Fine-structure constant

The fine-structure constant, denoted by $ \alpha $, is a pure, dimensionless quantity, $ \alpha = 1/137 $, that sets the intrinsic strength of the electromagnetic interaction between charged particles. It is defined by the relation: \[ \alpha = \frac{e^2}{4 \pi \varepsilon_0 \hbar c} \]

Where:

- \( e = 1.602176634 \cdot 10^{-19} C \) is the elementary charge

- \( \varepsilon_0 \) is the vacuum permittivity

- \( \hbar = \frac{h}{2 \pi} \) is the reduced Planck constant

- \( c \) is the speed of light in vacuum

Its numerical value is:

\[ \alpha \approx \frac{1}{137.035999177} \]

The key feature of α is that it does not depend on any system of units. It is a genuinely universal constant.

Note. Early atomic spectroscopists expected each electronic transition to produce a single, sharp spectral line. Instead, some lines appeared split into multiple, closely spaced components. This phenomenon, called fine structure, was explained in 1916 by Arnold Sommerfeld. By extending Bohr’s atomic model to include special-relativistic corrections, he showed that electron energies are slightly shifted depending on the orbital’s angular momentum and relativistic motion. To quantify these splittings, he introduced the constant $ \alpha $.

In Bohr’s original hydrogen model, $ \alpha $ is essentially the ratio between the electron’s speed in the ground-state orbit and the speed of light.

Why α matters

The fine-structure constant is central to our understanding of physical law. It helps determine why atoms exist and why matter is stable.

More precisely, α controls the electromagnetic attraction between electrons and nuclei. It sets atomic radii, the strength of chemical bonds, the structure of chemistry, and even the behavior of stars.

In quantum electrodynamics (QED), $ \alpha $ is the electromagnetic coupling constant: it quantifies the interaction strength between electrons and photons.

What if $ \alpha $ were larger?

If \( \alpha \) increased, for example to \( 1/110 \), the Coulomb attraction binding electrons to nuclei would intensify.

Electrons would be pulled into tighter orbits, shrinking atoms and significantly strengthening chemical bonds.

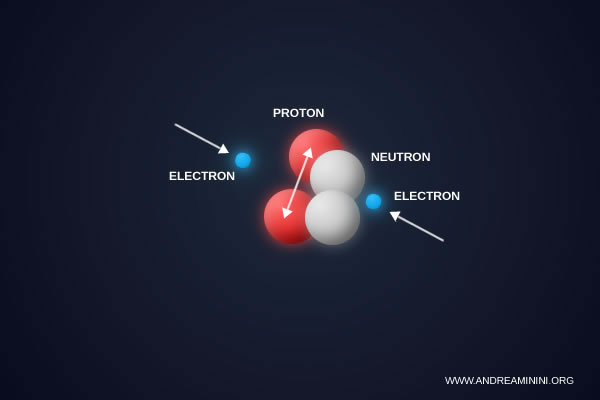

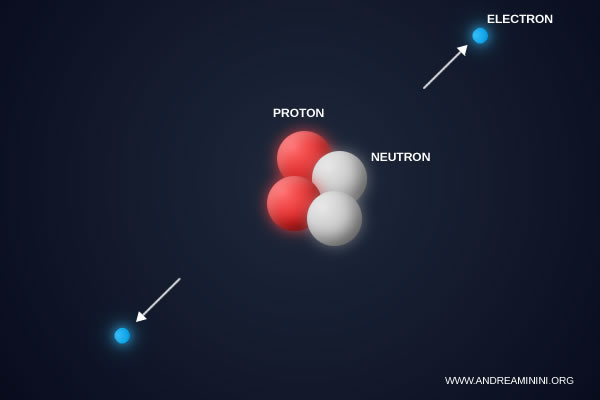

A larger \( \alpha \) would also amplify proton-proton repulsion inside nuclei. Many nuclei would become unstable because the strong nuclear force would no longer compensate for the increased electrostatic repulsion. Numerous elements would never form.

Example. Stronger, more rigid bonds would severely hinder molecular rearrangements. Chemical reactions would become rare, fundamentally disrupting the chemistry necessary for life. Biological processes rely on molecules breaking and reforming. If atomic binding were too strong, these processes would simply stop. Life’s molecular machinery would be impossible.

What if $ \alpha $ were smaller?

If \( \alpha \) decreased, for instance to \( 1/200 \), the electromagnetic pull between nuclei and electrons would weaken.

