Higgs Boson

The Higgs boson is a fundamental particle associated with the Higgs field, an invisible and uniform quantum field that permeates all of space and endows elementary particles with mass.

The Higgs boson appears when the Higgs field becomes excited or oscillates due to an interaction involving extremely high energy.

It was discovered in 2012 at CERN in Geneva through the ATLAS and CMS experiments conducted with the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), confirming a theoretical prediction proposed in the 1960s by Peter Higgs and other theoretical physicists.

To visualize it, imagine the Higgs field as the water of an ocean and the Higgs boson as a wave that briefly rises, travels across the surface, and then dissipates.

Note. The Higgs boson does not emerge because the field contains massive particles. It is an intrinsic quantum excitation of the Higgs field itself, appearing only when the field is disturbed by an immense amount of energy, such as in the particle collisions produced by the Large Hadron Collider.

The origin of mass in elementary particles

In the Standard Model of particle physics, there are several types of fundamental particles (electrons, quarks, neutrinos, photons, and so on). Some possess mass - such as the electron and the W and Z bosons - while others, like the photon, are massless.

Where does mass come from?

In 1964, Higgs and several other theorists proposed that the universe is permeated by an invisible quantum field known as the Higgs field. This field exists everywhere, even in what we perceive as empty space.

The Higgs field is a scalar field, meaning that it is characterized by a single value at each point in space, unlike vector fields such as the electric or magnetic fields, which have both magnitude and direction.

One of its key features is that even in its lowest-energy configuration - the vacuum - it does not vanish. In physical terms, the field has a non-zero vacuum expectation value (VEV).

It is as though the entire universe were immersed in an invisible ocean of energy.

How does it give mass to particles?

As a fundamental particle moves through this omnipresent field, it interacts with it. The strength of this interaction determines the particle's inertial mass.

Particles that couple strongly to the field acquire a large mass, such as the top quark.

Particles that couple weakly to the field remain light, such as the electron.

Particles that do not couple to the field at all remain massless, like the photon.

Note. To illustrate the difference between a heavy and a light particle, imagine the Higgs field as a crowd standing along a sidewalk. A heavy particle is like a famous person who, as they walk, is immediately surrounded by fans asking for autographs - their interaction with the crowd slows their motion. A light particle, in contrast, is like an ordinary passerby who walks through the same crowd unnoticed, moving freely and unhindered.

Formally, mass arises through the Yukawa coupling between fermions and the Higgs field.

The Higgs boson itself is the quantized excitation - the quantum of vibration - of the Higgs field.

The 2012 discovery of the Higgs boson by the ATLAS and CMS collaborations at CERN provided experimental confirmation that the Higgs field truly exists.

The Higgs field does not give mass to all matter

Not all of the mass in the universe originates from the Higgs field. It accounts only for the masses of the elementary particles in the Standard Model, not for composite matter such as protons and neutrons.

The Higgs field is responsible for the rest mass of elementary particles (electrons, quarks, and the W and Z bosons).

Without the Higgs field, these particles would be massless and would all travel at the speed of light, like photons.

The Higgs field spontaneously breaks electroweak symmetry and, through its Yukawa interactions, endows each particle with a mass proportional to its coupling strength with the field.

This portion of the universe's total mass therefore arises directly from the Higgs mechanism.

However, the Higgs field does not determine the mass of composite particles.

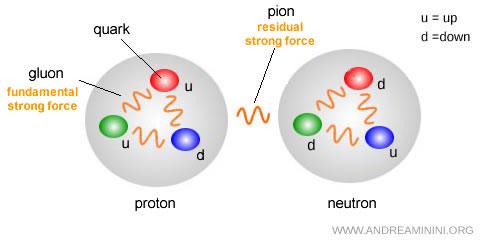

Most of the visible matter in the universe consists of protons and neutrons, which are made of quarks and gluons bound together by the strong nuclear force described by Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD).

For instance, the mass of a proton or neutron is not simply the sum of the masses of its three valence quarks. In fact, more than 98% of their mass comes from the binding energy of the gluons that confine the quarks. The combined mass of the quarks accounts for only about 1% of the proton's total mass. Where does the rest come from? It originates from the kinetic and potential energy of the quarks and gluons inside the nucleon. According to Einstein's relation $E = mc^2$, that energy manifests as mass.

The mass of ordinary matter is therefore primarily energy confined within the gluon field.

In a deeper sense, we are made more of energy bound by the strong interaction than of mass produced by the Higgs mechanism.

Consequently, most of the mass in the universe is generated by the dynamics of the strong force rather than by the Higgs field.

The Higgs field potential

At the earliest stage of the universe, the Higgs field occupied a perfectly symmetric state in which its value was zero everywhere in space. However, this configuration was unstable and inevitably transitioned to a lower-energy state.

To visualize this, imagine a small ball balanced on the top of a sombrero-shaped surface.

The height of the surface represents the potential energy of the Higgs field as a function of its value - that is, how much energy is required to maintain the field in a given configuration.

The peak of the sombrero corresponds to a local maximum, an unstable equilibrium in which the universe would be perfectly symmetric and all particles massless.

Even a tiny fluctuation is enough to break this symmetry, like a ball teetering on the top of the hat.

This process is called spontaneous symmetry breaking.

This is followed by a process known as Higgs field relaxation, in which the field naturally "rolls down" toward a region of lower potential energy.

Eventually, the Higgs field settles in a minimum-energy configuration, where it acquires a non-zero vacuum expectation value (VEV) even in empty space.

In this broken-symmetry phase, some particles (such as the W and Z bosons, quarks, and electrons) acquire mass through their interaction with the field, while others (like the photon) remain massless.

Today, the universe resides in this vacuum state of minimum potential energy, no longer "at the top" of the sombrero surface.

Even in this equilibrium, the Higgs field can still undergo small oscillations around its minimum - like a ball vibrating gently at the bottom of a valley. These quantum oscillations correspond to real, observable Higgs bosons.

In summary, the Higgs field is the "valley" in which the ball rests, while the Higgs boson is the "vibration" of that ball at the bottom of the valley.

Stable or Metastable Equilibrium?

From a theoretical physics perspective, the current minimum of the Higgs potential appears to be a local minimum, rather than the absolute global one.

This means that the universe may presently reside in a metastable state - a "false vacuum" - which could, in principle, transition at some point to a "true vacuum" characterized by a lower potential energy.

Nevertheless, according to current estimates based on measured parameters - the Higgs boson mass (≈125 GeV) and the top quark mass - the probability of such a decay occurring is extraordinarily small. If it were to happen, it would take place only on timescales vastly exceeding the current age of the universe, meaning it poses no conceivable threat within any realistic future horizon.

And so the discussion continues.