Plane Equation

The equation of a plane defines all points (x, y, z) that lie on a given plane in three-dimensional space. The general form of the plane equation is: $$ ax + by + cz + d = 0 $$ where $a$, $b$, and $c$ are the components of a vector normal to the plane, and $d$ is a constant that determines the plane’s offset from the origin.

This is one of the core equations in analytic geometry for representing surfaces in 3D space.

The plane consists of the infinite set of points that satisfy this general equation, also called the implicit form.

$$ ax + by + cz + d = 0 $$

Depending on the context, the plane can also be written in explicit form:

$$ z = mx + ny + q $$

Note: The normal vector $\vec{n} = (a, b, c)$ is perpendicular to the plane - it forms a 90° angle with every direction that lies within the plane.

A Practical Example

Consider the equation:

$$ 2x - 3y + 4z - 5 = 0 $$

Every point $(x, y, z)$ that satisfies this equation lies on the plane.

The normal vector to this plane is $\vec{n} = (2, -3, 4)$.

Any vector that lies entirely within the plane is orthogonal to this normal vector.

Plane Equation in Explicit Form

The explicit form of the plane equation is written as $$ z = m x + n y + q $$

When writing the equation of a plane in three-dimensional space, it’s commonly expressed in general form:

$a x + b y + c z + d = 0$

This form is compact, but not always the easiest to interpret.

To make the equation more readable, it helps to solve for $z$ - provided that the coefficient $c \ne 0$. In that case, we can rearrange the equation as follows:

$$ c z = -a x - b y - d $$

$$ z = - \frac{a}{c} x - \frac{b}{c} y - \frac{d}{c} $$

It’s convenient to introduce the substitutions: $m = -\frac{a}{c}$, $n = -\frac{b}{c}$, $q = -\frac{d}{c}$

so the equation becomes:

$$ z = m x + n y + q $$

This is known as the explicit form of the plane equation.

When is the explicit form applicable? You can rewrite a plane equation in explicit form only if the plane is not parallel to the $z$-axis. If $c = 0$, the equation reduces to: $$ a x + b y + d = 0 $$ In this case, the variable $z$ does not appear - meaning the plane is parallel to the $z$-axis - so it cannot be written as $z = \dots$.

Example

Consider the plane given by the equation:

$$ 2x - 3y + 4z + 5 = 0 $$

Since $c = 4 \ne 0$, we can express this in explicit form:

$$ z = -\frac{2}{4}x + \frac{3}{4}y - \frac{5}{4} $$

$$ z = -0.5x + 0.75y - 1.25 $$

This form makes it easy to see how $z$ varies with $x$ and $y$, and also simplifies graphing the plane.

Example 2

Now take the equation:

$x + 2y + 5 = 0$

Here, $c = 0$, so $z$ does not appear in the equation. The plane is parallel to the $z$-axis, and the explicit form does not apply.

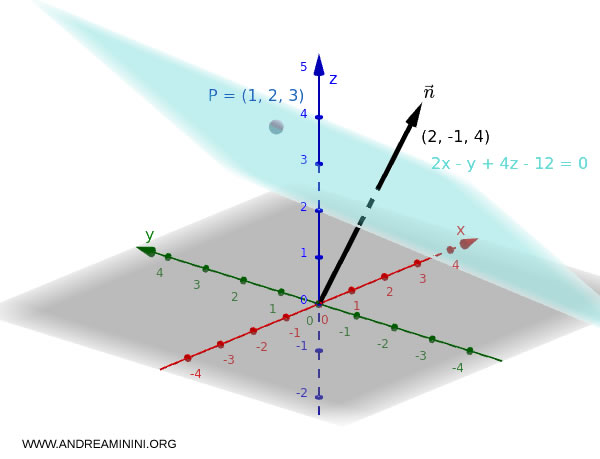

Plane Through a Given Point

If a point $P_0(x_0, y_0, z_0)$ and a normal vector $\vec{n} = (a, b, c)$ are known, the equation of the plane passing through the point is given by: $$ a(x - x_0) + b(y - y_0) + c(z - z_0) = 0 $$

Example

Let $P = (1, 2, 3)$ and $\vec{n} = (2, -1, 4)$.

