Equations of Surfaces in Space

In analytic geometry, a surface is defined as the set of all points whose Cartesian coordinates $x, y, z$ satisfy an equation of the form: $$ F(x, y, z) = 0 $$ This equation precisely determines which points lie on the surface.

The equation $F(x, y, z) = 0$ allows us to test whether a specific point lies on the surface: simply substitute the values of $x, y, z$ and check whether the equality holds. It also reveals the geometric shape of the surface.

Depending on the type of surface, the equation can range from very simple to highly complex.

Thanks to the equation $F(x, y, z) = 0$, we can classify surfaces into different categories, such as planes, quadrics, and others.

Algebraic Surfaces

If the function $F(x, y, z)$ is a polynomial, the surface is known as an algebraic surface.

We say it’s of degree n (or order $n$) if the polynomial has degree $n$.

First-degree surfaces are planes, described by linear equations:

$$ ax + by + cz + d = 0 $$

where $a, b, c, d$ are constants.

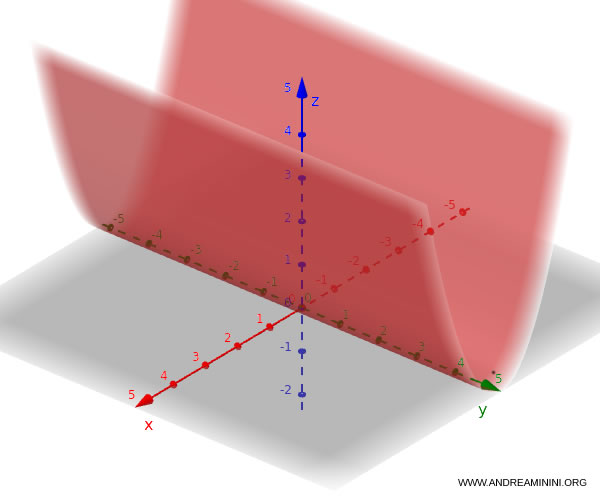

For example, this equation defines a plane: $$ 2x - 3y + z + 5 = 0 $$ This is how the plane appears in three-dimensional space.

To check if a point lies on the plane, substitute its coordinates into the equation and see if it holds true. For instance, does the point $(1, -1, 0)$ lie on the plane? Let’s test it: $$2 \cdot 1 - 3 \cdot (-1) + 0 + 5 = 2 + 3 + 5 = 10 \neq 0$$ Since the equation is not satisfied, the point does not lie on the plane.

Second-degree surfaces are called quadrics, described by quadratic equations.

Quadratic Surfaces

Quadrics are surfaces defined by a second-degree polynomial equation of the general form:

$$ ax^2 + by^2 + cz^2 + dxy + exz + fyz + gx + hy + iz + l = 0 $$

Depending on the values of the coefficients, this equation can describe a wide range of surfaces, including:

- ellipsoids

- hyperboloids

- paraboloids

- cones

- cylinders

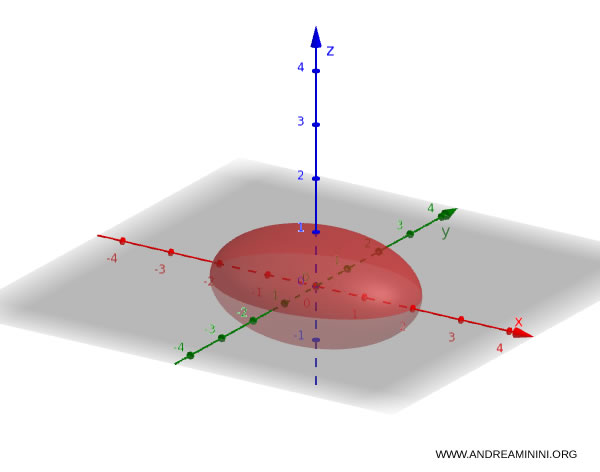

Ellipsoid

An ellipsoid is a surface that generalizes a sphere, formed by stretching or compressing the radii along the three coordinate axes. Its standard equation is:

$$ \frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} + \frac{z^2}{c^2} = 1 $$

If $a = b = c$, the surface is a sphere.

