Mesons

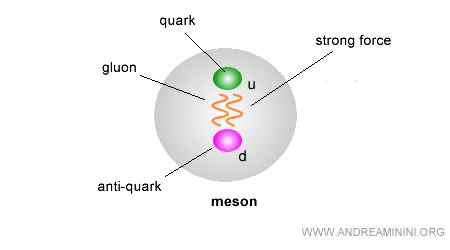

Mesons are subatomic particles made up of an equal number of quarks and antiquarks - most often a single $q\bar{q}$ pair - held together by the strong interaction.

They are composite rather than elementary particles and belong to the family of hadrons, along with baryons.

Because they have integer spin (0 or 1), mesons are bosons and obey Bose - Einstein statistics.

A meson is formed by the combination of:

- a quark (e.g., $u$, $d$, $s$, $c$, $b$, $t$)

- an antiquark (e.g., $\bar{u}$, $\bar{d}$, $\bar{s}$, $\bar{c}$, $\bar{b}$, $\bar{t}$)

The quark and antiquark can be of the same type (e.g., $c\bar{c}$) or of different types (e.g., $u\bar{d}$).

For example, the $\pi^+$ meson consists of a $u$ quark and a $\bar{d}$ antiquark. The $K^0$ meson contains a $d$ quark and a $\bar{s}$ antiquark. The $J/\psi$ meson is made of a $c$ (charm) quark and a $\bar{c}$ antiquark, and so on.

Although mesons can, in principle, include more complex quark - antiquark combinations (e.g., $cc\bar{c}\bar{c}$), by definition they are restricted to simple $q\bar{q}$ systems.

States containing four quarks (tetraquarks) are generally considered “exotic.”

Mesons are unstable and decay quickly into other particles - such as photons, electrons, muons, or neutrinos - depending on the type.

Lighter mesons generally have longer lifetimes and are more easily observed in cosmic rays.

For instance, the neutral pion $\pi^0$ decays into two photons $\gamma$, while the charged kaon $K^+$ can decay into a muon $\mu^+$ and a neutrino $\nu_\mu$.

Why “meson”?

The term “meson” comes from the Greek “mesos,” meaning “middle,” chosen because their masses were originally thought to lie between that of the light electron and the heavier proton.

Note. In 1935, Japanese physicist Hideki Yukawa predicted the existence of a particle that would mediate the strong force - a meson with a mass between that of the electron and the proton. In 1947, the first meson was detected experimentally: the pion $\pi$.

Today, mass alone is no longer a defining criterion for mesons, although the name has persisted for historical reasons.

In fact, many mesons are now known to have masses greater than that of the proton.

Likewise, there are other particles - such as heavy leptons (muon and tau) - that fall between the electron and proton in mass but are not mesons, since they are not made of quarks.

In short, not all mesons have masses between those of the electron and proton, and not all particles in that range are mesons.

The role of mesons in fundamental interactions

Although they are composite, mesons can act - at certain scales - as effective carriers of the strong force between protons and neutrons in atomic nuclei.

The lightest mesons, especially pions ($\pi^+$, $\pi^-$, $\pi^0$), play a crucial role in nuclear interactions.

Light mesons and the residual nuclear force

Pions are responsible for the residual nuclear force that binds nucleons (protons and neutrons) together inside the nucleus.

This force operates over very short distances - a few femtometers - and is essentially a remnant of the strong force that binds quarks within nucleons.

For example, two protons - which would normally repel each other due to electrostatic forces - remain bound in the nucleus thanks to the constant exchange of pions.

Multiple interactions: strong, weak, and electromagnetic

Because they are made of quarks, mesons are subject to all three fundamental interactions affecting massive particles:

- Strong force: Their primary interaction. Mesons are held together by the strong force via gluons and participate in collisions and transformations inside nuclei as well as in high-energy experiments.

- Weak force: Mesons decay through the weak interaction. For example, in $\pi^+ \to \mu^+ + \nu_\mu$, a pion decays into a muon and a neutrino.

