Neutrinos

The neutrino, denoted by the Greek letter $\nu$, is an elementary particle belonging to the leptons family. It carries no electric charge, has an extraordinarily small rest mass (far smaller than that of any other particle with a nonzero mass), and a spin of $1/2$, classifying it as a fermion.

These properties make it an almost “ghost-like” particle: immune to the electromagnetic force, unaffected by the strong nuclear force, and able to pass through matter virtually unhindered.

Neutrinos interact solely via the weak nuclear force and gravity - the latter being negligible because of their minuscule mass.

They are produced in a wide variety of natural and artificial processes: during beta decay of atomic nuclei and hadrons, in nuclear fusion inside stars (including our Sun), in nuclear reactors, in cosmic ray collisions with Earth’s atmosphere, and in particle accelerators.

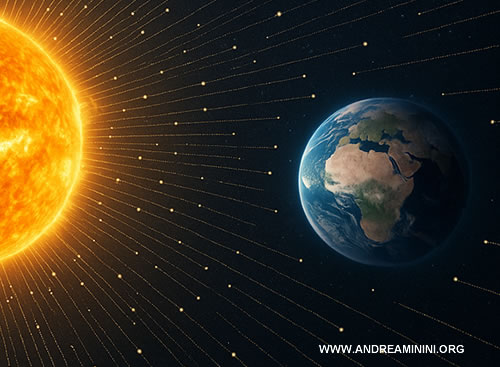

Note. Their penetrating power is astonishing: every second, billions of neutrinos from the Sun stream through each square centimeter of Earth without being stopped. In the Sun’s core, nuclear fusion transforms hydrogen into helium, releasing vast numbers of electron neutrinos; roughly $ 6.5 \times 10^{10} \ \text{neutrinos} / (\text{cm}^2 \cdot \text{s}) $ reach Earth’s surface - meaning tens of billions pass through an area no larger than a fingernail every second, without any perceptible effect.

Why they’re called neutrinos

The name reflects their neutral electric charge and draws a parallel to the neutron - a larger, more massive nucleon found in the atomic nucleus.

Like the neutrino, the neutron carries no positive or negative electric charge.

How neutrinos differ from neutrons

The neutron is vastly heavier and interacts through the strong nuclear force, whereas the neutrino interacts only via the weak force.

The precise mass of the neutrino remains unknown. Some estimates suggest it may be around a million times lighter than an electron.

Other estimates place it only tens of thousands of times lighter.

Note. If, hypothetically, a neutrino’s mass were a million times smaller than an electron’s, and given that an electron’s mass is 1835 times smaller than that of a neutron (see the atomic nucleus), a neutrino would be roughly two billion times lighter than a neutron.

Measuring the neutrino’s mass is a key challenge in astrophysics. The total mass of all neutrinos in the Universe could help explain, at least in part, the origin of dark matter.

Neutrino Properties

Below is a concise reference table summarizing the key physical characteristics of neutrinos.

| Property | Value / Description |

|---|---|

| Symbol | ν (neutrino), ν̄ (antineutrino) |

| Flavors (types) | νe, νμ, ντ |

| Lepton number | νe: Le=+1, νμ: Lμ=+1, ντ: Lτ=+1 Antineutrinos: corresponding flavors with lepton number -1 |

| Electric charge | 0 (electrically neutral) |

| Spin | ½ (fermions, obeying Fermi - Dirac statistics) |

| Rest mass | Nonzero but extremely small (« 1 eV/c2); only mass differences have been measured, not absolute values |

| Interactions | Weak force (mediated by W⊃± and Z0 bosons) and gravity (negligible at subatomic scales) |

| Helicity / Chirality | All observed neutrinos are left-handed; all observed antineutrinos are right-handed |

| Oscillations | Can change flavor as they travel (PMNS mixing) |

| Typical cross section | ∼10-44 m2 at MeV energies (increases with energy in this range) |

| Transparency to matter | Interact so rarely that they can pass through enormous amounts of matter without scattering |

The absolute masses of neutrinos remain unknown. Only upper bounds are available, as quoting specific values would be speculative.

