Fundamental Interactions

All physical phenomena - from the tiniest subatomic processes to the vast workings of the cosmos - can be traced back to four fundamental interactions (or fundamental forces):

- Electromagnetic

- Strong nuclear

- Weak nuclear

- Gravitational

In modern physics, these forces are described by quantum field theory: each force is associated with its own quantum field, and interactions occur through the exchange of force-carrying particles, known as gauge bosons.

For instance, the carrier of the electromagnetic force is the photon; the strong force is mediated by gluons (between quarks) or mesons (pions) between nucleons; the weak force by the W+, W-, and Z0 bosons. Gravity, in theory, is mediated by the graviton - an as-yet hypothetical particle that has never been detected.

It’s possible that these forces are different low-energy manifestations of a single primordial force from the early universe. However, no fully unified theory has yet been discovered, so they are still treated as distinct.

In other words, today’s framework blends Maxwell’s and Einstein’s field theories with the quantization of quantum mechanics, describing interactions as exchanges of mediating particles.

This framework - known as the Standard Model (excluding gravity) - forms the backbone of modern particle physics.

Electromagnetic Interaction

Two electrically charged bodies exert a force on each other: attractive if their charges are opposite, repulsive if they’re the same.

The Coulomb law describes this force precisely, where q represents the charges of the bodies and d their separation.

From a quantum field theory perspective, the electromagnetic field is quantized, and its quanta are photons.

In this view, the Coulomb force is not a direct action-at-a-distance, but the result of virtual photon exchange between charged particles.

Here, the photon is the force carrier of the electromagnetic interaction.

Example

Consider two electrons. Each produces an electromagnetic field and can emit a virtual photon that exists only for a fleeting instant.

When they come close enough, each absorbs a virtual photon (γ) from the other, altering its momentum.

Since both electrons carry the same negative charge, the net effect is repulsion - their paths are deflected in a way that pushes them apart.

This continuous exchange of virtual photons is the quantum underpinning of Coulomb’s law.

Note: Virtual photons cannot be directly observed and can temporarily have properties forbidden to real photons (for example, an effective nonzero mass over extremely short timescales).

This quantum picture matches Coulomb’s law at low energies but also accounts for more complex effects, such as the emission of electromagnetic radiation and high-energy scattering.

Strong Nuclear Interaction

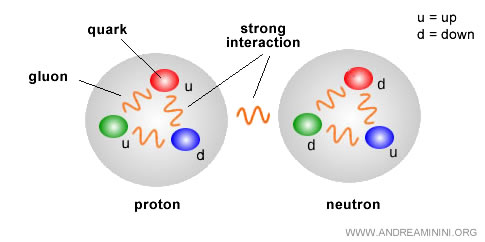

The strong force binds quarks together inside protons and neutrons, and in turn holds those nucleons together inside atomic nuclei.

It is the essential glue that keeps nuclei from flying apart.

This force is mediated by gluons (between quarks) and, at the nuclear scale, by pions as virtual mesons.

Example

Inside a proton or neutron is a dynamic “sea” of gluons and light quark - antiquark pairs constantly appearing and vanishing under the rules of quantum chromodynamics (QCD).

1] Emission

Take a proton, made of two up quarks ($u$) and one down quark ($d$).

A gluon inside the proton $(uud)$ produces a $d\bar{d}$ pair (a down quark and an anti-down quark).

The anti-down quark $\bar{d}$ pairs with one of the proton’s up quarks, forming a $\pi^+ = (u\bar{d})$ pion, which is emitted.

Inside the nucleon, the remaining up and down quarks combine with the down quark from the $d\bar{d}$ pair, creating $udd$ - a neutron.

$$ [uud]_{\text{proton}} \quad \xrightarrow{\text{gluon} \to d\bar{d}} \quad [udd]_{\text{neutron}} + [u\bar{d}]_{\pi^+} $$

The $\pi^+ = (u\bar{d})$ pion leaves as a virtual meson, existing just long enough to be absorbed by a nearby nucleon.

2] Absorption

Suppose a neutron $(udd)$ absorbs a $\pi^+ = (u\bar{d})$ pion.

The anti-down quark $\bar{d}$ annihilates with a down quark $d$ in the neutron.

The pion’s up quark then pairs with the neutron’s remaining $ud$ quarks, converting it into a proton $(uud)$.

$$ n(udd)_{\text{neutron}} + \pi^+(u\bar{d}) \quad \longrightarrow \quad p(uud)_{\text{proton}} $$

This constant exchange of virtual pions between nucleons produces the residual strong force that holds nuclei together.

Weak Interaction

The weak interaction acts on both leptons (such as electrons and neutrinos) and quarks. It’s the only fundamental force capable of changing a quark’s flavor.

It drives processes such as beta decay, enabling unstable atoms to convert a neutron into a proton or vice versa.

The force carriers for the weak interaction are the $W^+$, $W^-$, and $Z^0$ bosons.

Example (β⁻ decay)

In β⁻ decay, a neutron turns into a proton when one of its down quarks changes into an up quark, emitting a $W^-$ boson.

