Residual Strong Force

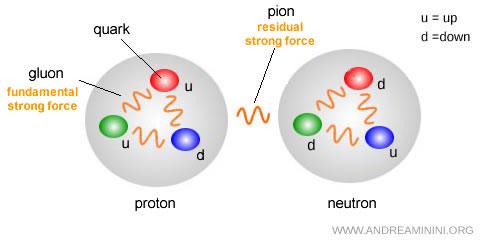

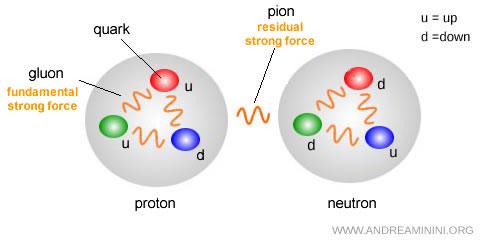

The residual strong force is a short-range attractive interaction that binds protons and neutrons within the atomic nucleus. It arises from the exchange of virtual pions between nucleons.

The strong interaction manifests in two distinct forms:

- Fundamental strong force

This acts between quarks and gluons inside nucleons (protons and neutrons). Mediated by gluons, it’s responsible for quark confinement and operates at subnuclear scales, with a range smaller than a femtometer (≲ 1 fm). - Residual strong force

This acts between nucleons within atomic nuclei. Mediated by virtual pions (mesons), it provides the cohesive force that holds the nucleus together. It operates over nuclear distances, roughly 1 - 2 femtometers. It explains how nuclei remain bound despite the electrostatic repulsion between positively charged protons.Why is it called “residual”? The term “residual” refers to the leftover influence of the fundamental strong interaction between quarks. Quarks are confined within nucleons by the fundamental strong force, but the associated field doesn't vanish entirely beyond the nucleon’s boundary. This leftover field gives rise to a secondary force between nucleons - what we call the residual strong force.

In essence, the residual force is a secondary effect of the underlying strong interaction, much like Van der Waals forces emerge as residual electromagnetic interactions between neutral molecules.

How the Residual Strong Force Operates

The atomic nucleus contains multiple protons, all carrying positive charge. Electromagnetic repulsion should push them apart - yet they remain bound.

The force that holds them together is intensely attractive but extremely short-ranged. This is the residual strong force.

It’s vastly stronger than the electromagnetic force and is responsible for binding protons and neutrons together within the nucleus.

However, its effect is limited to very short distances - on the order of ~1 - 2 femtometers.

Mechanism: Yukawa’s Model

In 1935, Hideki Yukawa proposed that nucleons attract one another via the exchange of virtual particles known as mesons, primarily identified today as pions (\$\pi^+, \pi^-, \pi^0\$).

This ongoing exchange of virtual pions acts as a kind of “quantum glue” that holds nucleons together.

Note. Pions involved in this interaction are virtual - they exist only fleetingly, in accordance with Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. Imagine two players (nucleons) continuously tossing a ball (the pion) back and forth. Even though they never touch, the repeated exchange generates a binding force between them.

Three main types of nucleon-nucleon interactions exist:

- proton - neutron (p - n)

- proton - proton (p - p)

- neutron - neutron (n - n)

The nature of the pion exchange - charged or neutral - depends on the specific pair of interacting nucleons.

The p - n Component of the Residual Force

The residual strong force between a proton and a neutron is primarily mediated by charged pions (\$\pi^+\$, \$\pi^-\$), although neutral pions (\$\pi^0\$) also contribute.

Several exchange processes can occur in the proton - neutron interaction:

- A proton emits a charged pion \$\pi^+\$ and temporarily becomes a neutron: $$ p \rightarrow n + \pi^+ $$ The \$\pi^+\$ is then absorbed by a nearby neutron, which converts into a proton: $$ n + \pi^+ \rightarrow p $$

- A neutron emits a negative pion \$\pi^-\$ and briefly becomes a proton: $$ n \rightarrow p + \pi^- $$ The \$\pi^-\$ is absorbed by a proton, which turns into a neutron: $$ p + \pi^- \rightarrow n $$

- A neutron emits a neutral pion \$\pi^0\$ but remains a neutron: $$ n \rightarrow n + \pi^0 $$ The pion is absorbed by a nearby proton, which also remains a proton: $$ p + \pi^0 \rightarrow p $$

- A proton emits a neutral pion \$\pi^0\$ and stays a proton: $$ p \rightarrow p + \pi^0 $$ The pion is then absorbed by a neutron, which likewise remains unchanged: $$ n + \pi^0 \rightarrow n $$

This continuous exchange of virtual charged pions (\$\pi^+\$, \$\pi^-\$) between protons and neutrons generates a short-range attractive force - the residual strong force - that binds them together within the nucleus.

