Quark Model

The quark model describes hadrons (such as protons, neutrons, and strange particles) as composites of more elementary building blocks known as quarks.

First proposed in 1964 by Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig, it was developed to make sense of the bewildering variety of subatomic particles discovered throughout the 1950s and ’60s, and to provide a theoretical basis for the Eightfold Way - the symmetry-based classification scheme for hadrons.

The first three quarks

Initially, physicists introduced three types of quarks, referred to as flavors:

- up (u): charge $+\tfrac{2}{3}$, strangeness 0

- down (d): charge $-\tfrac{1}{3}$, strangeness 0

- strange (s): charge $-\tfrac{1}{3}$, strangeness - 1

Each quark has a corresponding antiquark with the opposite charge and strangeness.

Different combinations of quarks give rise to different particles.

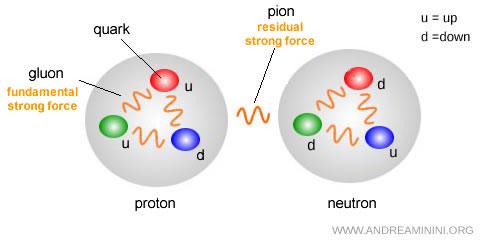

Members of the baryon family contain three quarks, while antibaryons consist of three antiquarks.

For example, the proton ($uud$) is a baryon composed of two up quarks and one down quark, while the neutron ($udd$) is made of one up quark and two down quarks. The antiproton ($\bar{u}\bar{u}\bar{d}$) is an antibaryon built from three antiquarks.

By contrast, mesons are made of a quark paired with an antiquark.

For instance, the positively charged pion $\pi^+ = u\bar{d}$ consists of an up quark and an anti-down quark.

The quark model was initially welcomed with enthusiasm, though it quickly raised some serious challenges.

Two main problems emerged during the 1960s and ’70s: one concerning quark confinement, and the other related to the Pauli exclusion principle.

The confinement problem

By the late 1960s, a major issue had become apparent: despite repeated attempts, no one had ever managed to detect a free quark. This cast doubt on the validity of the entire quark model.

To preserve the theory, physicists put forward the hypothesis of quark confinement: quarks cannot exist as free particles, but are permanently bound inside hadrons. At that stage, however, the underlying mechanism remained mysterious.

In the 1970s, deep inelastic scattering experiments showed that a proton’s electric charge is not spread evenly throughout, but concentrated in three distinct regions - an indirect confirmation of quarks.

Still, the open question was why quarks can never escape hadrons and what force is responsible for this permanent confinement.

The Pauli principle problem

Some particles appeared to violate the Pauli exclusion principle, which forbids identical fermions from occupying the same quantum state. One example is $ \Delta^{++} = uuu $, a particle seemingly made of three identical up quarks.

In 1964, Oscar Wallace Greenberg proposed a way out: quarks must carry a new property, which he called color (red, green, blue).

In other words, in addition to their flavor (up, down, strange), each quark can also be assigned a color charge.

Note. “Color” here has nothing to do with visible light. It’s a quantum charge governing the strong force. The name is purely conventional. For instance, in the hadron $ \Delta^{++} = uuu $, the three up quarks are distinguished as red, green, and blue; in this way, they are no longer identical, and the Pauli principle is upheld.

This led to a new rule: all hadrons must be color-neutral. In practice, that means quarks always combine in ways that cancel color - either three quarks of different colors, or a quark - antiquark pair with matching color and anticolor.

For a long time, this rule was thought to explain why only two- and three-quark combinations exist.

We now know that tetraquarks and pentaquarks also exist, but like ordinary hadrons, they remain overall colorless.

Today, color is recognized as a cornerstone of quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the modern theory of the strong interaction, in which gluons act as force carriers by exchanging color.

Is color just a mathematical trick? When Greenberg first introduced it, color was purely a mathematical device to preserve the Pauli principle, with no direct experimental backing. Later, however, experiments revealed that quarks behave exactly as though they interact via a threefold symmetry - precisely what color theory predicts. For that reason, color is now regarded as a fundamental property of nature, on par with electric charge or baryon number.

And the story goes on.

What ultimately rescued the quark model was the discovery of the psi meson ($ \psi $) in 1974.

This particle was electrically neutral and strikingly massive - more than three times the mass of a proton - and, to everyone’s surprise, far longer-lived than expected.

Its average lifetime was around $10^{-20}$ seconds, compared with the typical $10^{-23}$ seconds of the hadrons known at the time. Put differently, it survived roughly a thousand times longer than any comparable particle.

This unexpected stability made it clear that the $ \psi $ had to consist of a new type of quark, the charm ($ c $), bound to its antiquark:

$\psi = (c\bar{c})$

In fact, the idea of a fourth quark “flavor” had already been proposed years earlier by James Bjorken and Sheldon Glashow.

Note. Physicists had noticed an intriguing symmetry between leptons and quarks. By the early 1970s, four leptons ($e^- , \nu_e , \mu^- , \nu_{\mu} $) and three quarks ($u, d, s$) were known. This suggested there might be another quark waiting to be discovered. Bold as it seemed, the prediction turned out to be remarkably accurate.

At that stage, four leptons ($e^-, \nu_e, \mu^-, \nu_\mu$) and three quarks ($u, d, s$) were on the table, giving the picture a sense of balance.

That balance, however, didn’t last. In 1975, a new lepton was identified - the tau ($\tau^-$) - together with its corresponding neutrino ($\nu_\tau$). Suddenly the leptons numbered six, while the quarks were still only four.

This imbalance convinced many physicists that there had to be at least two more quarks yet undiscovered.

Two years later, another heavy meson - the upsilon $ \Upsilon $ - was found. It was composed of the fifth quark, soon dubbed "beauty" or "bottom", represented by the letter $ b $.

$$ \Upsilon = b\bar{b} $$

From that point on, attention turned to the hunt for the sixth quark, which was finally observed in 1995 at Fermilab. This was the "truth" or "top" quark, denoted by $ t $.

Note. Unlike the earlier ones, the top quark wasn’t discovered inside a meson but as a free $t\bar{t}$ pair produced in high-energy collisions. Its enormous mass made it decay almost instantly (for instance, $t \to W^+ b$).

With this discovery, Glashow’s symmetry was restored: six leptons ( $e^- , \nu_e , \mu^- , \nu_{\mu} , \tau^- , \nu_{\tau} $) and six quarks ($u, d, s, c, b, t $).

At the time, the fifth and sixth quarks were often called “beauty” and “truth,” but today the terms bottom and top are the standard names used in particle physics.

And the story continued from there.