Stern-Gerlach Experiment

The Stern - Gerlach experiment provided the first direct evidence that spin is quantized rather than continuous. It revealed the fundamentally non-classical character of angular momentum in quantum systems.

In 1922, Otto Stern and Walther Gerlach designed an experiment to test the spatial quantization of angular momentum predicted in the Bohr - Sommerfeld model. Their central question was whether a particle's angular momentum could adopt any orientation in space or whether its allowed orientations were discrete.

What does the experiment involve?

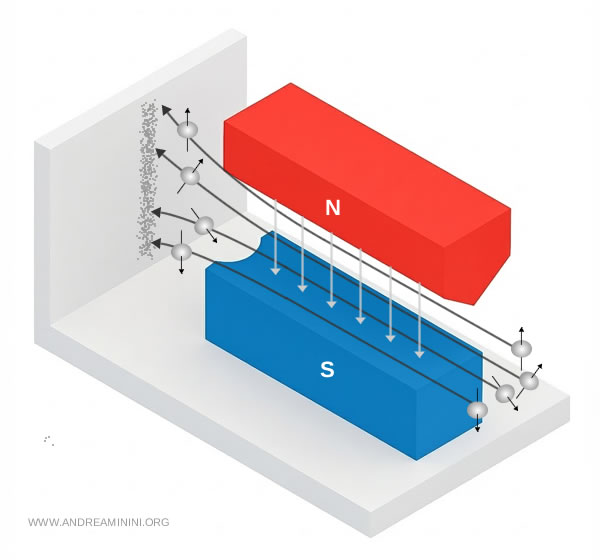

They passed a beam of neutral silver atoms through the gap between the poles of a specially constructed magnet. A soot-coated detector placed beyond the magnet recorded where the atoms struck.

According to classical physics, an atom with a magnetic moment moving through a non-uniform magnetic field should experience a force that deflects it upward or downward depending on the orientation of its magnetic moment.

If the atoms in the beam possessed all possible orientations, the detector should reveal a continuous vertical smear, a smooth band stretching from bottom to top.

This is precisely what Stern and Gerlach expected to observe.

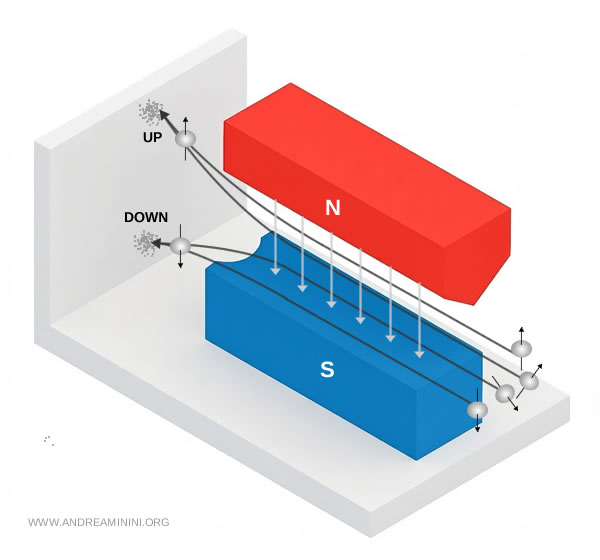

The actual observation, however, was strikingly different. Instead of a continuous distribution, the detector showed two sharp, well-separated spots. No intermediate intensities appeared.

The atoms behaved as if the projection of their magnetic moment along the field axis could assume only two discrete eigenvalues.

Here is the pattern that Stern and Gerlach actually recorded.

In quantum language, the measurement forced each atom's wavefunction into one of two allowed eigenstates of the angular momentum projection operator, conventionally named spin up and spin down.

Note. This reflects the same structure encountered in wave - particle duality. A quantum system evolves as a superposition of possibilities until a measurement is performed, which selects a single eigenvalue of the observable in question.

What accounts for this behavior?

Not long after the experiment, it became clear that the observed splitting could not be explained by orbital angular momentum alone.

The decisive conceptual shift came when Goudsmit and Uhlenbeck proposed that the electron carries an intrinsic form of angular momentum unrelated to any literal rotation in physical space. This intrinsic quantity became known as spin.

Spin is a fundamental quantum number, akin to charge or mass. It is not a mechanical motion and cannot be pictured using classical analogies. No geometric model captures its essence because it is not a spatial rotation.

In short, spin is not something a particle performs. It is an intrinsic part of what the particle is.

Note. Despite common illustrations, spin is not the rotation of a tiny sphere. Spin-1/2 particles provide a clear demonstration of this: after a 360° rotation, they do not return to their original quantum state but instead to its negative.

A full 720° rotation is required to recover the initial state. Classical mechanics knows nothing like this, since a rigid body always returns to its initial configuration after a single 360° turn.

For the electron, the spin quantum number is $ \frac{1}{2} $. The projection of this spin along any chosen axis can take only two eigenvalues:

- spin up

- spin down

The Stern - Gerlach experiment was, in essence, a direct measurement of this quantized projection.

The result helped establish the modern framework of quantum states and the classification of particles by spin:

- spin 1/2 for electrons and quarks

- spin 1 for gauge bosons

- spin 0 for the Higgs boson

- spin 2 for the hypothetical graviton

The two-spot splitting observed in 1922 provided unmistakable evidence of spin quantization. From this property arise the distinction between fermions and bosons and the Pauli exclusion principle.

Fermions have half-integer spin values (such as 1/2 or 3/2), while bosons possess integer spin (0, 1, 2).

Despite its apparent simplicity, the Stern - Gerlach apparatus exposed a profound truth at the foundation of quantum theory: the microscopic world is quantized, not continuous.

And with that, the modern understanding of quantum mechanics began to take shape.