Lorentz Transformations

The Lorentz transformations describe how the space-time coordinates of an event change when shifting from one inertial reference frame to another moving at a constant velocity in a straight line relative to the first.

These transformations lie at the heart of Einstein’s special relativity, because they ensure that the laws of physics-and in particular, the speed of light in a vacuum-remain the same in every inertial frame.

They apply strictly to inertial frames within the framework of relativity.

What is an inertial frame?

An inertial frame is a reference system in which Newton’s first law of motion holds: a free body, not acted upon by external forces, continues in uniform straight-line motion.

What does special relativity say?

Special relativity establishes that:

- no inertial frame has priority over another

- the laws of physics must take the same form in all inertial frames, whether at rest or in uniform motion

- the speed of light in a vacuum is constant and the same for all observers

This means that light does not require a stationary “medium” (the ether) to propagate, and that there is no universal fixed point against which absolute motion can be measured.

The Lorentz Transformation Equations

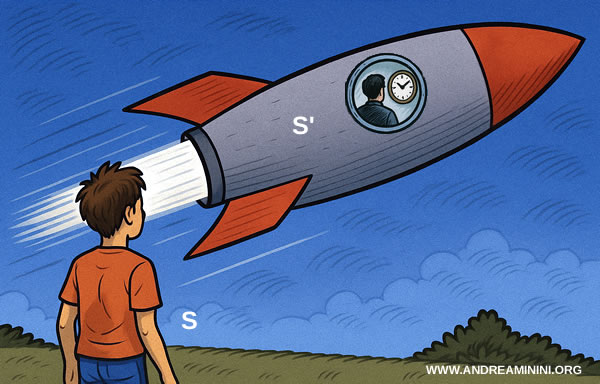

Consider two observers (or frames):

- $S$: the “stationary” reference frame

- $S'$: the frame moving at constant velocity $v$ along the $x$-axis

For simplicity, assume motion is confined to the $x$-axis, so the other spatial coordinates $y$ and $z$ remain unchanged.

An event occurring in frame $S$ with coordinates $(x, y, z, t)$ will have coordinates $(x', y', z', t')$ in frame $S'$ according to the Lorentz transformations:

$$

\begin{cases}

x' &= \gamma (x - vt) \\

y' &= y \\

z' &= z \\

t' &= \gamma \left(t - \frac{v}{c^2} x\right)

\end{cases}

$$

Here the Lorentz factor $ \gamma $ is defined as:

$$ \gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}}} $$

Notice that when $v$ is much smaller than $c$ ( $v \ll c$ ), the factor $\gamma \approx 1$, and the equations reduce to the familiar Galilean transformations.

What did Galileo propose? Galileo introduced the classical rules of motion we now call the “Galilean transformations.” These are valid only when the velocities involved are very small compared to the speed of light ($v \ll c$). According to Galilean transformations, if a frame $S'$ moves at constant velocity $v$ along the $x$-axis relative to a frame $S$, then the coordinates of an event transform as: $$ \begin{cases} x' &= x - vt \\ y' &= y \\ z' &= z \\ t' &= t \end{cases} $$ In this view, space changes with relative motion-the coordinate $x'$ reflects the system’s displacement-while time is the same for everyone: $t' = t$ is absolute, unaffected by the frame of reference. In short, Galileo argued that time flows uniformly for all observers and that velocities simply add together. This description works well at low speeds, but once velocities approach the speed of light, those rules break down and special relativity becomes essential.

Relativistic Effects

The Lorentz transformations lead to observable, experimentally confirmed consequences. The most important are outlined below.

- Relativity of simultaneity

Two events that occur at the same instant (simultaneous events) but at different positions in inertial frame $S$ will not, in general, be simultaneous in frame $S'$.

Events are simultaneous in both $S$ and $S'$ only if they occur at the same spatial point. Simultaneity, therefore, is not absolute but frame-dependent.Example. Two lightning bolts strike the ends of a moving train at the same time for an observer on the ground (frame $S$). A passenger seated at the midpoint of the train, however, does not perceive them as simultaneous.

