Discrete Symmetries in Particle Physics: C, P, and T

In particle physics, C, P, and T symmetries are discrete symmetries that describe how the fundamental laws of nature behave under specific idealized transformations.

They do not involve continuous changes, such as rotations or translations, but instead correspond to precisely defined operations that fundamentally alter the physical system under consideration.

The principal discrete symmetries studied in particle physics are:

- C symmetry (charge conjugation)

This transformation replaces each particle with its corresponding antiparticle, reversing the sign of all charges. It characterizes how physical laws behave when matter is exchanged with antimatter. - P symmetry (parity)

This corresponds to a spatial inversion of the coordinates, analogous to a mirror that exchanges left and right. It probes whether a physical process remains invariant under spatial reflection. - T symmetry (time reversal)

This consists in reversing the direction of time and examining a process as if it were played backward. It tests whether the laws of physics admit the same evolution toward the past as toward the future.

For a long time, these symmetries were assumed to be universally valid. This assumption was consistent with the prevailing view of nature as intrinsically symmetric.

However, beginning in the 1950s, a series of experiments demonstrated that some of these symmetries are violated, most notably within the weak interaction. The discovery of such violations profoundly reshaped our understanding of fundamental laws and remains a central theme of modern particle physics.

The violations of C, P, and CP reveal that nature is not perfectly symmetric, whereas the conservation of CPT stands as one of the most robust and firmly established principles of contemporary theoretical physics.

Within this framework, the study of discrete symmetries continues to play a central role, both as a conceptual foundation of the Standard Model and as a guide in the search for new theories that extend beyond it.

C Symmetry (Charge Conjugation)

C symmetry, referred to as charge conjugation, consists in replacing each particle with its corresponding antiparticle.

It is therefore a transformation that acts directly on the identity of elementary particles, reversing all additive quantum numbers associated with charges.

For example, a negatively charged particle such as an electron is transformed into a particle with identical mass and spin but opposite charge, namely a positron.

From a physical standpoint, the C transformation reverses the sign of all charges, not only the electric charge but also the charges associated with other fundamental interactions, such as weak charge and color charge.

For instance, an up quark with electric charge \( +\tfrac{2}{3} \) and a given color charge is transformed, under the action of C symmetry, into an up antiquark with electric charge \( -\tfrac{2}{3} \) and the corresponding anticolor. In the same way, a neutrino is transformed into its antineutrino, with weak quantum numbers of opposite sign.

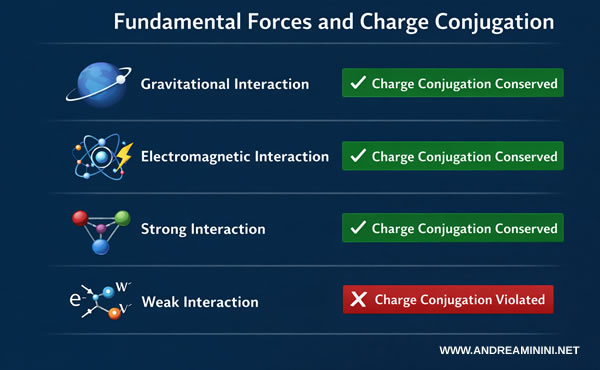

Which Fundamental Interactions Preserve C Symmetry?

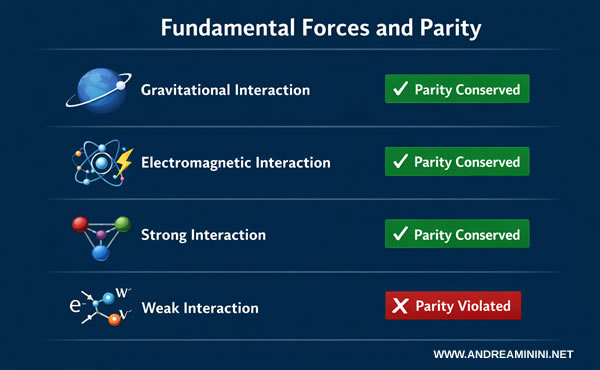

The electromagnetic, strong, and gravitational interactions preserve C symmetry.

This means that, upon replacing all particles with their corresponding antiparticles, the equations describing these interactions retain the same mathematical form.

The weak interaction, by contrast, violates C symmetry in a maximal manner.

