String Theory

String theory is a theoretical framework in modern physics that seeks to unify all the fundamental forces of nature, including gravity and quantum interactions, within a single, self-consistent model.

This framework represents one of the most ambitious and far-reaching attempts in contemporary physics to construct a unified description of the universe.

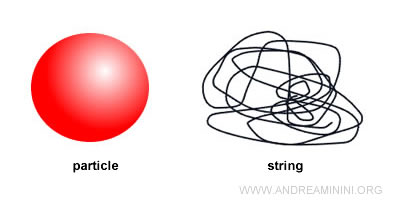

According to string theory, every force and particle in the universe is a different manifestation of a single fundamental entity: a vibrating string.

In this view, everything that exists - atoms, light, matter, space, and even time - is not made of point-like particles but of minuscule, one-dimensional strings that vibrate in various ways. From these vibrations emerge all the particles and interactions that make up the natural world.

Although still lacking experimental verification, string theory remains one of the most elegant and mathematically sophisticated attempts ever conceived to describe the ultimate fabric of reality.

The explanation

String theory stands among the most ambitious ideas in theoretical physics because it aims to reconcile the two great pillars of twentieth-century science: general relativity and quantum mechanics.

Modern physics is built upon two foundational theories, both extraordinarily precise yet fundamentally incompatible with each other.

- Einstein's general relativity describes gravity and the curvature of space-time on cosmic scales - stars, galaxies, and black holes.

- Quantum mechanics and the Standard Model describe the behavior of elementary particles in the subatomic realm (electrons, quarks, photons, and so on), as well as the three non-gravitational fundamental interactions: electromagnetic, strong nuclear, and weak nuclear forces.

Each theory works flawlessly within its respective domain, yet the two cannot be applied simultaneously.

When physicists attempt to merge them, their equations collapse into mathematical inconsistencies, and physical meaning breaks down. The universe seems to operate according to two incompatible languages.

This is the well-known conflict between general relativity and quantum mechanics - the central challenge of modern theoretical physics.

Note. This is why physicists have long pursued a theory of everything: a unified framework capable of describing both the cosmic and quantum realms within a single, consistent formulation.

String theory proposes to resolve this conflict by replacing the traditional concept of a point-like particle with that of a vibrating, one-dimensional string.

In this picture, what we call a "particle" is not a featureless point, but a tiny string capable of oscillating in multiple modes.

Each distinct vibration corresponds to a particular particle and determines its physical characteristics, such as mass and electric charge.

In essence, every vibrational pattern of a string gives rise to a different particle. One mode might correspond to an electron, another to a quark, and another still to a photon.

Note. It is as if each particle were a distinct musical note produced by the same cosmic string. A particle's properties - such as mass or charge - depend on how the string vibrates, much like a guitar string produces different notes depending on its tension and length. This is, in a poetic sense, the "music of the universe."

Mathematically, a string can be described by a function:

$$ X^{\mu}(\tau, \sigma) $$

where \( \tau \) denotes the proper time and \( \sigma \) represents the spatial coordinate along the string.

Different solutions of this function correspond to distinct vibrational modes, and therefore to different types of elementary particles.

One of the most remarkable predictions of the theory is that among the possible vibration modes there appears a massless, spin-2 particle known as the graviton.

The graviton would represent the quantum excitation of the gravitational field - the particle that mediates the force of gravity in a quantum framework.

This insight suggests that string theory could unify gravity with the other three fundamental interactions.

Note. This is a pivotal point, since gravity is the only fundamental force not encompassed by the Standard Model of particle physics. String theory naturally incorporates it through the graviton, making it one of the strongest candidates for a unified framework of all physical phenomena - the long-sought Theory of Everything.

However, there is a major implication: for the theory to be mathematically consistent, it requires more dimensions than the four we experience. Depending on the specific formulation, it may require ten or even twenty-six dimensions.

Extra dimensions

For string theory to remain consistent, space-time must possess more dimensions than those perceptible to us.

The most widely studied formulations of the theory propose:

- 26 dimensions for the bosonic string

- 10 dimensions for the superstring, which includes both bosonic and fermionic degrees of freedom

Where are these extra dimensions?

According to the theory, the additional dimensions are compactified - curled up upon themselves at incredibly small scales - so minute that they remain undetectable even with our most advanced instruments.

This can be visualized with the analogy of a garden hose: from far away, it appears as a one-dimensional line, but up close, it reveals a circular cross-section.

Similarly, the universe might contain hidden dimensions that escape observation simply because they are too small to detect directly.

The History of String Theory

In the early 1960s, physicists were exploring the strong nuclear force, attempting to describe the behavior of hadrons - composite particles built from quarks.

The theoretical frameworks available at the time struggled to account for certain striking regularities that experiments were beginning to reveal.

In 1968, a young Italian physicist named Gabriele Veneziano, working at CERN, discovered that an old mathematical function introduced by Euler, the Beta function, astonishingly reproduced the scattering amplitudes of hadronic collisions. Nobody knew why it worked, yet the formula matched the data perfectly.

$$ B(x,y)=\int_{0}^{1} t^{,x-1}(1-t)^{,y-1},dt $$

A few years later, Yoichiro Nambu, Holger Nielsen, and Leonard Susskind realized that Veneziano’s formula could be physically understood if elementary particles were not point-like, but rather one-dimensional vibrating strings.