In the train’s frame ($S'$), the passenger is in motion: the light from the front end approaches him, while the light from the rear must catch up. As a result, the flashes do not reach him at the same instant. This discrepancy is not an optical illusion but a concrete manifestation of the fact that simultaneity defined in $S$ (the ground observer) does not coincide with simultaneity in $S'$ (the passenger).Proof

Consider two inertial frames, $S$ and $S'$, with $S'$ moving at constant velocity $v$ along the $x$-axis relative to $S$. The Lorentz transformation for time is: $$ t' = \gamma \left( t - \frac{v}{c^2}x \right), $$ where $$ \gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - v^2/c^2}} $$ Suppose in $S$ two events $A$ and $B$ occur at different positions $x_A \neq x_B$ but at the same time: $$ t_A = t_B. $$ Since they are simultaneous $$ t_A - t_B = 0 $$ Applying the Lorentz transformation gives: $$ t'_A = \gamma \left( t_A - \frac{v}{c^2}x_A \right), \quad t'_B = \gamma \left( t_B - \frac{v}{c^2}x_B \right) $$ Subtracting, $$ t'_A - t'_B = \gamma \left( t_A - \frac{v}{c^2}x_A \right) - \gamma \left( t_B - \frac{v}{c^2}x_B \right) $$ $$ t'_A - t'_B = \gamma t_A - \gamma \frac{v}{c^2}x_A - \gamma t_B + \gamma \frac{v}{c^2}x_B $$ Since $t_A = t_B$, the terms in $\gamma t$ cancel: $$ \require{cancel} t'_A - t'_B = \cancel{\gamma t_A} - \gamma \frac{v}{c^2}x_A - \cancel{\gamma t_B} + \gamma \frac{v}{c^2}x_B $$ $$ t'_A - t'_B = \gamma \frac{v}{c^2}(x_B - x_A) $$ Thus the time difference $ t'_A - t'_B $ in $S'$ is proportional to the spatial separation $ x_B - x_A $ in $S$. Events that are simultaneous in $S$ but occur at different locations are not simultaneous in $S'$. Simultaneity is preserved across both frames only when the events occur at the same point in space ($x_A = x_B$). - Length contraction

An object has a proper length $L' $ in the frame $S' $, where it is at rest. If $S' $ moves relative to another inertial frame $S$, then from the standpoint of an observer in $S$, the object’s length appears shortened along the direction of motion: $$ L = \frac{L'}{\gamma} $$ The contraction affects only the dimension parallel to the motion. All transverse dimensions remain unchanged.

Example. A rod 2 meters long at rest in $S'$ appears just 1.2 meters long to an observer in $S$ when $S'$ moves at $0.8c$. $$ \gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - 0.8^2}} = \frac{1}{0.6} = 1.666... $$ $$

L = \frac{2}{1.666...} \approx 1.2 \text{ meters} $$ The same is true for a missile moving at nearly the speed of light: as seen by an observer, it looks shorter along its path of motion, while its width and height stay the same.

For instance, if a missile travels to the right along the $x$-axis, its height remains unchanged ($y = y'$), while its length appears shortened ($x' < x$) due to length contraction.

Demonstration of Length Contraction

Consider a rigid rod with proper length $L'$, lying along the $x'$ axis in its rest frame $S'$.

The endpoints in this frame have coordinates:

$$ x'_A = 0, \qquad x'_B = L' $$

In $S'$, the distance between the two ends, measured at any instant $t'$, is simply

$$ L' = x'_B - x'_A $$

Now let’s look at the same rod from another inertial frame $S$, where the rod is moving with velocity $v$ along the $x$ axis.

To measure its length in $S$, we must record the positions of both ends at the same instant $t$ according to the clocks in $S$.

The Lorentz transformations relate the coordinates in the two frames:

$$ x' = \gamma (x - vt), \qquad t' = \gamma \left(t - \frac{v}{c^2}x\right) $$

with the Lorentz factor defined as

$$ \gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - v^2/c^2}} $$

For endpoint $A$, located at $x'_A = 0$:

$$ x'_A = 0 = \gamma (x_A - vt) $$

$$ \frac{0}{\gamma} = x_A - vt $$

$$ x_A - vt = 0 $$

$$ x_A = vt $$

For endpoint $B$, located at $x'_B = L'$:

$$ x'_B = L' = \gamma (x_B - vt) $$

$$ \frac{L'}{\gamma} = x_B - vt $$

$$ x_B = vt + \frac{L'}{\gamma} $$

Since in frame $S$ both endpoints must be observed at the same time $t$, the measured distance is

$$ L = x_B - x_A = \left(vt + \frac{L'}{\gamma}\right) - (vt) = \frac{L'}{\gamma} $$

So in $S$, the rod’s length comes out shorter than its proper length $L'$, reduced by a factor of $\gamma$.

$$ L = x_B - x_A = \frac{L'}{\gamma} $$

In other words, an object in motion appears contracted along the direction of travel:

$$ L = \frac{L'}{\gamma} $$

This makes clear that length contraction is not a physical squeezing of the object, but an unavoidable consequence of the spacetime transformation linking inertial frames.