A particularly clear conceptual example is provided by neutrinos. A left handed neutrino, after a C transformation, becomes a left handed antineutrino. In the Standard Model, however, left handed antineutrinos do not participate in weak interactions. This provides a direct demonstration that C symmetry is not conserved.

This violation also plays a crucial role in cosmology, because together with CP violation it contributes to explaining the observed excess of matter over antimatter in the universe.

P Symmetry (Parity)

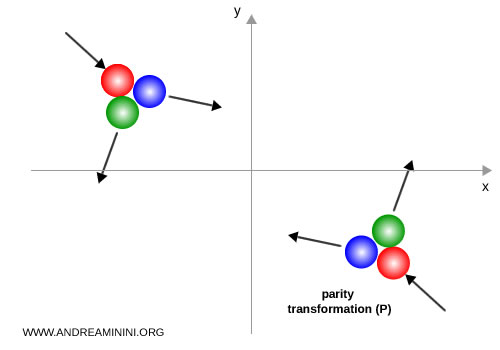

The parity transformation (P) reverses the sign of the spatial coordinates. In three dimensions, this operation is equivalent to a central inversion through the origin.

\[ (x,y,z) \rightarrow (-x,-y,-z) \]

In other words, each Cartesian axis is inverted with respect to its original orientation.

From a physical point of view, the parity transformation is equivalent to observing a phenomenon through an ideal mirror that reverses all spatial directions.

If P symmetry is conserved, the physical process and its mirror image are governed by the same laws and are physically indistinguishable.

For example, if a red billiard ball strikes two other balls, the physical process unfolds in the same way even after all spatial coordinates are inverted. In this case, the collision dynamics remain invariant under the parity transformation, because the laws of classical mechanics governing motion and collisions are symmetric under spatial inversion.

Most fundamental interactions in physics preserve parity symmetry P, in particular the strong, electromagnetic, and gravitational interactions, which remain invariant under spatial inversion.

This means that, for these interactions, physical processes occur in the same way even when left and right are exchanged.

Not all interactions share this property, however. The weak interaction violates parity symmetry P. This violation shows that nature intrinsically distinguishes between right handed and left handed configurations, introducing a fundamental asymmetry into physical laws.

In 1957, the experiment performed by Chien Shiung Wu on the beta decay of Cobalt 60 demonstrated unambiguously that the weak interaction violates parity symmetry.

The Cobalt 60 nuclei, cooled and aligned by a magnetic field, emitted electrons preferentially in one direction, opposite to the nuclear spin, thereby breaking mirror symmetry.

Since spin is a pseudovector and does not change sign under spatial inversion, after a parity operation P the electrons would be expected to be emitted in the same direction as the spin. This behavior, however, is not observed in nature. It therefore provides clear experimental evidence of parity symmetry violation.

The conclusion was striking: at a fundamental level, nature distinguishes between left and right.

The weak interaction is chiral: only left handed components of particles, and right handed components of antiparticles, participate in charged weak interactions.

Note. In quantum mechanics, states can be classified according to their behavior under parity transformation. A state is called even if its wave function remains unchanged, and odd if its wave function changes sign. This classification is particularly useful in the study of bound states and decay processes.

T Symmetry (Time Reversal)

T symmetry refers to the invariance of physical laws under the reversal of the direction of time. In simple terms, a T transformation corresponds to reversing the orientation of the time arrow.

\[ t \rightarrow -t \]

If a theory is invariant under T, then a physical process observed backward in time is governed by the same dynamical laws as the same process evolving forward in time.

An intuitive example is provided by billiard balls. A red ball simultaneously strikes two other balls, one blue and one green, which then move away in different directions. If the scene is viewed backward in time, the two balls move toward the red ball, collide with it, and cause it to recoil. From the standpoint of the laws of motion, the physical process is equally admissible in both temporal directions, and no intrinsic distinction between past and future emerges.

At the macroscopic level, this symmetry appears to be violated by the second law of thermodynamics, which introduces a preferred direction of time associated with the monotonic increase of entropy.

This apparent asymmetry is not regarded as fundamental, but rather as an emergent phenomenon arising from statistical considerations related to the collective behavior of systems with a very large number of degrees of freedom.

At the microscopic level, by contrast, most fundamental dynamical laws are invariant under time reversal.