- Electromagnetic interaction: Mesons with a net electric charge (e.g., $\pi^+$, $K^-$) interact with electromagnetic fields, for instance by curving in a magnetic field or emitting radiation when accelerated.

Mesons occupy a distinctive place in the structure of matter, serving as a bridge between nucleons and quarks.

They are not stable building blocks of matter like protons and electrons, yet they are the simplest particles to exhibit the quantum behavior of the strong force at the quark level.

They are key to understanding nuclear stability, particle transmutation, and the interplay between matter and the fundamental forces.

Representative mesons

Below is a list of some of the most important mesons, along with a brief description of their main properties.

| Meson | Composition | Spin | Main features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pion \( \pi^+ \) | \( u\overline{d} \) | 0 | Lightest meson; involved in nuclear decays |

| Pion \( \pi^- \) | \( d\overline{u} \) | 0 | Produced in cosmic rays and high-energy collisions |

| Pion \( \pi^0 \) | \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} (u\overline{u} - d\overline{d}) \) | 0 | Neutral meson; decays rapidly into two photons |

| Kaon \( K^+ \) | \( u\overline{s} \) | 0 | Important in studies of CP symmetry violation |

| Kaon \( K^- \) | \( s\overline{u} \) | 0 | Decays via the weak interaction |

| Kaon \( K^0 \) | \( d\overline{s} \) | 0 | Forms oscillating \( K^0 \) / \( \overline{K}^0 \) systems |

| J/psi | \( c\overline{c} \) | 1 | Discovered in 1974; unusually long-lived for a meson |

| D meson | \( c\overline{d} \) or \( c\overline{u} \) | 0 | Contains a charm quark; used in weak interaction studies |

| B meson | \( b\overline{u} \), \( b\overline{d} \), etc. | 0 or 1 | Crucial for testing violations of fundamental symmetries |

History

In early atomic models, it was unclear what kept the nucleus from flying apart. Protons, all carrying a positive charge, should have strongly repelled each other due to electrostatic forces.

To explain nuclear stability, physicists hypothesized the existence of a much stronger force - powerful enough to overcome electrical repulsion.

This became known as the strong force.

Why don’t we notice it?

Despite its immense strength, the strong force acts only over an extremely short range, comparable to the size of an atomic nucleus.

That’s why we never experience it directly in daily life: almost all the forces we encounter - from chemical reactions to mechanical motion - are electromagnetic in nature, with gravity being the only common exception.

Yukawa’s theory (1934)

In 1934, Japanese physicist Hideki Yukawa proposed a model in which the strong force between nucleons was carried by a particle - much like the photon carries the electromagnetic force.

To account for the force’s short range, Yukawa reasoned that this particle must have mass, roughly 300 times that of the electron - about one-sixth the mass of the proton.

The birth of the meson

Because its predicted mass lay between that of the electron and the proton, the particle was named a meson - from the Greek for “intermediate.”

At the time, electrons were already classified as leptons (“light”), while protons and neutrons were known as baryons (“heavy”).

Cosmic rays and the discovery of the muon

In 1937, two research teams - one led by Anderson and Neddermeyer, the other by Street and Stevenson - detected intermediate-mass particles in cosmic rays. At first, these seemed to match Yukawa’s predicted meson.

For a time, many believed the missing particle had been found.

However, the measured mass was slightly off, its lifetime did not match expectations, and it interacted only weakly with nuclei - making it unlikely to be the strong force carrier.

In 1947, Cecil Powell’s team in Bristol, building on theoretical work by Marshak, discovered that the “mystery particle” was in fact two distinct species:

- The pion (π): Yukawa’s predicted particle, which interacts strongly with nucleons

- The muon (μ): lighter, non-participatory in the strong force, behaving instead like a heavy electron

Pions are produced in the upper atmosphere but decay rapidly.

One of their decay products, the muon, has a much longer lifetime and can reach sea level - making it the most frequently detected cosmic-ray particle in laboratories.

Although initially classified as a meson because of its mass, the muon does not participate in strong interactions.

Today, it is classified as a lepton, not a meson.

And the story of the strong force continued to unfold from there…