Note. Keep in mind that this contraction affects only the direction of motion. Dimensions perpendicular to the velocity-along $y$ or $z$, for example-remain unchanged, since the Lorentz transformations leave the transverse spatial coordinates untouched.

- Time Dilation

A proper time interval $T′$ is the duration measured in the frame $S′$, where the clock is at rest (that is, where it’s physically located). If the frame $S′$ is moving relative to another frame $S$, then, from the standpoint of an observer in $S$, time in $S′$ runs more slowly: $$ T = \gamma T' $$Example. A clock measures $1$ second ($T'=1s$) in its own frame $ S' $ (a spaceship) traveling at 90% of the speed of light ($v=0.9c$). To an observer watching the spaceship from a slower inertial frame $ S $, the clock on board $ S' $ appears to tick more slowly. $$ \gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-(0.9)^2}} \approx 2.29 $$ $$ T = \gamma T' \approx 2.29 \ s $$ In other words, the outside observer sees the hands of the spaceship’s clock moving in slow motion.

Deriving Time Dilation

Let’s look at a clock in a frame $ S' $, for example a moving spaceship or even a particle.

The time interval $ T' $ between two "ticks" of the clock (say, one second) is called the "proper time." In this case, the two events are simply the two ticks of the clock.

$$ T' = t'_B - t'_A $$

For someone traveling inside frame $ S' $, the clock is mounted on the wall. So, both ticks happen at the same place (the origin), separated by the time interval $T'$.

- The first tick $t'_A=0$ at position $ x'_A=0$

- The second tick $t'_B=T'$ at position $ x'_B=0$

Now imagine someone in a slower inertial frame $S$, say on Earth, watching $ S' $ (the spaceship) flying past at high speed $v$. How do they see the clock on $ S' $ ticking? To answer that, we apply the Lorentz transformation for time:

$$ t = \gamma \left(t' + \frac{v}{c^2}x'\right), \qquad \gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-v^2/c^2}}. $$

Let’s compute the times of the two ticks as seen in frame $S$:

- First tick: $t_A = \gamma (0 + \frac{v}{c^2}\cdot 0) = 0$

- Second tick: $t_B = \gamma (T' + \frac{v}{c^2}\cdot 0) = \gamma T'$

The time interval between the two ticks in $S$ is therefore

$$ T = t_B - t_A = \gamma T' $$

Since $\gamma \geq 1$, it’s always greater than one, which means $T \geq T'$. Put simply: in frame $ S $ (Earth), where the clock is moving along with the spaceship, the interval between ticks lasts longer, $T=\gamma T'$.

This shows that the passage of time slows down in any moving frame.

- Relativistic Addition of Velocities

In special relativity, velocities don’t simply add up linearly as they do in classical mechanics. If an object moves with velocity \(u'\) relative to a frame \(S'\), and that frame itself moves with velocity \(v\) relative to another frame \(S\), then the object’s velocity measured in \(S\) is not \(u = u' + v\). Instead, it follows the relativistic law: $$ u = \frac{u' + v}{1 + \tfrac{u'v}{c^2}} $$ The denominator ensures that the result never exceeds \(c\), even when combining very high speeds. For instance, if in frame \(S'\) an object moves at the speed of light (\(u' = c\)), then in every other inertial frame its velocity is still \(u = c\). This formula guarantees the invariance of the speed of light and makes clear that the Galilean rule \(u = u' + v\) holds only when velocities are much smaller than the speed of light \( v \ll c\).