The equation of the plane passing through $P$ becomes:

$$ 2(x - 1) - 1(y - 2) + 4(z - 3) = 0 $$

Expanding and simplifying:

$$ 2x - 2 - y + 2 + 4z - 12 = 0 $$

$$ 2x - y + 4z - 12 = 0 $$

This is the equation of the plane through $P = (1, 2, 3)$, perpendicular to $\vec{n} = (2, -1, 4)$.

Distance from a Point to a Plane

Given a plane $ax + by + cz + d = 0$ and a point $P(x_1, y_1, z_1)$ in space, the shortest distance from the point to the plane is calculated using the formula: $$ \text{Distance} = \frac{|a x_1 + b y_1 + c z_1 + d|}{\sqrt{a^2 + b^2 + c^2}} $$

Example

Find the distance from $P = (1, 1, 1)$ to the plane $x + y + z - 3 = 0$:

$$ \text{Distance} = \frac{|1 + 1 + 1 - 3|}{\sqrt{1^2 + 1^2 + 1^2}} = \frac{0}{\sqrt{3}} = 0 $$

Since the distance is zero, the point lies on the plane.

Special Planes in Space

Certain planes in Cartesian space are considered special because their equations involve only some of the variables, or because certain coefficients are missing.

Coordinate Planes

When the equation of a plane involves just a single variable, the plane is parallel to one of the coordinate planes.

The three primary coordinate planes are:

- The Oyz plane, defined when $ x = 0 $

- The Oxz plane, defined when $ y = 0 $

- The Oxy plane, defined when $ z = 0 $

These are called "coordinate planes" because they coincide with the planes formed by any two of the three Cartesian axes.

Planes Parallel to Coordinate Planes

When the equation takes the form $ x = k $, $ y = k $, or $ z = k $, the resulting plane is parallel to one of the coordinate planes.

- If $ x = k $, the plane is parallel to the Oyz plane

- If $ y = k $, the plane is parallel to the Oxz plane

- If $ z = k $, the plane is parallel to the Oxy plane

Here, $ k $ is any non-zero real constant $ (k \ne 0) $.

These planes have the same orientation as the coordinate planes, but they are shifted (translated) along the corresponding axis.

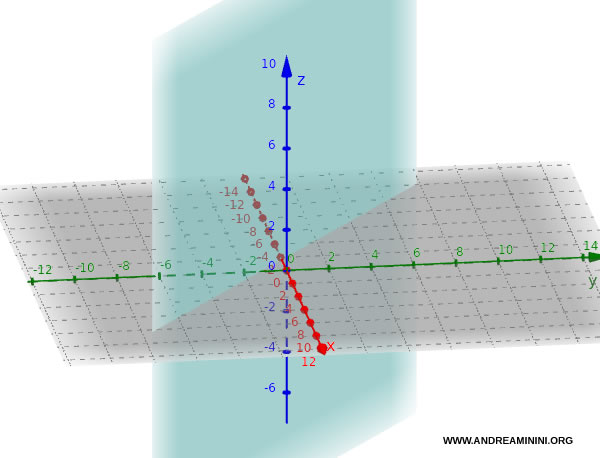

Planes with a Zero Coefficient

When one of the coefficients in the plane’s equation is zero, the plane is parallel to the corresponding axis and perpendicular to the plane defined by the other two axes.

Consider the general form of a plane equation:

$$ ax + by + cz + d = 0 $$

More specifically:

- If $ c = 0 $, the equation reduces to $ ax + by + d = 0 $. The plane is parallel to the z-axis and perpendicular to the Oxy plane.

For example, the plane $ 3x + 4y + 0 \cdot z + 5 = 0 $, or simply $ 3x + 4y + 5 = 0 $, is parallel to the z-axis and perpendicular to the Oxy plane.

