Structure of the Atom

An atom consists of two main parts: a central nucleus carrying a positive electric charge, and negatively charged particles orbiting around it.

The nucleus itself contains two types of particles: protons, which are positively charged, and neutrons, which carry no charge at all.

Orbiting the nucleus are electrons, tiny particles with a negative charge.

To get a sense of scale: the nucleus is minuscule compared with the whole atom, occupying only a tiny fraction of its size once the electron orbits are taken into account.

This means that most of an atom is essentially… empty space.

Note. Including the electron orbits, an atom measures about 10-10 meters across. The nucleus, by contrast, is only about 10-15 meters. In other words, the nucleus is ten thousand times smaller than the atom. A good analogy is placing a marble in the middle of a soccer field: the marble represents the nucleus, while the field - with all its emptiness - represents the atom, the space where the electrons orbit.

How many protons, neutrons, and electrons does an atom have?

In a neutral atom, the number of protons is equal to the number of electrons.

When these numbers match, the positive charge of the protons is perfectly balanced by the negative charge of the electrons.

The number of protons is called the atomic number, represented by the letter Z. It is fundamental because it defines the chemical element.

Example. A hydrogen atom is the lightest and most abundant element in the universe, found in water and in stars. It always has one proton, so its atomic number is Z=1. Carbon always has 6 protons, so Z=6. Oxygen always has 8 protons, giving it Z=8, and so on.

The atomic number (Z) should not be confused with the mass number (A), which is the sum of protons (Z) and neutrons (N) in the atom.

A = Z + N

Example. Carbon always has Z = 6 protons, but it can have either 6 neutrons (A = 12, carbon-12) or 7 neutrons (A = 13, carbon-13). In both cases, it remains carbon.

The case of ions

When the number of protons equals the number of electrons, the charges cancel and the atom is neutral. But if this balance is lost, the atom becomes an ion.

- Positive ion (cation): formed when there are more protons than electrons

- Negative ion (anion): formed when there are more electrons than protons

Example. A sodium atom ($Na$) has 11 electrons when neutral, because its atomic number Z is 11 (meaning 11 protons and therefore 11 electrons). Its electron configuration is: $$ 1s^2 \; 2s^2 \; 2p^6 \; 3s^1 $$ So it has 2 electrons in the first shell, 8 in the second, and just 1 in the third (the outer shell). That single outer electron is very easy to lose, which is why sodium readily forms the positive ion $Na^+$. This is also why it bonds so easily with a chlorine ion ($Cl^-$) to form sodium chloride $Na^+Cl^-$ - better known as table salt.

Here’s another example. Oxygen ($O$), with Z = 8, has 8 protons and 8 electrons when neutral. But it tends to capture two additional electrons to complete its octet and become stable, forming the oxide ion ($O^{-2}$). In its second energy level ($n=2$), two of the eight available slots are unfilled. Completing this “octet” makes the atom more stable, which is why oxygen tends to pick up two electrons and become a negative ion.

And what about neutrons?

To find out how many neutrons (N) an atom has, you need to know its atomic number (Z) and its mass number (A).

N = A - Z

So the number of neutrons is simply the difference between the mass number and the atomic number.

The number of neutrons does not determine the identity of the element - that depends only on the number of protons, or the atomic number Z.

Neutrons, however, do affect the mass of the atom and are at the heart of the phenomenon of isotopes.

What is an isotope? Isotopes are atoms of the same chemical element - meaning they have the same atomic number Z (the number of protons) - but differ in the number of neutrons (N), and therefore in mass. Put simply, isotopes are different forms of the same element: they share the same atomic number but have different atomic masses. The term "isotope" comes from the fact that they occupy the same position as the element in the periodic table. For instance, hydrogen (H) in its most common form has one proton and one electron, but no neutrons. Hydrogen can also appear as deuterium, with one proton, one electron, and one neutron, or as tritium, with one proton, one electron, and two neutrons. All three are isotopes of hydrogen.

Because neutrons have no electric charge, they do not affect the atom’s overall electrical state.

What they do affect, however, is something else entirely: the stability of the nucleus.

An atom is considered stable when its nucleus does not spontaneously transform into another nucleus.

