Standard Model of Particle Physics

The Standard Model is the framework that describes all known fundamental particles and the forces acting between them - except for gravity.

According to the Standard Model, all matter is built from elementary particles grouped into three families (or generations):

- Quarks: up, down, strange, charm, bottom, and top.

- Leptons: the electron, muon, tau, and their three corresponding neutrinos.

Each particle has a corresponding antiparticle with opposite quantum numbers. This means there are also six antiquarks and six antileptons.

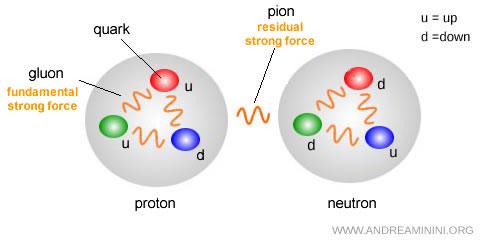

Note. Quarks also carry a “color” charge (red, green, or blue). Altogether, this gives 12 leptons (6 leptons plus 6 antileptons) and 36 quarks (12 quarks and antiquarks × 3 colors).

In addition, there are the gauge bosons - the particles that mediate the fundamental forces:

- photon (electromagnetic force)

- gluons (strong force), of which 8 have been observed

- W⁺, W⁻, and Z bosons (weak force)

The $ W^+ $, $ W^- $, and $ Z^0 $ bosons were first predicted in the 1960s by Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam, and Steven Weinberg as part of electroweak theory, which unifies electromagnetism and the weak interaction.

They were finally observed at CERN in Geneva in 1983, a breakthrough that earned Carlo Rubbia and Simon van der Meer the 1984 Nobel Prize in Physics.

In 2012, the discovery of the Higgs boson was confirmed, explaining why many fundamental particles possess mass.

Note. In total, the Standard Model includes 61 elementary particles: 48 fermions (36 quarks and 12 leptons, counting both particles and antiparticles) plus 13 force carriers (the photon, three weak bosons W⁺, W⁻, Z, eight gluons, and the Higgs boson).

When did the Standard Model take shape?

The term “Standard Model” came into common use in the 1970s, when particle physics had matured into a consistent and nearly complete theoretical framework.

During this period, thanks to the work of Murray Gell-Mann and others, the quark model was completed and quantum chromodynamics (QCD) was developed - a theory that describes the strong force through the exchange of gluons.

Step by step, experimental discoveries confirmed the model’s predictions, establishing it as the cornerstone of modern particle physics.

The Limits of the Standard Model

Today, the Standard Model is the most rigorously tested theory in all of physics.

But it is not the final word. It successfully unifies only three of the four fundamental forces of the universe:

- the electromagnetic force, carried by the photon

- the weak force, carried by the W and Z bosons

- the strong force, carried by gluons

The fourth force, gravity, is missing. A consistent quantum theory of gravity remains out of reach.

Most notably, the Standard Model is not compatible with Einstein’s general relativity, the theory that describes gravity on cosmic scales.

It also leaves major questions unanswered: it does not account for dark matter or dark energy, and it offers no explanation for why there are exactly three particle families.

This is why physicists often speak of the need for a “theory beyond the Standard Model,” which has yet to be discovered.

Note. One of the great goals of modern theoretical physics is to find a deeper framework - a Theory of Everything (ToE) - that unites the Standard Model with relativity and provides a coherent picture of the universe at every scale.

The search continues.