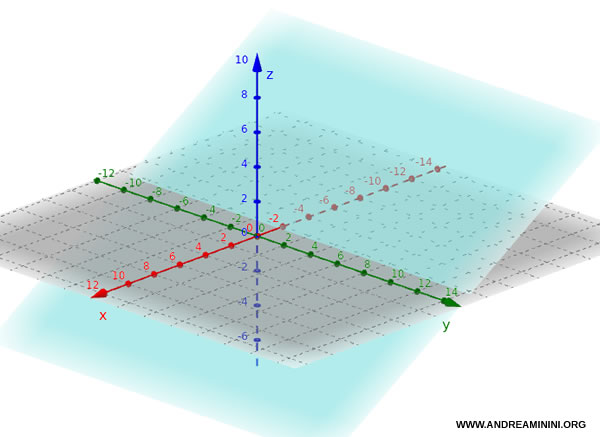

- If $ b = 0 $, the equation reduces to $ ax + cz + d = 0 $. The plane is parallel to the y-axis and perpendicular to the Oxz plane.

For example, the plane $ 3x + 0 \cdot y + 5z + 5 = 0 $, or simply $ 3x + 5z + 5 = 0 $, is parallel to the y-axis and perpendicular to the Oxz plane.

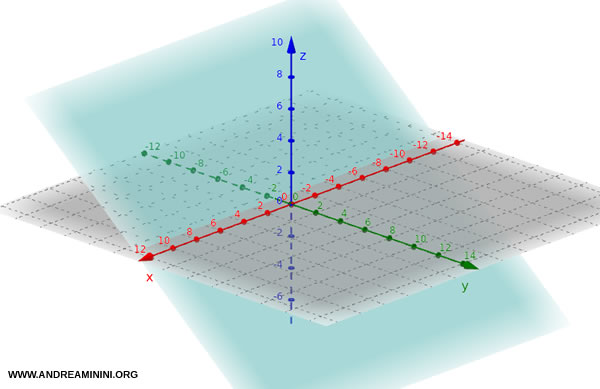

- If $ a = 0 $, the equation reduces to $ by + cz + d = 0 $. The plane is parallel to the x-axis and perpendicular to the Oyz plane.

For example, the plane $ 0 \cdot x + 4y + 5z + 5 = 0 $, or simply $ 4y + 5z + 5 = 0 $, is parallel to the x-axis and perpendicular to the Oyz plane.

Parametric Equations of a Plane

A plane can also be described parametrically using two linearly independent vectors within the plane and a reference point: $$ \vec{r}(s,t) = P_0 + s \cdot \vec{v_1} + t \cdot \vec{v_2} $$ Here, $s, t \in \mathbb{R}$ are parameters, $P_0 = (x_0, y_0, z_0)$ is the point, and $\vec{v_1}$ and $\vec{v_2}$ are direction vectors lying in the plane.

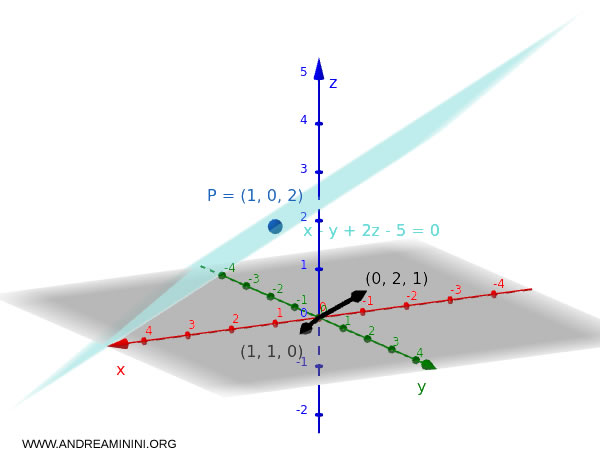

Example

Let $P_0 = (1, 0, 2)$, $\vec{v_1} = (1, 1, 0)$, and $\vec{v_2} = (0, 2, 1)$.