There is, however, an important exception. Because the CPT theorem must hold exactly, the experimental observation of CP symmetry violation necessarily implies the existence of a corresponding violation of T symmetry in weak interactions. Although this violation is fundamental, it is considerably more difficult to observe directly in physical processes.

CP Symmetry

CP symmetry is defined as the combined application of charge conjugation (C) and parity (P).

Under a CP transformation, a particle is first replaced by its antiparticle through the C operation, and the spatial coordinates of the resulting state are then inverted through the parity operation P.

After the discovery of parity violation, it was initially hoped that CP symmetry might nevertheless be conserved and could represent a deeper symmetry of nature.

Indeed, when the C and P operations are applied simultaneously to the case of neutrinos, one obtains a right handed antineutrino, in agreement with what is observed in nature.

This expectation was overturned in 1964, when the study of neutral kaon decays demonstrated that CP symmetry is also violated in weak interactions.

In particular, the behavior of kaons and antikaons was found to differ slightly, despite the application of the CP transformation.

Note. This discovery had a profound impact on theoretical physics, since CP violation is one of the necessary conditions for explaining the observed asymmetry between matter and antimatter in the universe. In the absence of such a violation, matter and antimatter would have been produced in equal amounts during the early stages of cosmic evolution and would have subsequently annihilated each other.

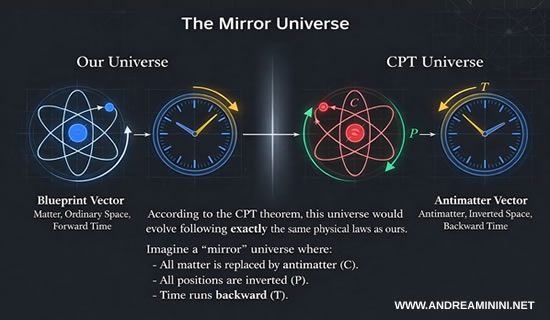

CPT Symmetry and the CPT Theorem

CPT symmetry combines all three of the discrete transformations discussed above: charge conjugation, parity, and time reversal.

The CPT theorem states that any quantum field theory that is local, Lorentz invariant, and governed by a Hermitian Hamiltonian must be invariant under the combined CPT transformation.

In other words, if Charge, Parity, and Time are simultaneously reversed, the laws of physics remain unchanged. Even if C, P, or CP are violated individually, the combined CPT transformation must be an exact symmetry.

For example, if $ \Psi $ denotes a physical state, then $ \Psi_{CPT} $ is also a physical state and obeys the same fundamental laws.

$$ \Psi \ \text{(Physical State)} \xrightarrow{C} C(\Psi) \xrightarrow{P} PC(\Psi) \xrightarrow{T} \Psi_{CPT} $$

This implies that a universe composed of antimatter, the so called mirror universe, spatially reflected and evolving backward in time, would obey exactly the same physical laws as our own universe.

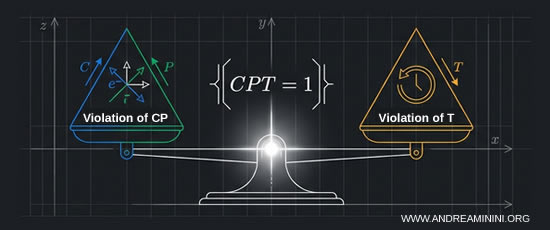

The CPT theorem also entails the existence of a violation of T symmetry.

In order to preserve CPT invariance, any violation of CP symmetry must be accompanied by a corresponding violation of T symmetry, that is, time reversal invariance.

The microscopic laws of physics are therefore not perfectly symmetric with respect to time.

Note. Since it has been experimentally established that C and P symmetries are violated, the CPT theorem implies that a violation of T symmetry must necessarily exist in order for the combined CPT transformation to remain an exact symmetry of the fundamental laws. Therefore, if CP symmetry is violated, then T symmetry must also be violated. It is important to emphasize that this form of temporal irreversibility is distinct from the thermodynamic arrow of time, which is statistical and macroscopic in origin.

To date, CPT symmetry is the only combination of these transformations that has been found to be exactly conserved in all experiments. There is currently no experimental evidence for its violation.

Any potential violation of CPT symmetry would imply a breakdown of Lorentz invariance and would require a radical revision of our fundamental physical theories.

And so on.