Quantum Chromodynamics

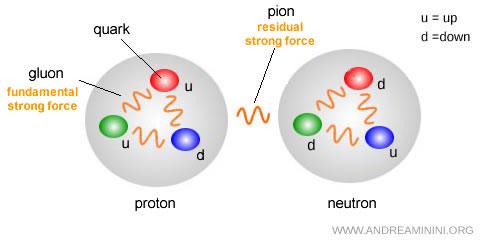

Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), or cromodinamica quantistica, is the branch of physics that describes the strong force - the fundamental interaction that binds protons and neutrons within the atomic nucleus and, more fundamentally, holds quarks together to form particles called hadrons.

QCD explains why quarks can never exist in isolation and why they instead combine to form the particles that make up the building blocks of matter.

In short, QCD plays the same role for the strong force that quantum electrodynamics (QED) plays for electromagnetism.

Note. The strong force is one of the four fundamental forces of nature, alongside gravity, electromagnetism, and the weak interaction.

Just as QED is based on electric charge, QCD introduces a new kind of charge: color.

Quarks come in three types of color charge: red, green, and blue.

All observable particles in nature (protons, neutrons, mesons) are color-neutral, meaning they are made of combinations that cancel out color:

- Baryons

Composed of three quarks, one of each color (red, green, blue). No two quarks in a baryon share the same color. - Mesons

Made of a quark and an antiquark, i.e., a color paired with its anticolor. The pair need not be identical (for example, blue and anti-red).

The strong force is carried by gluons, elementary particles.

The exchange of virtual gluons is depicted by a wavy line labeled $g$ on the internal lines of Feynman diagrams.

A quark ($q$) may:

- emit a virtual gluon $ q \;\rightarrow\; q + g $

- absorb a virtual gluon $ q + g \;\rightarrow\; q $

In quantum chromodynamics, the strong force that confines two quarks within a hadron (such as a proton or neutron) is modeled as the exchange of gluons between them.

Gluons are analogous to photons in electromagnetism, but with one crucial distinction: photons are electrically neutral, whereas gluons themselves carry color charge.

This means that gluons interact with one another, making QCD far richer and more complex than QED.

In Feynman diagrams, gluon self-interactions appear as either three-gluon vertices (g - g - g) or four-gluon vertices (g - g - g - g).

In particular, since gluons themselves carry color charge, they can also alter the color of quarks.

As an example, a red quark can change into a blue quark by emitting a red - antiblue gluon. The gluon, in turn, carries away the corresponding difference in color charge.

The gluon includes a red component that cancels the quark’s initial color, together with an antiblue component that accounts for the new color acquired. This ensures the overall conservation of color charge.

Note. Quarks can change color, but not flavor. For instance, a red up quark may shift to blue, yet it can never become a down quark - regardless of color.

There are eight distinct gluons ($g_1, g_2, \dots, g_8$), but only six of them actively mediate color exchange between quarks.

| Gluon | Unnormalized Combination | Normalized Combination | Color Transition |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( g_1 \) | \( r\bar{g} + g\bar{r} \) | \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(r\bar{g} + g\bar{r}) \) | Red ⇌ Green |

| \( g_2 \) | \( r\bar{g} - g\bar{r} \) | \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(r\bar{g} - g\bar{r}) \) | Red ⇌ Green |

| \( g_3 \) | \( r\bar{r} - g\bar{g} \) | \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(r\bar{r} - g\bar{g}) \) | No exchange |

| \( g_4 \) | \( r\bar{b} + b\bar{r} \) | \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(r\bar{b} + b\bar{r}) \) | Red ⇌ Blue |

| \( g_5 \) | \( r\bar{b} - b\bar{r} \) | \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(r\bar{b} - b\bar{r}) \) | Red ⇌ Blue |

| \( g_6 \) | \( g\bar{b} + b\bar{g} \) | \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(g\bar{b} + b\bar{g}) \) | Green ⇌ Blue |

| \( g_7 \) | \( g\bar{b} - b\bar{g} \) | \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(g\bar{b} - b\bar{g}) \) | Green ⇌ Blue |

| \( g_8 \) | \( r\bar{r} + g\bar{g} - 2b\bar{b} \) | \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}(r\bar{r} + g\bar{g} - 2b\bar{b}) \) | No exchange |

For example, gluons $g_1$ and $g_2$ both mediate color exchange between red and green quarks, yet they are not identical: $g_1$ is the symmetric, real superposition of $r\bar{g}$ and $g\bar{r}$, whereas $g_2$ is the antisymmetric, imaginary one. Both drive the $r \leftrightarrow g$ transition, but they correspond to distinct components of the color field.

The remaining two gluons, $ g_3 $ and $ g_8 $, do not change color directly, but they still play an essential role in the dynamics of the non-Abelian color field.