Electrons would orbit farther out, producing larger and far less stable atoms.

Under these conditions chemical bonds would be extremely fragile. Most molecules would fall apart, making organic chemistry unsustainable.

Example. Complex molecules such as DNA, proteins, and water could not exist if $ \alpha $ were too small. Stellar nucleosynthesis would also fail to produce carbon and oxygen. Key nuclear reactions, including the triple-alpha process, depend sensitively on finely tuned resonance energies. A significantly different α would shift these resonances outside the narrow range required for carbon formation.

α and the likelihood of electron photon interactions

In quantum mechanics, electrons do not interact continuously with electromagnetic radiation.

Instead, interactions occur through discrete quantum events: an electron may absorb or emit a photon, changing its energy level.

These events occur with specific probabilities, and those probabilities scale with the fine-structure constant \( \alpha \).

If \( \alpha \) were much larger, electrons would emit and absorb photons far more readily, greatly increasing electromagnetic interaction rates. If \( \alpha \) were smaller, such events would be infrequent and weak.

Note. \( \alpha \) is not itself a probability. It is the coupling constant governing the electron photon interaction. In quantum field theory the interaction amplitude is proportional to \( \sqrt{\alpha} \), while transition probabilities scale with \( \alpha \approx 1/137 \). This motivates the common, informal statement that 1/137 measures how easily an electron can exchange a photon.

In atoms, electrons occupy discrete energy levels.

To transition to a higher level, an electron must absorb a photon with the appropriate energy.

The likelihood of such an absorption is determined by \( \alpha \). A larger α increases the electron’s coupling to the electromagnetic field, making transitions more probable.

When an electron transitions downward to a lower level, it emits a photon.

That emission probability also scales with \( \alpha \).

The small value of 1/137 provides the right balance. Transitions occur often enough to produce the rich atomic spectra observed in experiments but not so often as to destabilize atoms. This delicate balance is essential for the structure and stability of matter.

Notes

Further considerations on the fine-structure constant

- The running of $ \alpha $ with energy

Despite its name, the fine-structure constant is not strictly constant. In quantum electrodynamics it “runs” with the energy scale of the interaction. At low energies, in the Thomson limit, its value is approximately $$ \alpha \approx \frac{1}{137} $$ At higher energies, vacuum polarization causes the effective electromagnetic coupling to grow, reaching values on the order of $$ \alpha \approx \frac{1}{127} $$ in high-energy collisions at modern particle accelerators. - The multiverse conjecture

Certain versions of the multiverse conjecture propose that a vast ensemble of universes exists, each with different values of fundamental constants, including α. In this framework, our universe would be one in which α assumes the specific value required to support stable matter, roughly $ \alpha \approx \frac{1}{137} $. Nonetheless, the multiverse remains a speculative, non-empirical idea and cannot be regarded as a definitive explanation for the observed value of α. - The anthropic principle

Some theorists argue that the value of $ \alpha $ may be constrained by anthropic considerations. According to this view, we measure α = 1/137 simply because only universes with similar values can host observers capable of measuring it.Note. By itself, the anthropic principle does not offer a dynamical account of why α takes its particular value. It states only that observers arise in universes compatible with their existence, which limits its explanatory force and can render it logically circular without further theoretical support.

- $ \alpha $ as a universal point of reference

Because the fine-structure constant $ \alpha = \frac{1}{137} $ is dimensionless and appears uniform throughout the observable universe, any advanced civilization studying electromagnetism would infer the same value. In that sense, α could serve as a shared scientific invariant among intelligent species, functioning as a kind of universal reference encoded directly in the laws of physics.

- Does $ \alpha $ vary across space or time?

According to cosmological models, the value of $ \alpha $ seems to have settled very early after the Big Bang. Laboratory measurements and most astrophysical observations show no compelling evidence of variation. Nevertheless, the question remains an active area of research. In 1999, one group analyzing absorption features in the spectra of distant quasars reported a slight deviation from today’s value: $$ \frac{\Delta \alpha}{\alpha} = (-5.7 \pm 1.0) \times 10^{-6} $$ If accurate, this would imply that the fine-structure constant may not be perfectly invariant across cosmic scales. Follow-up studies using different techniques and datasets, however, have not confirmed this result. At present the issue remains unresolved, with no decisive evidence either for variation or for strict immutability.

And so on.