Quarks

Quarks are the fundamental constituents of protons and neutrons - the smallest known building blocks of matter.

Who discovered quarks?

The concept of quarks was first introduced in the 1960s by American physicist Murray Gell-Mann. The first experimental evidence emerged shortly after, and in 1963, the up and down quarks were detected.

What exactly are quarks?

Gell-Mann proposed that protons and neutrons are not truly elementary particles. Instead, they are composite particles made up of smaller components called quarks.

Protons and neutrons - collectively known as nucleons - form the atomic nucleus. However, they are not fundamental particles, as they can be broken down into constituent quarks.

Where are quarks found?

Quarks cannot exist in isolation under normal conditions. They are only observable when confined within other elementary particles, such as nucleons.

What binds quarks together within a particle?

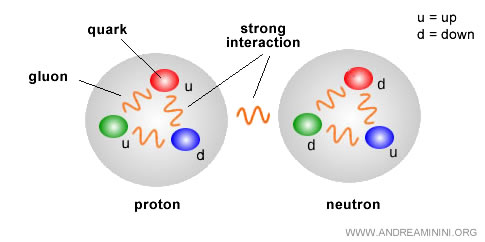

Within nucleons, quarks are held together by the strong nuclear force, one of the four fundamental forces in nature.

This same force is also responsible for holding protons and neutrons together within the atomic nucleus.

Are all elementary particles made of quarks?

No. Only certain families of elementary particles are composed of quarks.

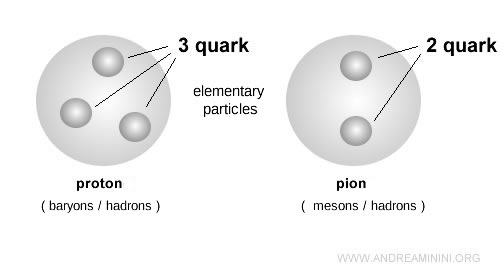

Example: Hadrons are made of quarks. This group includes nucleons and is subdivided into two categories: baryons and mesons.

How many quarks make up an elementary particle?

Some elementary particles are made of two quarks, while others are composed of three.

Baryons (such as neutrons, protons, lambda, sigma, and xi particles) contain three quarks, whereas mesons (like pions and kaons) are formed from a quark-antiquark pair.

Which elementary particles contain no quarks?

Some elementary particles are not composed of quarks at all.

Leptons (including the electron, neutrino, muon, and tau) and force carriers (such as the photon, gluon, bosons, and graviton) are quark-free particles.

What are the main properties of quarks?

Each quark has a specific mass, electric charge, spin, and a quantum property known as color charge. Based on these characteristics, six distinct types of quarks have been identified, each referred to by its flavor.

What is quark flavor?

Flavor is a term that refers to a specific combination of quantum properties assigned to a quark. The six flavors of quarks are: Up, Down, Strange, Charm, Bottom (Beauty), and Top.

Note: The word "flavor" here has nothing to do with taste. It’s simply a whimsical term used in particle physics to distinguish between quark types based on their quantum characteristics.

Quarks are organized into three generations, each with increasing mass and energy.

What is a quark’s electric charge?

Quarks carry either a positive or negative electric charge, but unlike electrons or protons, their charges are fractional: either one-third (1/3) or two-thirds (2/3) of the elementary charge.

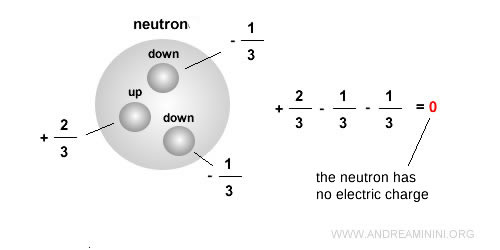

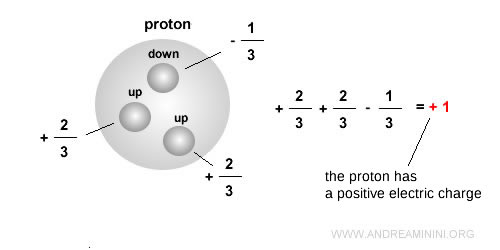

The total electric charge of a particle is the sum of its quarks’ charges, which always adds up to an integer (+1, 0, or -1) - defining the net charge of protons and neutrons.

Real-world examples

A neutron consists of two Down quarks (-1/3) and one Up quark (+2/3). The total charge is zero, making the neutron electrically neutral.

A proton, on the other hand, consists of two Up quarks (+2/3) and one Down quark (-1/3). The total charge is +1.

This is why protons carry a positive electric charge.

What is spin in quarks?

Spin is a quantum property that can take positive or negative values. Quarks are fermions, meaning they have a half-integer spin of +1/2.

What does spin mean?

Spin describes a quark’s intrinsic angular momentum - essentially, how it “rotates” on its own axis. A spin of +1/2 indicates one orientation; -1/2 indicates the opposite.