The parametric equation of the plane is:

$$ \vec{r}(s,t) = (1,0,2) + s(1,1,0) + t(0,2,1) $$

Expanding into Cartesian form:

$$ \begin{cases} x = 1 + s \\ y = s + 2t \\ z = 2 + t \end{cases} $$

This system describes the same plane, with $s$ and $t$ as free parameters.

To express the plane in Cartesian (implicit) form, we eliminate the parameters.

From the first equation: $s = x - 1$

$$ \begin{cases} s = x - 1 \\ y = s + 2t \\ z = 2 + t \end{cases} $$

From the third: $t = z - 2$

$$ \begin{cases} s = x - 1 \\ y = s + 2t \\ t = z - 2 \end{cases} $$

Substitute into the second equation:

$$ y = (x - 1) + 2(z - 2) = x + 2z - 5 $$

So, the explicit equation is:

$$ y = x + 2z - 5 $$

Rewriting in general (implicit) form:

$$ x - y + 2z - 5 = 0 $$

Verification: Check whether $P_0 = (1, 0, 2)$ lies on the plane. Plug the coordinates into the equation $x - y + 2z - 5 = 0$: $$ 1 - 0 + 2 \cdot 2 - 5 = 1 + 4 - 5 = 0 $$ Since the equation is satisfied, the point lies on the plane.

Proof

To derive the general form of the plane equation, let’s consider a plane $ \alpha $ that does not pass through the origin $ O(0, 0, 0) $ of the Cartesian coordinate system.

We draw a vector perpendicular to the plane $ \alpha $, intersecting it at the point $ A = (a, b, c) $.

This means that the segment $ OA $ is perpendicular to the plane $ \alpha $.

Now, select any point $ P = (x, y, z) $ lying on the plane, distinct from $ A = (a, b, c) $.

Since $ OA $ is perpendicular to the plane and $ P $ lies on the plane, the vector $ \vec{AP} $ must be perpendicular to $ \vec{OA} $.

We then connect $ O $ to $ P $, forming the segment $ OP $.

As a result, triangle $ \triangle OAP $ is a right triangle by construction.

According to the Pythagorean Theorem, the following relation holds:

$$ OP^2 = OA^2 + AP^2 $$

We now apply the distance formula in three-dimensional space:

$$ \text{Distance}^2 = (x_2 - x_1)^2 + (y_2 - y_1)^2 + (z_2 - z_1)^2 $$

The squared distance between the origin $ O(0, 0, 0) $ and the point $ A(a, b, c) $ is:

$$ OA^2 = a^2 + b^2 + c^2 $$

The squared distance from the origin to the point $ P(x, y, z) $ is:

$$ OP^2 = x^2 + y^2 + z^2 $$

The squared distance between $ A(a, b, c) $ and $ P(x, y, z) $ is:

$$ AP^2 = (x - a)^2 + (y - b)^2 + (z - c)^2 $$

Substituting into the Pythagorean identity:

$$ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = a^2 + b^2 + c^2 + (x - a)^2 + (y - b)^2 + (z - c)^2 $$

Now expand the squared differences:

$$ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = a^2 + b^2 + c^2 + x^2 - 2ax + a^2 + y^2 - 2by + b^2 + z^2 - 2cz + c^2 $$

Rearrange and simplify the expression:

$$ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 - a^2 - b^2 - c^2 - x^2 + 2ax - a^2 - y^2 + 2by - b^2 - z^2 + 2cz - c^2 = 0 $$

Combining like terms:

$$ -2a^2 - 2b^2 - 2c^2 + 2ax + 2by + 2cz = 0 $$

Divide both sides of the equation by 2:

$$ -a^2 - b^2 - c^2 + ax + by + cz = 0 $$

Which we can rewrite as:

$$ ax + by + cz - (a^2 + b^2 + c^2) = 0 $$

Letting $ d = - (a^2 + b^2 + c^2) $, we obtain the general equation of the plane:

$$ ax + by + cz + d = 0 $$

And so forth.