Color exchange can be visualized schematically as follows:

Note. QCD is a cornerstone of the Standard Model of particle physics. It has been vital in explaining the stability of matter, the structure of atomic nuclei, and the outcomes of high-energy scattering experiments.

Asymptotic Freedom

One of QCD’s most remarkable results is the discovery of asymptotic freedom.

At very short distances (such as inside a proton), the strong force weakens: quarks move almost as though they were free.

At larger distances, however, the interaction grows progressively stronger.

This property explains why, in high-energy collisions such as those at particle accelerators, quarks appear nearly independent.

Quark Confinement

The flip side of asymptotic freedom is confinement: quarks are never found alone in nature.

If one tries to pull them apart, the energy stored in the “string” of gluons between them increases without bound.

Eventually, it becomes energetically favorable to create a new quark - antiquark pair, so instead of isolating a single quark, new bound states are produced.

This explains why free quarks have never been observed: they exist only within mesons and baryons.

Note. Despite its successes, QCD still presents major challenges - above all, a rigorous mathematical proof of confinement remains one of the deepest unsolved problems in theoretical physics.

How QCD Differs from QED

Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD) is closely related to Quantum Electrodynamics (QED), yet the two differ in essential ways.

| Aspect | QED (Quantum Electrodynamics) | QCD (Quantum Chromodynamics) |

|---|---|---|

| Charge | Electric charge (+ / -) | Color (red, green, blue) |

| Mediator | Photon (neutral) | Gluon (carries color) |

| Interactions among mediators | No | Yes, gluons interact with one another |

| Coupling constant | Small and fixed (α ≈ 1/137) | Large and variable (depends on distance) |

| Free particles | Electrons, protons | No free quarks (confinement) |

| Characteristic phenomenon | Charge screening: charge appears weaker at long range | Anti-screening: charge appears stronger at long range (asymptotic freedom) |

In particular, while QED deals with a single type of charge (positive or negative), QCD introduces the richer concept of color (red, green, and blue).

And unlike photons, which are neutral and do not interact with each other, gluons carry color charge and therefore interact among themselves.

What do “screening” and “anti-screening” mean?

To highlight the difference, let’s look more closely at what screening involves.

- Screening in QED

In quantum electrodynamics (QED), the vacuum becomes polarized, leading to the appearance of electron - positron pairs. They are often depicted using Feynman diagrams.

So, an electric charge (say, an electron) is surrounded by virtual electron - positron pairs. The virtual electrons (negative) are pulled toward a positive charge, while the positrons are pushed away. This creates a cloud of opposite charge that weakens the field at long distances. As a result, the charge appears smaller when viewed from afar - this is “screening.”Example. In QED, the quantum vacuum behaves like a dielectric medium: quantum fluctuations give rise to polarization effects due to virtual electron - positron pairs. Around a negative charge $q$, the vacuum polarizes in a way that reduces the electric field at large distances. The effective charge $q_e(r)$ measured far away is therefore smaller than the bare charge.

The same occurs for a positive charge: vacuum polarization reduces its long-range influence. This phenomenon, known as vacuum screening, means that the electromagnetic coupling (the effective charge) increases at shorter distances.

- Anti-screening in QCD

In quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the vacuum seethes with quantum fluctuations: virtual quark - antiquark pairs continually flicker in and out of existence, while virtual gluons can even interact directly with one another. The theory specifically predicts self-interaction vertices involving three gluons (g - g - g) and four gluons (g - g - g - g). Unlike photons in quantum electrodynamics (QED), gluons themselves carry color charge, which enables them to interact with each other.

The quark - gluon interaction (q - g) tends to promote quark - antiquark pairing at short distances (and, in some cases, quark - quark pairing). By contrast, gluon self-interactions (g - g - g), made possible by their own color charge, drive the opposite effect. The effective strength of QCD is described by a coupling constant that is not fixed but varies with distance, depending on the sign of the parameter $ \alpha $. If $\alpha$ is positive, the coupling grows at short range; if negative, it weakens. $$ \alpha = 2f - 11n $$ Here $f = 6$ corresponds to the quark flavors and $n = 3$ to the colors. In QCD the parameter is negative, $\alpha = -21$, meaning the coupling decreases at short distances: this is the phenomenon of asymptotic freedom, whereby quarks inside hadrons behave almost as free particles. The same property also gives rise to anti-screening: quantum fluctuations of virtual gluons enhance the color interaction (or effective color charge $ q_e $) as the separation $ r $ increases, rather than diminishing it as in QED with vacuum screening.

The outcome is that the strong coupling constant $ \alpha_s $ grows with distance. At very short scales, such as in high-energy collisions, the interaction weakens and quarks act almost like free particles (asymptotic freedom). At larger scales, however, the interaction intensifies (anti-screening), ensuring that quarks can never be isolated: they remain permanently confined within hadrons (quark confinement).

And so forth.