$

Substitute the given values \( F = 40 \ N \) and \( p = 8.0 \times 10^4 \ Pa \)

$$ A = \dfrac{40}{8.0 \times 10^4} = 5.0 \times 10^{-4} \ m^2 $$

Convert to square centimeters

$$ 5.0 \times 10^{-4} \ m^2 = 5.0 \ cm^2 $$

Therefore, the contact area is 5 cm2.

What is the diameter of the contact area?

Assume the contact region is circular. Use the area formula for a circle

$$ A = \pi \left(\dfrac{d}{2}\right)^2 $$

Solving for the diameter \( d \)

$$ \left(\dfrac{d}{2}\right)^2 = \dfrac{A}{\pi} $$

$$ d = 2 \sqrt{\dfrac{A}{\pi}} $$

Substitute the contact area

$$ d = 2 \sqrt{\dfrac{5.0 \times 10^{-4}}{\pi}} $$

Evaluate the expression inside the square root

$$ \dfrac{5.0 \times 10^{-4}}{\pi} \approx 1.59 \times 10^{-4} $$

Take the square root

$$ \sqrt{1.59 \times 10^{-4}} \approx 0.0126 \ m $$

Multiply by 2

$$ d \approx 2 \times 0.0126 = 0.0252 \ m $$

Convert to centimeters

$$ d = 2.52 \ cm \approx 2.5 \ cm $$

Hence, the contact diameter is approximately \( d \approx 2.5 \ cm \).

What is the ball's absolute internal pressure?

The absolute pressure is the sum of the gauge pressure and atmospheric pressure

$$ p_{abs} = p_{gauge} + p_{atm} $$

The given pressure \( p = 8.0 \times 10^4 \ Pa \) corresponds to the gauge pressure \( p_{gauge} \).

Using \( p_{atm} \approx 1.0 \times 10^5 \ Pa \)

$$ p_{abs} = 8.0 \times 10^4 \ Pa + 1.0 \times 10^5 \ Pa $$

$$ p_{abs} = 0.8 \times 10^5 \ Pa + 1.0 \times 10^5 \ Pa $$

$$ p_{abs} = 1.8 \times 10^5 \ Pa $$

Thus, the absolute internal pressure is approximately 1.8 atm.

And so on.