Flavors, Antineutrinos, and Lepton Numbers

There are three “flavors” of neutrinos, each associated with a charged lepton from the same family:

| Neutrino flavor | Symbol | Associated lepton |

|---|---|---|

| Electron neutrino | \(\nu_e\) | Electron |

| Muon neutrino | \(\nu_{\mu}\) | Muon |

| Tau neutrino | \(\nu_{\tau}\) | Tau |

A neutrino created with a particular flavor does not necessarily retain that identity as it travels. This process is known as neutrino oscillation.

Every neutrino has a well-defined lepton number.

Each neutrino has a corresponding antiparticle, called an antineutrino, which carries the opposite lepton number.

| Particle | Symbol | Name | Lepton number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron neutrino | \(\nu_e\) | Electron neutrino | +1 |

| Muon neutrino | \(\nu_{\mu}\) | Muon neutrino | +1 |

| Tau neutrino | \(\nu_{\tau}\) | Tau neutrino | +1 |

| Electron antineutrino | \(\bar{\nu}_e\) | Electron antineutrino | -1 |

| Muon antineutrino | \(\bar{\nu}_{\mu}\) | Muon antineutrino | -1 |

| Tau antineutrino | \(\bar{\nu}_{\tau}\) | Tau antineutrino | -1 |

What is the lepton number? The lepton number is a quantum number assigned to every particle in the lepton family, used to keep track of leptons during reactions. In the Standard Model, the total lepton number is conserved - meaning the sum before and after a reaction must be identical. In general, the assignments are as follows:

- Leptons (electron, muon, tau, and their respective neutrinos) have lepton number $+1$.

- Antileptons (positron, antimuon, antitau, and antineutrinos) have lepton number $-1$.

- All other particles (quarks, photons, gluons, etc.) have lepton number $0$.

Neutrinos and antineutrinos are present in many nuclear processes, both in nature and in laboratory settings.

Example

In beta⁻ decay, a neutron in the nucleus transforms into a proton.

During this process, an electron and an electron antineutrino are emitted:

$$ n \rightarrow p + e^- + \bar{\nu}_e $$

On the left side of the equation, the neutron $n$ has a lepton number of $0$.

On the right, we have:

- a proton $p$ with lepton number $0$

- an electron $e^-$ with lepton number $+1$

- an electron antineutrino $\bar{\nu}_e$ with lepton number $-1$

The total lepton number on the right is:

$$ 0 + 1 + (-1) = 0 $$

Since the lepton number is $0$ on both sides, the total lepton number is conserved.

This means the reaction is allowed under the Standard Model.

Note. In beta⁺ decay, the reverse occurs: a proton transforms into a neutron. In this case, a positron (the electron’s antiparticle) and an electron neutrino are emitted: $$ p \rightarrow n + e^+ + \nu_e $$ Here as well, lepton number is conserved: $$ p^{(0)} \;\rightarrow\; n^{(0)} \;+\; e^{+\,(-1)} \;+\; \nu_e^{(+1)} $$ For clarity, the lepton number of each particle is shown as a superscript. The sum on both sides remains $0 + (-1) + (+1) = 0$. This reaction is likewise allowed by the Standard Model.

Why Neutrinos Pass Through Matter So Easily

Neutrinos slip through matter with astonishing ease because they interact only via the weakest of nature’s forces.