The oscillation modes of these strings would determine observable particle properties such as mass and spin, much like the pitch of a violin string depends on the way it vibrates.

The concept was both elegant and radical, but it soon encountered serious issues. The theory predicted massless states and required extra spatial dimensions that conflicted with experimental evidence.

As a result, string theory fell out of favor for a time, while attention shifted toward gauge field theories, which became the foundation of the Standard Model and aligned more closely with experimental results.

The resurgence of the 1970s

Then, in 1974, an unexpected result reignited interest in the theory. Detailed calculations revealed that one of the string’s vibration modes corresponded exactly to a massless spin-2 particle - the graviton, the hypothetical quantum carrier of gravity.

This was a breakthrough: string theory was not just a model of the strong force, it could naturally include quantum gravity.

During the 1970s, the framework evolved into what became known as bosonic string theory, which described only bosonic degrees of freedom.

In this perspective, traditional Feynman diagrams no longer depict point-like lines meeting at vertices, but instead continuous cylindrical surfaces swept out by the motion of strings through spacetime.

Note. When two strings join or split, their corresponding cylindrical world sheets merge or branch, offering a smooth, geometric representation of quantum interaction processes.

However, this version required twenty-six spacetime dimensions and contained a tachyonic instability, suggesting an unphysical vacuum.

The next advance came with the introduction of supersymmetry, a symmetry that pairs each boson with a corresponding fermion.

This led to the formulation of superstring theory, a more consistent and stable framework that required only ten dimensions.

In the 1980s, physicists experienced what became known as the first superstring revolution.

They realized that superstring theory could, in principle, unify all fundamental interactions - including gravity - and interpret the known particles of nature as different vibrational modes of a single fundamental entity.

The theory appeared to offer a plausible candidate for a “theory of everything.”

However, the initial enthusiasm was dampened by a puzzling complication: there were not one but five mathematically consistent versions of superstring theory, each internally sound yet apparently distinct.

The five formulations of string theory

Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, string theory stood at the center of theoretical high-energy physics.

Researchers identified five self-consistent formulations of superstring theory:

- Type I

Involves both open and closed strings. Interactions among open strings generate gauge particles, while closed strings account for gravity. It is a supersymmetric theory characterized by an SO(32) gauge symmetry. - Type IIA

Consists exclusively of closed strings and exhibits non-chiral supersymmetry, meaning the two directions of string propagation are equivalent. It corresponds to ten-dimensional supergravity and is connected to eleven-dimensional M-theory through compactification. - Type IIB

Also contains only closed strings but features chiral supersymmetry, where the two propagation directions have distinct properties. It is deeply related to Type IIA via a network of dualities that exchange charges and compactified dimensions. - Heterotic SO(32)

Merges aspects of bosonic and superstring theories by combining different vibrational modes for the left- and right-moving sectors of the string. Its SO(32) gauge symmetry ensures consistency with specific formulations of ten-dimensional supergravity. - Heterotic E₈×E₈

Similar in structure to the SO(32) version but with a richer gauge group, E₈×E₈. This framework allows the construction of models compatible with the Standard Model of particle physics and with grand unified theories (GUTs).

For years, no one understood how these apparently different theories might fit together. The field entered a phase of conceptual uncertainty, even as mathematical progress continued to accelerate.

M-theory

In 1995, the physicist and mathematician Edward Witten proposed a unifying perspective, showing that the five superstring theories were not independent at all, but rather different low-energy limits of a deeper, eleven-dimensional framework known as M-theory.

In this broader context, strings are seen as one-dimensional slices of higher-dimensional objects called branes (short for “membranes”), which can extend across two, three, or more spatial dimensions.

According to this view, our entire universe could itself be a brane vibrating within a higher-dimensional “bulk.”

This insight sparked what became known as the second superstring revolution, extending the notion of strings to multidimensional objects and revealing deep dualities linking the five string theories.

Since then, string theory has matured into an extensive theoretical framework connecting quantum gravity, cosmology, and high-energy particle physics, continuing to shape the frontier of our understanding of the fundamental structure of reality.

Limits and the current status of string theory

Despite its mathematical elegance and internal coherence, string theory still lacks direct experimental evidence.

At present, it cannot be tested experimentally because the energy scales required to probe string-length phenomena far exceed those accessible to current particle accelerators, including the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN.

Consequently, string theory remains primarily a theoretical construct - an extraordinarily rich mathematical framework that has yet to be empirically verified.

Note. So far, experiments at facilities such as the LHC have found no evidence of either extra dimensions or the supersymmetric partner particles predicted by the theory. This has tempered the initial enthusiasm. By the early 2000s, many physicists had begun to regard string theory as mathematically compelling but empirically untestable.

Nonetheless, string theory has profoundly influenced modern physics. It has generated powerful mathematical tools, revealed deep connections between previously unrelated fields, and provided new perspectives on black holes, cosmology, and quantum gravity.

In short, string theory is not dead - it has evolved. While it may no longer be seen as the definitive "theory of everything," it remains one of the most fertile and intellectually stimulating areas of theoretical research.

Even if the complete theory ultimately proves incorrect, many of its insights will likely endure and contribute to the next major revolution in fundamental physics.

And so, the exploration continues.