Example. If a bullet travels at $u' = 0.9c$ on a train moving at $v = 0.5c$, its speed relative to the ground is not $1.4c$, but: $$ u = \frac{0.9c + 0.5c}{1 + \frac{0.9 \cdot 0.5}{1}} = \frac{1.4c}{1 + 0.45} = \frac{1.4c}{1.45} \approx 0.9655c $$

Proof

In classical mechanics, velocities combine according to the Galilean rule: if an object moves with velocity \( u' \) relative to a frame \( S' \), and this frame moves with velocity \( v \) relative to a frame \( S \), the object’s velocity relative to \( S \) is simply

$$ u = u' + v $$But this rule is inconsistent with special relativity, because it would break the invariance of the speed of light. For example, if an object in \( S' \) were moving at the speed of light \( c \), then using the classical sum would give:

$$ u = c + v > c $$This contradicts Einstein’s postulate that the speed of light is the same constant \( c \) in all inertial frames. Lorentz transformations, however, provide the correct velocity addition formula.

Consider a particle moving along the \( x \)-axis with velocity \( u' \) in frame \( S' \). Its displacement satisfies

$$ u' = \frac{\Delta x'}{\Delta t'} $$From the perspective of frame \( S \), the Lorentz transformations for spatial and temporal intervals are

$$ \Delta x = \gamma (\Delta x' + v \Delta t'), $$ $$ \Delta t = \gamma \left( \Delta t' + \frac{v}{c^2}\Delta x' \right) $$Thus, the velocity in frame \( S \) is:

$$ u = \frac{\Delta x}{\Delta t} = \frac{ \gamma (\Delta x' + v \Delta t')}{ \gamma ( \Delta t' + \tfrac{v}{c^2}\Delta x' )} = \frac{\Delta x' + v \Delta t'}{\Delta t' + \tfrac{v}{c^2}\Delta x'} $$Dividing numerator and denominator by $ \Delta t' $ and recalling that $ u'=\Delta x'/\Delta t' $, we get:

$$ u = \frac{ \frac{ \Delta x' + v \Delta t' }{ \Delta t' } }{ \frac{ \Delta t' + \tfrac{v}{c^2}\Delta x' }{ \Delta t' } } = \frac{\dfrac{\Delta x'}{\Delta t'}+v}{1+\dfrac{v}{c^2}\dfrac{\Delta x'}{\Delta t'}} = \frac{u' + v}{1 + \tfrac{u'v}{c^2}} $$

This relativistic velocity addition law preserves the speed of light as an absolute upper bound, setting an insurmountable limit on all dynamical processes.

$$ u = \frac{u' + v}{1 + \tfrac{u'v}{c^2}} $$

In fact, if \( u' = c \), then \( u = c \) regardless of the value of \( v \). Likewise, if both velocities are below \( c \), their combination always remains below \( c \).

$$ u = \frac{c + v}{1 + \tfrac{cv}{c^2}} = \frac{c + v}{1 + \tfrac{v}{c}} = \frac{c + v}{1 + \tfrac{v}{c}} \cdot \frac{c}{c} = \frac{c(c + v)}{c + v} = c$$

From this it follows that the speed of light is a universal constant that cannot be surpassed by adding relative motions.

Note. In the classical limit \( v \ll c \) and \( u' \ll c \), the denominator approaches unity $ 1 + \tfrac{u'v}{c^2} \approx 1 $, and the relativistic formula reduces to the Galilean rule \( u \simeq u' + v \). $$ u = \frac{u' + v}{1 + \tfrac{u'v}{c^2}} = \frac{u' + v}{1 + 0 } = u'+v $$ This shows that the Lorentz formula is fully consistent with classical mechanics in the non-relativistic regime.

Geometry of Space-Time

Special relativity doesn’t view space and time as separate, independent entities, but as parts of a single geometric framework known as space-time.

Every event-something that occurs at a specific place and moment - is described by four coordinates: the three spatial ones \( (x,y,z) \) plus the time coordinate multiplied by the speed of light ( ct ). Together, these form a four-vector $(x, y, z, ct)$.

Lorentz transformations preserve a particular quantity called the space-time interval:

\[ s^2 = c^2 t^2 - x^2 - y^2 - z^2 \]

This interval plays in space-time the same role that Euclidean distance plays in ordinary space. Just as distance remains unchanged under three-dimensional rotations, the space-time interval remains unchanged under Lorentz transformations-it is an invariant.

In essence, Lorentz transformations overturned the classical notion of time and space by eliminating any concept of absolutes.

They provide the mathematical and conceptual foundation of special relativity and are indispensable for making sense of high-velocity phenomena such as particle physics, relativistic electrodynamics, and cosmology.

And so on.