Neutral pion exchange (\$\pi^0\$) is less potent but still contributes meaningfully to nuclear stability.

The p - p and n - n Components of the Residual Force

The residual interaction between identical nucleons (proton - proton or neutron - neutron) is predominantly mediated by neutral pions (\$\pi^0\$).

- Proton - proton interaction (p - p)

A proton emits a neutral pion and remains unchanged: $$ p \rightarrow p + \pi^0 $$ The pion is absorbed by a neighboring proton, which also remains a proton: $$ p + \pi^0 \rightarrow p $$ This exchange results in a short-range attractive force - the p - p component of the residual strong interaction. - Neutron - neutron interaction (n - n)

A neutron emits a neutral pion and stays a neutron: $$ n \rightarrow n + \pi^0 $$ The pion is absorbed by another neutron, which likewise remains unchanged: $$ n + \pi^0 \rightarrow n $$ This virtual exchange forms the n - n component of the residual strong force.

While neutral pion exchange doesn’t alter nucleon identity, it still produces a residual attraction - generally weaker than the p - n interaction involving charged pions.

This contribution is especially important in stabilizing nuclei with a high neutron-to-proton ratio.

Note. Neutral pion exchange (\$\pi^0\$) can occur between any pair - p - p, n - n, or p - n - without changing the identity of the nucleons involved.

A Practical Example

Deuterium is the nucleus of heavy hydrogen, composed of a single proton and a single neutron bound together.

The residual strong force that holds them together arises from the virtual exchange of charged pions:

$$ p \rightarrow n + \pi^+ \quad ; \quad n + \pi^+ \rightarrow p $$

or:

$$ n \rightarrow p + \pi^- \quad ; \quad p + \pi^- \rightarrow n $$

Each nucleon alternately emits and reabsorbs charged pions, momentarily transforming into the other type.

This pion exchange creates a short-range attractive force (≈ 1 - 2 fm), ensuring the stability of the deuterium nucleus.

Note. Deuterium is the simplest nucleus in which the effects of the residual strong force are clearly observable. Without this pion-mediated interaction, deuterium would not exist.

Yukawa’s Potential

The potential associated with the residual strong force is described by an exponential function:

$$ V(r) = -g^2 \frac{e^{-\mu r}}{r} $$

Where:

- \$g\$ is the nuclear coupling constant;

- \$\mu\$ is the pion mass (in natural units);

- \$r\$ is the distance between nucleons.

At short distances (\$r \ll 1/\mu\$), the potential is strongly attractive. At larger separations, the exponential term suppresses the interaction rapidly, causing the force to vanish.

As a result, this force is effective only within the typical nucleon separation of ≈ 1 - 2 femtometers, allowing it to bind nucleons within a nucleus - but not across different nuclei. This explains, in part, why molecules remain stable.

Comparison Between the Fundamental and Residual Strong Forces

The table below outlines the primary distinctions between the fundamental strong interaction and its residual form:

| Aspect | Fundamental Strong Force | Residual Strong Force |

|---|---|---|

| Mediator | Gluons (via the color charge) | Pions (mesons) |

| Acts Between | Quarks | Nucleons |

| Domain | Within protons and neutrons | Between nucleons (nuclear scale) |

| Quark Confinement | Yes | No |

| Effective Range | < 1 fm | ≈ 1 - 2 fm |

In essence, gluons mediate the strong interaction exclusively among quarks, and their influence is confined within the boundaries of a single nucleon.

Nevertheless, a residual component of the color field "spills over" beyond the confines of individual nucleons. It is this remnant interaction that gives rise to the residual strong force, which acts between protons and neutrons in the nucleus.

Just as intermolecular forces emerge from residual dipole interactions in neutral molecules, the nuclear force can be seen as the leftover effect of the fundamental color interaction operating within nucleons.

In both cases, what appears as a distinct force at larger scales is, in fact, a subtle echo of a more fundamental interaction at play beneath the surface.