Momentum in Physics

What is momentum?

Momentum is defined as the product of an object’s mass (m) and its velocity (v). $$ \vec{p} = m \cdot \vec{v} $$

It’s a vector quantity because it results from multiplying a scalar (mass) by a vector (velocity).

Unlike velocity on its own, momentum also accounts for the mass of the moving object.

Why is it important?

Momentum tells us how much force is required to bring a moving object to rest in a given time.

To stop an object, its momentum must be reduced to zero. The greater the initial momentum, the more force is needed-assuming the stopping time is the same.

$$ \vec{F} = \vec{p} = m \cdot \vec{v} $$

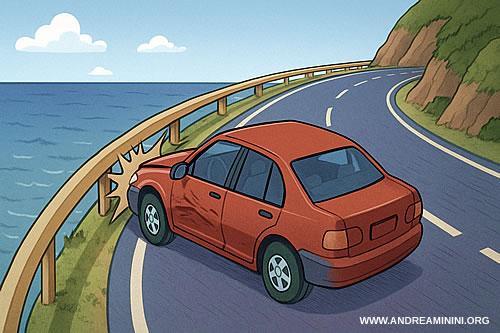

For example, a highway guardrail must be designed to slow down and stop a car that veers off the road.

Momentum also gives us a measure of the impact a moving object can have when it collides or interacts with something else.

A bowling ball, for instance, can topple pins with ease even at low speed thanks to its large mass and therefore high momentum. By contrast, a ping-pong ball, despite moving much faster, barely makes a dent because its tiny mass gives it almost no momentum.

The unit of momentum. We can determine the unit of momentum by analyzing the dimensions in its formula: $$ \vec{p} = m \cdot \vec{v} = [M] \cdot [V] = [M] \cdot \frac{[L]}{[T]} $$ The SI unit of mass [M] is the kilogram, length [L] is the meter, and time [T] is the second. So the unit of momentum is kg·m·s-1. $$ \vec{p} = [M] \cdot \frac{[L]}{[T]} = kg \cdot \frac{m}{s} = kg \cdot m \cdot s^{-1} $$ Momentum can also be expressed in newton-seconds, since 1 N = 1 kg·m·s-2: $$ \vec{p} = [M] \cdot \frac{[L]}{[T]} = (kg \cdot m \cdot s^{-2}) \cdot s = Ns $$ This is the same unit as the impulse of a force.

A practical example

Example 1

A car has a mass of $m = 1000 \,\text{kg}$ and is traveling at $v = 20 \,\text{m/s}$ (about 72 km/h).

Its momentum is twenty thousand kilogram-meters per second:

$$ p = m v = 1000 \cdot 20 = 20{,}000 \,\text{kg·m/s} $$

To stop it, we must reduce this momentum to zero. The required force depends on the stopping time $ \Delta t $.

$$ F = \frac{\Delta p}{\Delta t} $$

For instance, if the car is stopped in $\Delta t = 5 \,\text{s}$, the average force applied is 4000 N for 5 seconds.

$$ F = \frac{\Delta p}{\Delta t} = \frac{20{,}000}{5} = 4{,}000 \,\text{N} $$

If, instead, the car is brought to a halt in just $ \Delta t = 0.1 \,\text{s}$, the required force skyrockets:

$$ F = \frac{\Delta p}{\Delta t} = \frac{20{,}000}{0.1} = 2{,}000{,}000 \,\text{N} $$

This explains why sudden crashes generate enormous forces and cause severe damage, whereas gradual braking spreads the force over a longer time and makes the impact far less destructive.

Example 2

A bowling ball has a mass of $m_b = 7 \,\text{kg}$ and rolls at a modest speed of $v_b = 2 \,\text{m/s}$.

Its momentum is about 14 kg·m/s:

$$ p_b = m_b \cdot v_b = 7 \cdot 2 = 14 \,\text{kg·m/s} $$

So even at low speed, the bowling ball carries enough momentum to knock down pins easily.

A ping-pong ball, by contrast, has a mass of only $m_p = 0.0027 \,\text{kg}$ but can travel very quickly, at about $v_p = 20 \,\text{m/s}$.

Its momentum is only 0.054 kg·m/s:

$$ p_p = m_p \cdot v_p = 0.0027 \cdot 20 \approx 0.054 \,\text{kg·m/s} $$

In short, even moving extremely fast, the ping-pong ball carries so little momentum that when it strikes a pin, it barely moves it at all.