From a physics standpoint, their near “invisibility” comes down to three main factors:

- Weak interaction

Neutrinos have no electric charge, so they are completely unaffected by the electromagnetic force - no attraction to protons, no repulsion from electrons. They respond only to gravity (utterly negligible at subatomic scales) and the weak nuclear force, which is vastly weaker than both the strong nuclear force and electromagnetism. On top of that, the weak force acts over incredibly short ranges - roughly $10^{-18}$ meters - making the chance of a neutrino ever “hitting” a nucleon extraordinarily small. - Extremely small cross section

The likelihood of a particle interacting with another is described by its cross section ($\sigma$). For a typical neutrino ($E \approx 1\ \text{MeV}$), this is on the order of $10^{-44} \ \text{m}^2$ - billions of billions of times smaller than that of a charged particle. To put that into perspective, a neutrino could traverse several light-years of solid lead without a single interaction. - Minuscule mass

While not massless, neutrinos have an incredibly small mass (less than $1\ \text{eV}/c^2$). This allows them to move at speeds extremely close to that of light, giving them even less opportunity to interact - they simply don’t “linger” long enough near nucleons to react.For instance, here on Earth, about 60 billion neutrinos from the Sun pass through every square centimeter of matter each second - almost all without interacting at all.

These factors combined make the probability of a neutrino interacting with matter vanishingly small.

Historical Background

In 1930, Wolfgang Pauli realized that the process of beta decay appeared to violate the law of energy conservation.

Only part of the excess energy was released as a beta particle; the rest seemed to vanish into thin air - something that simply cannot happen according to the laws of physics.

To resolve this puzzle, Pauli proposed the existence of a new particle - electrically neutral, with an extremely small mass - that could carry away the missing energy in β decay.

Note. Pauli observed that a radioactive nucleus $ A $ could transform into a slightly lighter nucleus $ B $, emitting an electron $ e^- $: $$ A \rightarrow B + e^-$$ However, charge conservation implied that nucleus $B$ should have a greater positive charge than $A$, which was not supported by experimental data at the time. The neutron had not yet been discovered. Moreover, the emitted electron’s energy was consistently lower than predicted by energy conservation.

In 1934, Enrico Fermi built upon Pauli’s idea, formulating his theory of beta decay and coining the term “neutrino” to describe what he called the Pauli particle.

According to Fermi’s model, in beta decay a neutron transforms into a proton, an electron, and an electron antineutrino:

$$ n \rightarrow p^+ + e^- + \bar{\nu}_e $$

Note. The term “neutrino” was reportedly coined half in jest, as a diminutive of “neutron,” during a conversation between Enrico Fermi and Edoardo Amaldi at the Via Panisperna physics institute in Rome.

It was later established that there are two main kinds of neutrinos:

- The neutrino is produced in β⁺ decay, accompanying the emission of a positron e+. In β⁺ decay (beta plus), a proton within an unstable nucleus transforms into a neutron, emitting a positron and an electron neutrino: $$ p \;\longrightarrow\; n + e^+ + \nu_e $$ The reverse of β⁺ decay is the absorption of an electron antineutrino: $$\bar{\nu}_e + p \to n + e^+$$

Note. A free proton cannot undergo β⁺ decay because of energy conservation (a neutron is more massive than a proton), but it can occur within a nucleus where the nuclear mass difference compensates for the energy gap.

- The antineutrino is produced in β⁻ decay, accompanying the emission of an electron e-. In β⁻ decay (beta minus), a neutron - free or bound - transforms into a proton, emitting an electron and an electron antineutrino: $$ n \;\longrightarrow\; p + e^- + \bar{\nu}_e $$ The reverse of β⁻ decay is the absorption of an electron neutrino: $$\nu_e + n \to p + e^-$$

By 1949, it was also accepted that pions $ \pi^- $ decay into muons and neutrinos, and that muons $ \mu^- $ themselves decay into an electron ($ e $) and two neutrinos ($ 2 \nu $):

$$ \pi^- \rightarrow \mu^- + \nu $$

$$ \mu^- \rightarrow e^- + 2\nu $$

In 1953, Konopinski and Mahmoud introduced the principle of lepton number conservation in all particle interactions.

