Coupling Constant

In theoretical physics, the coupling constant quantifies the strength of an interaction between particles.

It is the parameter that determines how strongly two particles interact through a given fundamental force.

Put simply, the larger the coupling constant, the stronger the interaction.

- A small constant corresponds to a weak interaction (e.g., QED: $\alpha \approx 1/137$). This makes perturbative methods and series expansions feasible.

- A large constant signals a strong interaction (e.g., QCD at low energies: $\alpha_s \sim 1$). In such cases, perturbative approaches break down.

What is perturbation theory? Perturbation theory is a mathematical tool used to tackle otherwise intractable problems in physics. If the interaction is weak, it can be treated as a small “perturbation” of a simpler, non-interacting system. This is why perturbative methods are only valid when the coupling constant is small.

Here are some examples of coupling constants for the four fundamental forces of nature:

| Interaction | Constant | Symbol | Typical Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electromagnetic | Fine-structure constant | α | ≈ 1/137 |

| Strong (QCD) | Strong coupling | αs | Variable: ≈ 0.1 - 1 |

| Weak | GF (Fermi constant) | - | ≈ 1.166 × 10-5 GeV-2 |

| Gravitational (in natural units) | G | - | Extremely weak |

The Beta Function

In quantum field theory, coupling constants are not truly constant; they vary with the energy scale.

The coupling constant evolves with energy (and therefore with distance) according to the beta function.

For example, in QED (quantum electrodynamics), the electromagnetic coupling $ \alpha $ depends on the interaction energy $ E $:

$$ \alpha(E) \ne \alpha(0) \quad \text{(the effective charge grows with energy)} $$

This effect is known as vacuum screening. Because of quantum fluctuations, the vacuum behaves like a dielectric medium that “hides” part of the charge at low energies (i.e., at large distances).

At higher energies (or shorter distances), screening is less effective, so the effective charge increases.

Example. The quantum vacuum acts like a dielectric because virtual electron - positron pairs polarize in the presence of a charge. For instance, near a positive charge $q$, the negative components of virtual pairs are pulled in, while the positive ones are pushed out. This rearrangement of the field reduces the observable charge at long range. The net effect is that the effective charge $q_e(r)$ measured far away is smaller than the bare charge $q$.

By contrast, in QCD (quantum chromodynamics), the strong coupling $\alpha_s$ decreases as the energy or momentum transfer squared $Q^2$ increases:

$$ \alpha_s(Q^2) \downarrow \text{ as } Q^2 \uparrow \quad \text{(asymptotic freedom)} $$

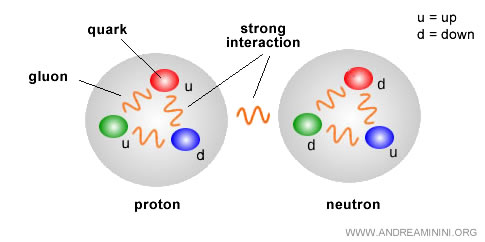

This effect, called anti-screening, arises from gluon self-interactions, since gluons themselves carry color charge (unlike photons, which are neutral).

The result is that at very short distances (high energies), the interaction between quarks weakens, and quarks behave almost like free particles inside a hadron (e.g., a proton or a neutron). This phenomenon is known as asymptotic freedom.

However, when a quark tries to escape from a hadron, the interaction with the color field grows rapidly, becoming so strong that separation is impossible. This phenomenon is known as quark confinement.

Note. This concept is central to understanding effects such as asymptotic freedom, vacuum screening, and the structure of the fundamental interactions. For instance, it explains why in high-energy colliders like the LHC, quarks appear to interact only weakly, even though at larger distance scales confinement keeps them bound inside hadrons.

Notes

A few additional remarks and side notes:

- In a gauge theory (e.g., QED or QCD), the coupling constant $g$ enters directly into the Lagrangian: $$ \mathcal{L}_{\text{int}} = g \, \bar{\psi} \gamma^\mu A_\mu \psi $$ where $g$ is the coupling constant, $A_\mu$ is the gauge field (e.g., photon, gluon), and $\psi$ is the matter field (e.g., electron, quark).

And so forth.