This quantum spin contributes to the magnetic and structural properties of the particles quarks compose.

Note. The illustration is a didactic simplification. Quarks are not tiny spheres that spin in place, and spin itself is not a literal rotational motion. Elementary particles have no physical size and no actual axis around which they could rotate. The values +1/2 and -1/2 denote the eigenvalues of the spin operator along a chosen measurement axis, not two opposite directions of rotation. The visual analogy is used only to provide an intuitive sense of the two spin states. In reality, spin is an intrinsically quantum property with no classical counterpart.

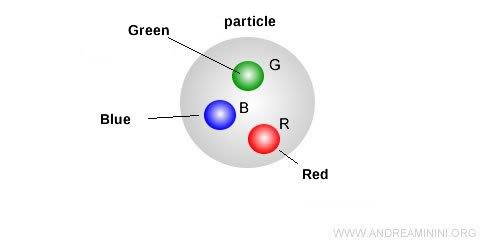

What is color in quarks?

Quarks come in three "colors": red, green, and blue.

These are not literal colors, of course. "Color" is just a metaphorical term used to represent a quantum property related to the strong interaction.

What role does color play in quarks?

Color helps explain how quarks interact and combine.

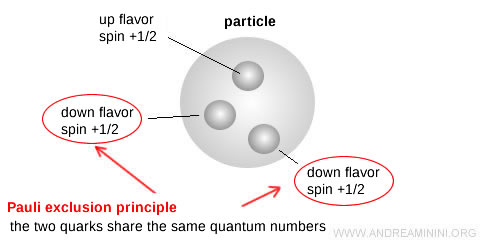

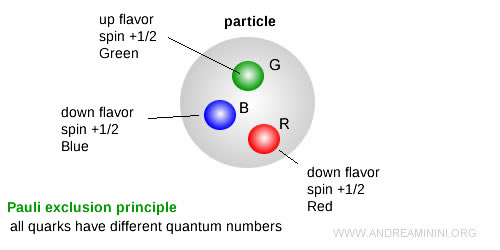

Physicists noticed that certain quarks within particles seemed to share identical quantum states.

This would violate the Pauli exclusion principle, which prohibits two identical fermions from occupying the same quantum state. At least one quantum number must differ.

This principle applies to quarks as well: you can't form a particle from identical quarks. Each quark must differ in at least one quantum property.

To account for this, physicists introduced color charge (red, green, blue) as an additional quantum number.

This property ensures that combinations of quarks in particles adhere to the Pauli principle by distinguishing otherwise identical quarks.

What are antiquarks?

Every quark has a corresponding antiquark with opposite properties - defined by an anti-flavor and anti-color.

Example: The Up quark has a charge of +2/3. Its antiquark counterpart carries a charge of -2/3. The same applies to all other quarks.

Why We Can’t Detect a Free Quark

In nature, quarks are never found in isolation due to a phenomenon known as quark confinement, a key prediction of Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD).

Quarks interact via the strong force, transmitted by particles called gluons, which operate through a property known as color charge. You can think of it as a highly unusual form of “magnetism” that binds quarks together with extraordinary strength.

Note. The golden rule is that particles must be “white,” meaning neutral in terms of color charge. In baryons, this is achieved by combining three quarks, each with a different color (red, green, and blue). In mesons, the pairing is between a quark and its complementary antiquark (for example, green and anti-green). In both cases, the combination is color-neutral. If you tried to put together two quarks of the same color - say, both green - you’d end up with a “colored” state rather than a neutral one, causing the color fields to become enormous and unstable. Nature immediately reshuffles them into a configuration that results in overall neutrality.

Unlike the electric force, which weakens with distance, the strong force actually grows stronger the farther apart quarks are pulled.

It’s a bit like stretching a rubber band between two quarks - the more you pull, the greater the tension. If you try to separate them, the energy stored in the “string” of gluons rises sharply.

Once that energy exceeds a certain threshold, it becomes more favorable for the vacuum itself to create a new quark - antiquark pair than to allow the original quarks to drift apart.

The result is that instead of isolating a free quark, you end up producing new composite particles (hadrons), such as mesons or baryons.

This is why free quarks have never been directly observed in nature. Every quark we detect is confined within a composite particle like a proton, neutron, pion, and so forth.

To study quarks, we have to do so indirectly - by smashing particles together at high energies and analyzing the resulting particle jets.

How this differs from electric charge. In QED (Quantum Electrodynamics), the photons that mediate the force have no electric charge, so they don’t interact with each other. In QCD, however, gluons themselves carry color charge, which means they do interact with one another. This makes the strong force far more complex and inherently self-interacting. Gluons are combinations of a color and an anticolor. For example, a red - anti-green gluon can change a green quark into a red quark, altering its “color.” This continuous exchange of gluons is what literally “glues” quarks together inside hadrons such as protons and neutrons.

And so on.