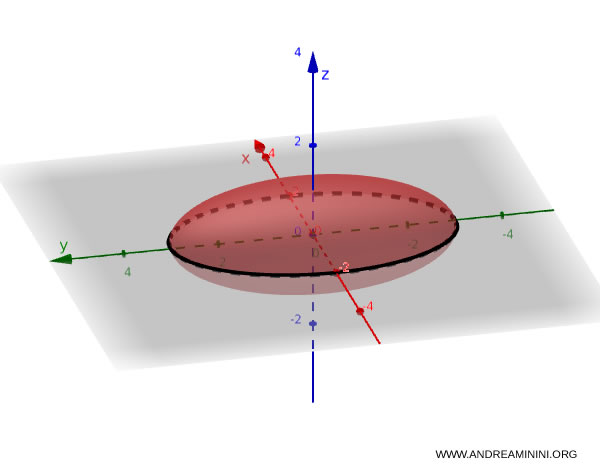

For instance, consider the equation:

$$ \frac{x^2}{9} + \frac{y^2}{4} + \frac{z^2}{1} = 1 $$

This describes an ellipsoid with semi-axes $a = 3$, $b = 2$, and $c = 1$.

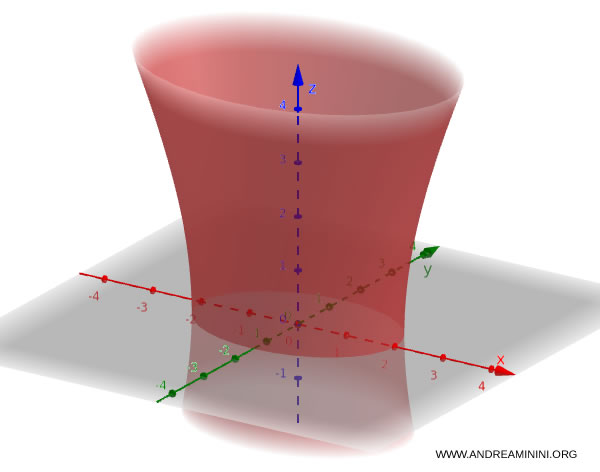

Hyperboloid

A hyperboloid is a quadric surface that can either have one continuous sheet or consist of two separate sheets.

The equation of a one-sheet hyperboloid is:

$$ \frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} - \frac{z^2}{c^2} = 1 $$

The equation of a two-sheet hyperboloid is:

$$ - \frac{x^2}{a^2} - \frac{y^2}{b^2} + \frac{z^2}{c^2} = 1 $$

Here’s a practical example of a one-sheet hyperboloid: $$ \frac{x^2}{4} + \frac{y^2}{9} - \frac{z^2}{16} = 1 $$ This surface features a narrow “waist” at the center, expanding outward both above and below.

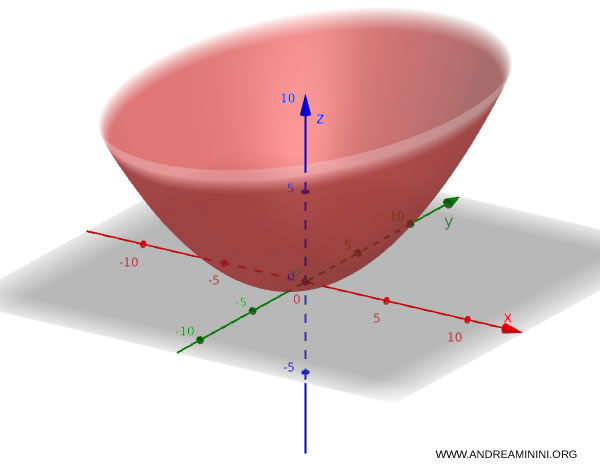

Paraboloid

Paraboloids are surfaces that resemble a parabola rotated around an axis. They can be classified as either elliptic paraboloids or hyperbolic paraboloids.