But not all nuclei are stable: some are unstable and eventually decay, releasing radiation as they transform into more stable forms.

This nuclear instability is precisely what gives rise to phenomena such as radioactivity.

Example. Carbon-12 has 6 protons and 6 neutrons and is stable and forms the essential basis of life.

By contrast, Carbon-14 is an unstable isotope that decays slowly and is widely used to date archaeological and organic remains up to about 50,000 years old. Carbon-14 has 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Over time it undergoes beta decay ( $ β^- $ ): $$ {}^{14}_6 C \;\;\longrightarrow\;\; {}^{14}_7 N \;+\; e^- \;+\; \bar{\nu}_e $$ In simple terms, one neutron in the carbon nucleus turns into a proton, emitting an electron (a beta-minus particle) and an electron antineutrino. The nucleus then becomes nitrogen-14 ($N$), which is stable.

The arrangement of electrons

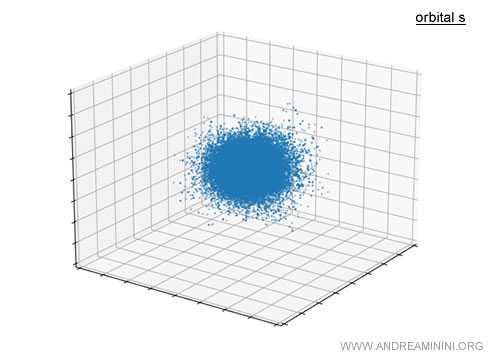

Electrons do not wander randomly around the nucleus: they occupy quantized regions called orbitals. Each orbital represents a “probability cloud” where the electron is most likely to be found.

An orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons, one with spin up and the other with spin down, in accordance with the Pauli exclusion principle.

Atomic orbitals fall into four main categories:

- s (spherical)

- p (two-lobed)

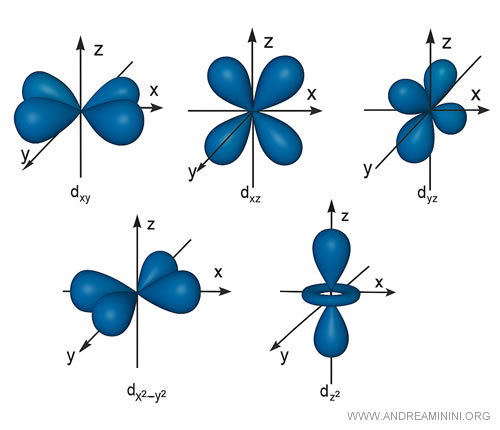

- d (more complex, often four or five lobes)

- f (even more elaborate)

For example, the s orbital is roughly spherical around the nucleus.

Strictly speaking, it isn’t a solid sphere but a cloud of probability showing where the electron is most likely to be found.

p orbitals, by contrast, are elongated along three axes: $p_x$, $p_y$, and $p_z$.

Each p orbital can accommodate up to two electrons.

As the energy level increases, the number of orbitals grows, and their shapes become progressively more complex.

d orbitals, for instance, generally display four-lobed structures, with one exception of a different shape.

Again, each orbital can hold no more than two electrons.

Example. The first energy level $n=1$ contains only a single s orbital, so it can hold a maximum of 2 electrons. The second level $n=2$ includes one s orbital and three p orbitals, giving a total of four orbitals and up to 8 electrons - the basis of what chemistry calls the “octet rule.”

The third energy level $n=3$ consists of one s orbital, three p orbitals, and five d orbitals - 9 orbitals in total, for a maximum of 18 electrons, and so on. Here you can see the s, p, d, and f orbitals across the first seven energy levels.

Notice that the filling order doesn’t always follow the sequence of principal quantum numbers $n$. Electrons always occupy the lowest-energy orbitals first before moving to higher ones (this is the “aufbau principle,” from the German word for “building up”). For example, after the $3p$ orbitals are filled, electrons enter the $4s$ orbital - slightly lower in energy than $3d$ - even though $4s$ belongs to a higher energy level ($n=4$). Only afterward do they fill the $3d$ orbitals. In short: the filling order follows increasing orbital energy $E$, not simply the level number $n$.

This electron arrangement is what ultimately determines the chemical properties of each element.

And beyond this, the pattern continues.