This shows why momentum is crucial: when evaluating the effect of a moving body in a collision, what matters is not just its speed, but its mass as well.

Constant vs. Variable Mass

In most classical mechanics problems, a body’s mass is assumed to be constant. In that case, momentum is simply:

$$ \vec{p} = m \vec{v} $$

Here the mass $m$ is fixed and independent of time.

There are, however, situations where mass changes with time.

Example. A clear case is a rocket expelling fuel: as the propellant is ejected, the rocket’s mass decreases during flight.

In such cases, Newton’s second law must be applied in its more general form:

$$ \vec{F} = \frac{d\vec{p}}{dt} = \frac{d}{dt}(m\vec{v}) $$

Here mass is itself a time-dependent quantity.

$$ \vec{F} = m \frac{d\vec{v}}{dt} + \vec{v}\,\frac{dm}{dt} $$

This expression makes it clear that a change in mass influences motion just as acceleration does.

Example. A simple but intuitive case is a car: at the start of a trip the fuel tank is full, while by the end it is nearly empty. The vehicle’s total mass is therefore slightly lower. In practice the difference is small, but the principle remains valid. In problems where mass changes significantly (rockets, fluid jets, sand pouring from a container, etc.), momentum must always be treated in this general form.

At speeds close to that of light, we must also account for relativistic effects: according to Einstein’s special relativity, a body’s inertia increases with velocity.

Relativistic Momentum

When an object’s speed becomes comparable to the speed of light, classical mechanics no longer provides an accurate description of its motion.

In Einstein’s special theory of relativity, the rest mass $m_0$ remains constant, but the definition of momentum takes on a new, relativistic form:

$$ \vec{p} = \gamma m_0 \vec{v} \qquad\text{where}\qquad \gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}}} $$

At everyday speeds, $\gamma \approx 1$, so the relativistic expression naturally reduces to the familiar classical formula.

As the velocity approaches the speed of light ($v \to c$), however, the Lorentz factor $\gamma$ grows without limit, and the momentum increases accordingly. This is why no object with a finite rest mass can ever be accelerated to the speed of light.

Note. In earlier treatments, physicists often introduced the idea of relativistic mass, defined as $ m_{\text{rel}} = \gamma m_0 $, to account for the growth of momentum at high speeds. Modern physics, however, keeps the rest mass $m_0$ fixed and attributes the increase in $\vec{p}$ entirely to the Lorentz factor $\gamma$.

In the relation $ \vec{p} = \gamma m_0 \vec{v} $, the term $\gamma \vec{v}$ has the same mathematical structure as the proper velocity $\vec{\eta} = d\vec{x}/d\tau$, defined with respect to the object’s proper time $\tau$.

Here, though, it represents the spatial component of the four-velocity $ U^\mu $:

$$ U^\mu = (\gamma c,\ \gamma \vec{v}) = (\gamma c,\ \gamma v_x, \gamma v_y, \gamma v_z ) $$

The spatial part coincides with the $\gamma \vec{v}$ factor in the expression for $\vec{p}$, yet it belongs to a four-dimensional invariant quantity-one that remains the same for all inertial observers.

Thus, the conservation of the four-momentum $P^\mu = m_0 U^\mu$ guarantees the conservation of both momentum and energy across every inertial reference frame.

Link Between Momentum and Force

Force is defined as the time derivative of momentum: $$ \vec{F} = \frac{d \ \vec{p}}{dt} $$

In this way, knowing a body’s momentum allows us to determine the force required to slow it down or bring it to rest.

The formula $F = dp/dt$ is simply a more general statement of Newton’s second law $F = ma$.

Derivation

Assume constant mass:

$$ \vec{p} = m \cdot \vec{v} $$

From Newton’s second law, force equals mass times acceleration:

$$ \vec{F} = m \cdot \vec{a} $$

Since acceleration $a = dv/dt$, we have:

$$ \vec{F} = m \cdot \frac{d\vec{v}}{dt} $$

But with constant $m$, this is equivalent to:

$$ \vec{F} = \frac{d(m\vec{v})}{dt} = \frac{d\vec{p}}{dt} $$

Explanation. The derivative of momentum with respect to time is $$ D[ \vec{p} ] = D[ m \cdot \vec{v} ] $$ With $m$ constant, $$ D[ \vec{p} ] = m \cdot D[ \vec{v} ] $$

and so forth.