The equation of an elliptic paraboloid is:

$$ \frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 2z $$

The equation of a hyperbolic paraboloid is:

$$ \frac{x^2}{a^2} - \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 2z $$

For example, this equation defines an elliptic paraboloid: $$ \frac{x^2}{4} + \frac{y^2}{9} = 2z $$

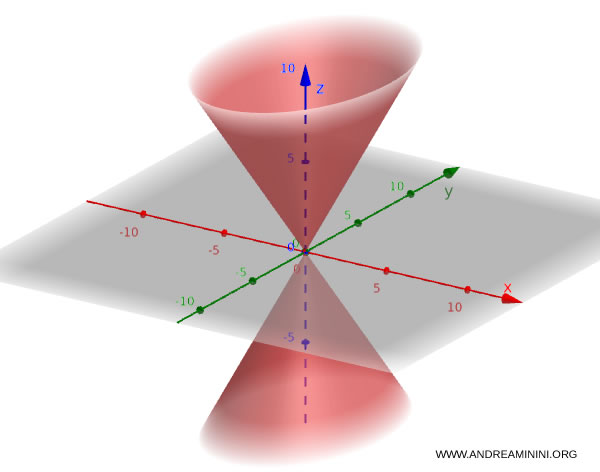

Cone

A cone has its vertex at the origin and extends infinitely in both directions along its axis. Its typical equation is:

$$ \frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} - \frac{z^2}{c^2} = 0 $$

For instance, this equation defines a cone: $$ \frac{x^2}{4} + \frac{y^2}{9} - \frac{z^2}{16} = 0 $$

Cylinder

A cylindrical surface is formed by straight lines (called generators) that run parallel to a fixed axis.

When the surface’s equation involves only two variables (e.g. $x^2 - y - 1 = 0$), its solutions trace out a curve in the corresponding plane (for instance, the Oxy plane), known as the directrix.

Sliding this curve along the free axis (such as the z-axis) generates the entire cylindrical surface.

The shape of the directrix determines the type of cylinder:

- if it’s a parabola, the cylinder is parabolic

- if it’s an ellipse, the cylinder is elliptical

- if it’s a circle, the cylinder is circular

- if it’s a hyperbola, the cylinder is hyperbolic

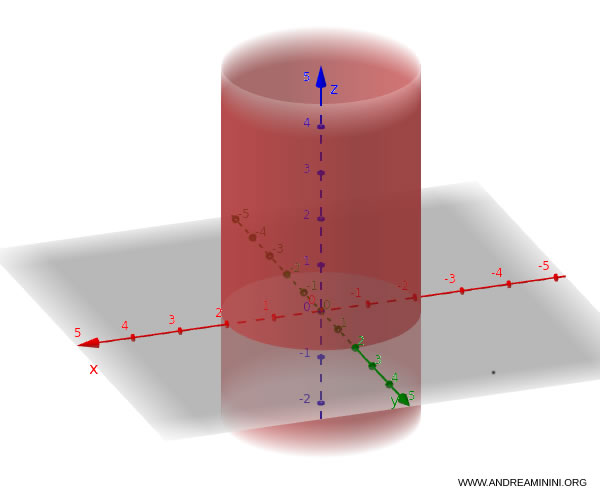

The equation of a circular cylindrical surface is typically written as:

$$ x^2 + y^2 + a x + b y + c = 0 $$

Notice that there’s no $z$ term because the surface extends infinitely along the $z$ axis.

This equation represents a circular cylinder provided that the coefficients meet the following condition:

$$ \frac{a^2}{4} + \frac{b^2}{4} - c \ge 0 $$

In other words, this ensures that the directrix in the xy-plane is indeed a circle.

The same logic applies to the other coordinate planes, xz and yz, whenever the equation involves variables $x$ and $z$ or $y$ and $z$, respectively.

Example. Here’s a practical example of a circular cylinder in three-dimensional space: $$ \frac{x^2}{4} + \frac{y^2}{4} = 1 $$ This equation defines a circular cylindrical surface.

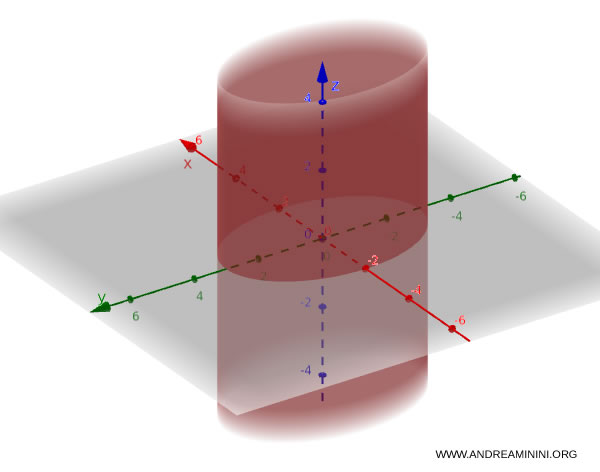

The equation of an elliptical cylinder is given by:

$$ \frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1 $$

When the coefficients satisfy $ a = b $, the cylinder has a circular cross-section.

