Hadrons

Hadrons are subatomic particles composed of quarks bound together by the strong nuclear force, carried by gluons.

They are not elementary particles, as they contain quarks and, in some cases, antiquarks.

The term “hadron” comes from the Greek hadrós, meaning “stout” or “massive,” a nod to their relatively large mass compared with, for example, leptons.

Note. This is not an absolute rule - some hadrons are quite light. The pion, for instance, is less massive than the proton.

According to their internal structure, hadrons are traditionally grouped into three main categories:

- Baryons

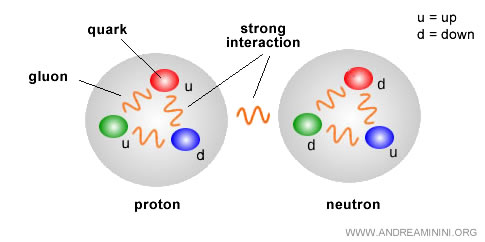

Baryons are made of three quarks (or, for antibaryons, three antiquarks). The two most familiar examples are the proton (uud: two up quarks and one down quark) and the neutron (udd: two down quarks and one up quark). Because they have half-integer spin (1/2 or 3/2), baryons are fermions and obey Fermi - Dirac statistics.

Note. The proton is the only known baryon stable in isolation. A free neutron, by contrast, survives on average about 15 minutes before decaying into a proton, an electron, and an electron antineutrino. All other baryons are unstable and decay over comparatively short timescales.

- Mesons

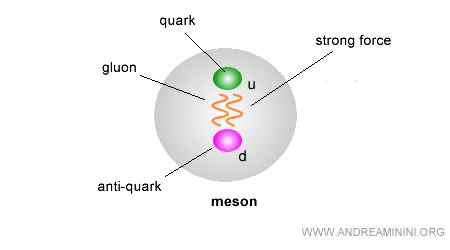

Mesons consist of one quark paired with one antiquark. The quark and antiquark carry opposite color charges - one a color, the other the matching anticolor (for example, green and anti-green) - forming a color-neutral system. Common examples include pions and kaons. The combined spins of the quark and antiquark result in an integer value (0 or 1), which makes mesons bosons that follow Bose - Einstein statistics.

Note. No meson is stable. All decay, with lifetimes ranging from fractions of a second to fractions of a femtosecond. Some have relatively “long” lifetimes on a subatomic scale, but all are ultimately unstable.

- Exotic hadrons

More complex configurations, known as exotic hadrons, do not fit into the standard baryon/meson classification. Examples include tetraquarks (two quarks and two antiquarks) and pentaquarks (four quarks and one antiquark). These states were predicted decades ago and have only recently been observed experimentally at CERN and other research facilities.

Broadly speaking, hadrons include all particles that experience the strong interaction and are built from quarks bound in various arrangements.

We now know there are six fundamental quark “flavors,” and every hadron is composed of some combination of these.

Note. Over the decades, physicists have identified a vast array of hadrons, each with its own combination of charge, mass, and spin. None are truly “fundamental”: all are made from quarks bound together in different ways. In the 1950s and 1960s, the explosion of newly discovered hadrons prompted the search for a simpler organizing principle - a framework that could explain them as different combinations of a small set of basic constituents. This led to the quark model, with new quark flavors introduced to account for hadronic properties: first the strange quark, then charm, and so on.

And the exploration of hadronic matter continues…