Initially, the neutron inside the nucleus consists of one up quark ($u$) and two down quarks ($d$):

$$ n = (u,d,d) $$

One down quark undergoes a flavor change via the weak force:

$$ d \;\longrightarrow\; u + W^- $$

The $W^-$ boson, being massive and unstable, exists only briefly before decaying into an electron $e^-$ (the observed beta particle) and an electron antineutrino $\bar{\nu}_e$:

$$ W^- \;\longrightarrow\; e^- + \bar{\nu}_e $$

The new quark arrangement $(u\,u\,d)$ corresponds to a proton.

Thus, the complete β⁻ decay reaction is:

$$ n \;\longrightarrow\; p + e^- + \bar{\nu}_e $$

The energy for this transformation comes from the neutron - proton mass difference. Part of the neutron’s mass becomes kinetic energy and the rest mass of the emitted particles.

Note: The weak force is the only interaction that can change quark type (from down to up or vice versa). It operates in unstable nuclei (to reach a more stable configuration) and in free neutrons, which decay into protons after about 14 minutes. In stable nuclei, neutrons do not decay because the transformation would require more energy than is available within the nucleus.

Gravitational Interaction

Any two masses attract each other with a force proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of their separation.

Newton’s law describes this universal pull, which operates from the scale of atoms to entire galaxies.

In theory, gravity’s force carrier is the graviton.

Note: The graviton has not been observed experimentally; it remains a theoretical construct.

The Birth of the Force Carrier Concept

In classical physics, back in Newton’s era, forces were imagined as instantaneous “actions at a distance”: two bodies could attract or repel each other without anything physically connecting them.

In the 19th century, James Clerk Maxwell transformed that view. He showed that forces act through fields permeating space, which transmit changes at a finite speed. If an electric charge changes, the effect doesn’t happen everywhere at once - it travels outward as a wave in the field.

Then came Einstein’s revolution: special relativity established that the speed of light is the ultimate speed limit - nothing, not even the influence of gravity or electromagnetism, can propagate faster.

This meant that a field doesn’t respond instantaneously but carries changes with a built-in delay.

In the 1920s and ’30s, quantum field theory took this picture a step further. Fields were no longer continuous “backgrounds” but quantized - made up of discrete packets called “quanta.”

The smallest possible ripples in a field correspond to force-carrying particles (also known as gauge bosons or quantum mediators).

Each fundamental field has its own carrier particle: photons for the electromagnetic field, gluons for the strong interaction, and so on.

Example: When two electrons repel each other, they’re not simply “pushing” via a continuous field - they’re exchanging virtual photons. These aren’t ordinary photons like those in visible light: they can’t be directly detected, and they’re not bound by the same energy - momentum rules as real particles. They exist for only a fleeting instant - just long enough to do their job - before disappearing. This process is often illustrated with a Feynman diagram.

From this quantum perspective, a force is no longer an invisible push or a smooth, continuous field - it’s the exchange of particles.

This is the essence of the force carrier idea: there are no instantaneous interactions. Forces propagate at a finite speed through fields, and in the quantum view, those fields are built from particles.

By trading these particles back and forth, matter interacts - producing what we perceive as force.

How Force Carriers Operate

The process typically follows four stages:

- Emission: a “source” particle emits a (virtual) force carrier.

- Propagation: the carrier moves through space-time for an extremely short duration.

- Absorption: a “target” particle absorbs the carrier, altering its momentum and energy.

- Effect: the change in the target manifests as attraction, repulsion, or transformation - depending on the particles’ properties. The nature of the interaction (whether it pulls, pushes, or transforms) depends on charges, quantum numbers, and symmetries - not on the carrier itself.

For example: In gravity, the interaction is always attractive (e.g., an apple falling toward Earth). In electromagnetism, opposite charges attract while like charges repel (e.g., two magnets with the same pole facing). In the strong nuclear force, the interaction is attractive at typical nuclear distances - holding quarks together - but turns repulsive at extremely short range to prevent them from overlapping. The weak nuclear force is different: it’s not about attraction or repulsion but about transformation, changing one particle type into another (e.g., beta decay turning a neutron into a proton).

A common analogy likens this to two ice skaters throwing snowballs at each other: each throw makes them recoil and drift farther apart.

However, the analogy is limited - force carriers can just as easily produce attraction or transform particles entirely, depending on the interaction.

Summary

The table below outlines the main properties of the four fundamental forces:

| Force | Force Carrier | Range | Relative Strength* | Primary Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gravitational | Graviton (hypothetical) | Infinite | ~ 10-38 | Attraction between masses; governs planetary motion and cosmic structure |

| Electromagnetic | Photon (γ) | Infinite | ~ 10-2 | Attraction/repulsion between charges; electric, magnetic, and light phenomena |

| Strong Nuclear | Gluons (g) between quarks; mesons between nucleons | ~ 10-15 m | 1 (strongest) | Binds quarks into nucleons; holds protons and neutrons in the nucleus |

| Weak Nuclear | W+, W-, Z0 bosons | ~ 10-18 m | ~ 10-5-10-13 | Radioactive beta decay; drives nuclear fusion in stars |

*Relative to the strength of the strong nuclear force.

And that’s the foundation on which our current understanding of forces is built.