Note. Under this principle, $L = +1$ is assigned to all leptons (electron, muon, tau, and their respective neutrinos), $L = -1$ to all antileptons (positron, antimuon, antitau, and antineutrinos), and $L = 0$ to all other particles. A reaction can only proceed if the total lepton number before and after the interaction is the same.

By the early 1950s, the neutrino was widely accepted in theory, yet no direct experimental evidence existed - leading some to suspect it might be nothing more than a convenient mathematical construct.

The first definitive detection came in 1956, when Cowan and Reines observed the electron antineutrino via inverse beta decay:

$$ \bar{\nu} + p^+ \rightarrow n + e^+ $$

By the late 1950s, physicists began to ask whether neutrinos and antineutrinos might actually be the same particle, since both are electrically neutral.

In 1958, Raymond Davis provided experimental proof that neutrinos and antineutrinos are distinct particles, confirming earlier predictions from lepton number conservation.

Example. The following reaction is allowed because the sum of the lepton numbers (shown in superscript parentheses) is the same on both sides: $$\bar{\nu}^{(-1)} + p^{+(0)} \;\longrightarrow\; n^{(0)} + e^{+( -1 )} $$ By contrast, this reaction is forbidden because the total lepton number does not match: $$ \nu^{(+1)} + p^{+(0)} \;\longrightarrow\; n^{(0)} + e^{+( -1 )} $$ This highlights the fundamental distinction between neutrinos and antineutrinos.

In 1962, an experiment by Lederman, Schwartz, and Steinberger provided the first direct evidence for two distinct neutrino “flavors”: the electron neutrino and the muon neutrino.

Once neutrinos and antineutrinos - and their various flavors - were distinguished, pion decays could be written as:

$$ \pi^- \rightarrow \mu^- + \bar{\nu}_\mu $$

$$ \pi^+ \rightarrow \mu^+ + \nu_\mu $$

Muon decays take the form:

$$ \mu^- \rightarrow e^- + \bar{\nu}_e + \nu_\mu $$

$$ \mu^+ \rightarrow e^+ + \nu_e + \bar{\nu}_\mu $$

Neutrino Oscillation

Neutrino oscillation is a quantum phenomenon in which a neutrino (electron, muon, or tau) can change its flavor as it moves through space.

In practice, an electron neutrino can transform into a muon or a tau neutrino, and the reverse can also happen.

We currently know of three types (or flavors) of neutrinos:

- $ \nu_e $ (electron neutrino)

- $ \nu_{ \mu } $ (muon neutrino)

- $ \nu_{ \tau } $ (tau neutrino)

These neutrinos all have different masses-tiny, but definitely not zero.

The crucial point is that none of them corresponds to a single mass state. Instead, each is a quantum superposition of the three mass states \(\nu_1, \nu_2, \nu_3\), which have distinct masses \(m_1, m_2, m_3\).

$$ \begin{bmatrix} \nu_e \\ \nu_\mu \\ \nu_\tau \end{bmatrix} = U \begin{bmatrix} \nu_1 \\ \nu_2 \\ \nu_3 \end{bmatrix} $$

Here, \(U\) is the PMNS matrix (Pontecorvo-Maki-Nakagawa-Sakata), which encodes the mixing angles and phases.

This means that a neutrino created as \(\nu_e\) is actually a blend of the three mass states. As it propagates, each mass state evolves with a different phase. The mixture shifts over time, so the neutrino may later be detected as \(\nu_\mu\) or \(\nu_\tau\)-a flavor different from the one it started with.

Experiments have confirmed this behavior beyond doubt.

Note. This mechanism provided the solution to the long-standing “solar neutrino problem”: the puzzling shortfall in the number of solar electron neutrinos compared to theoretical predictions. The resolution is that many of them oscillate into muon or tau neutrinos on their journey from the Sun to Earth.

The very existence of oscillation proves that neutrinos must have nonzero mass-a striking discovery, since the original Standard Model assumed they were massless.

And so the story continues.