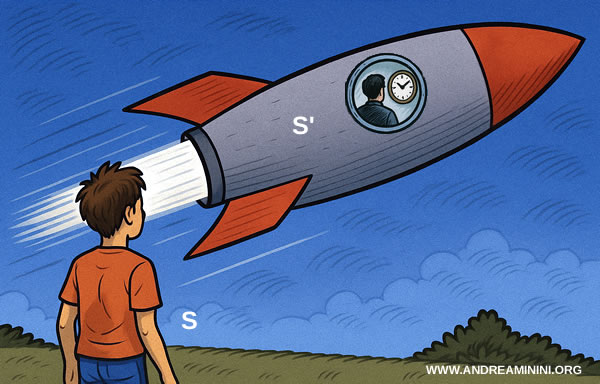

Difference between proper time and lab time

In special relativity, proper time is the time measured by a clock moving together with the observed object. Lab time, on the other hand, is the time measured by a clock in the inertial frame of the observer.

The distinction comes from Einstein’s principle of relativity: time is not absolute; it depends on the chosen frame of reference and its motion.

Put simply, every observer has their own “personal time,” valid only within their reference frame.

For instance, a clock aboard a body in uniform motion (say, a spaceship) traveling at speeds close to that of light will tick more slowly than a clock on Earth.

The relationship between the two time measures can be expressed as:

$$ t = \gamma \tau $$

In this expression, gamma ($\gamma$) denotes the Lorentz factor.

$$ \gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}}} $$

Accordingly, the equation can be rewritten in its full form as:

$$ t = \frac{\tau}{\sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}}} $$

where the symbols mean:

- $t$ is the lab time, the time measured by a stationary observer;

- $\tau$ is the proper time, the time measured in the moving system;

- $v$ is the object’s velocity relative to the observer;

- $c$ is the speed of light in a vacuum.

The formula shows that when $v = 0$, meaning the object is at rest, $t = \tau$: both clocks keep the same time.

As $v$ increases, $t > \tau$: lab time runs ahead of proper time.

And in the limit as $v \rightarrow c$, $\sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}} \rightarrow 0$, so $t \rightarrow \infty$: proper time nearly comes to a halt compared to lab time.

A practical example

Suppose the spaceship is traveling at $v = 0{,}8c$.

A clock on board records a proper time interval of:

$$ \tau = 1{,}0 \text{ s} $$

Now let’s compute the lab time on Earth:

$$ t = \frac{1{,}0}{\sqrt{1 - (0{,}8)^2}} = \frac{1{,}0}{\sqrt{1 - 0{,}64}} = \frac{1{,}0}{\sqrt{0{,}36}} = \frac{1{,}0}{0{,}6} = 1{,}67 \text{ s} $$

This means that for every second ticking on the spaceship’s clock (point C), 1.67 seconds pass on Earth (point A).

Note. Time dilation is not just a theoretical prediction. It has been experimentally confirmed - for instance, by comparing atomic clocks carried on airplanes and satellites with those kept on the ground. Another striking example is the decay of muons: these unstable particles, when moving close to the speed of light, survive far longer than their expected proper lifetime.

And so on.