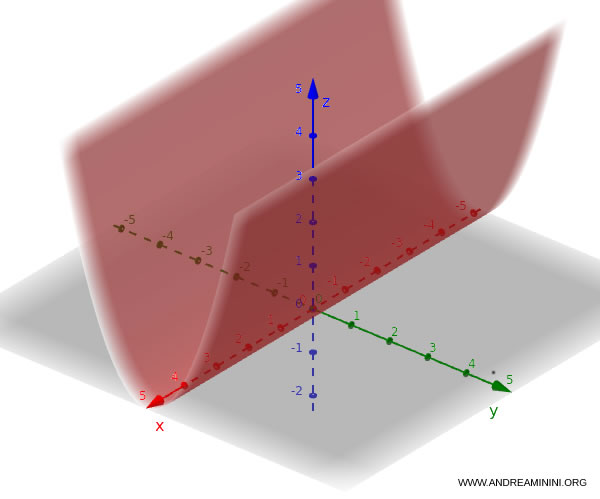

Example. Here’s a practical example of a cylinder in three-dimensional space: $$ \frac{x^2}{4} + \frac{y^2}{9} = 1 $$ This equation describes a cylinder whose cross-section is an ellipse.

The equation of a hyperbolic cylinder is:

$$ \frac{x^2}{a^2} - \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1 $$

This equation holds for all values of $z$, defining a hyperbolic cylindrical surface whose axis runs parallel to the $z$ axis.

Example. Here’s an example of a hyperbolic cylinder: $$ \frac{x^2}{2} - \frac{y^2}{4} = 3 $$ In this case, the directrix is a hyperbola in the xy-plane, and the generator lines run parallel to the y-axis.

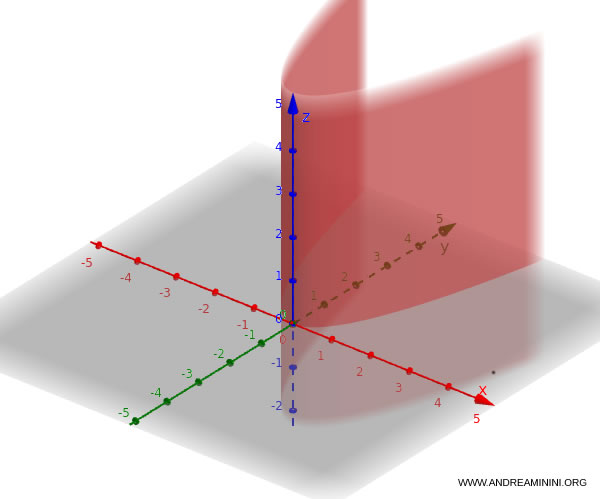

The equation of a parabolic cylinder takes the form:

$$ y = k x^2 $$

If this relationship holds for all values of $z$, it defines a parabolic cylindrical surface with its axis parallel to the $z$ axis.

Example. Consider the directrix: $$ y = x^2.$$ The resulting parabolic cylindrical surface can be described as $ y = x^2, \quad z \in \mathbb{R} $.

This equation is often written in implicit form as either: $$ y - x^2 = 0 $$ or $$ x - y^2 = 0 $$ If the equation instead involves $x$ and $z$, it becomes: $$ z = x^2 $$ representing a parabolic cylinder whose axis is parallel to $y$.

If it involves $y$ and $z$: $$ z = y^2 $$ In this case, it defines a parabolic cylinder whose axis runs parallel to $x$.

These examples show how all these different types of quadrics can be expressed through second-degree equations, each yielding a distinct geometric surface in three-dimensional space.

Cross-Sections of Surfaces

To study the curves formed by intersecting a surface with a plane, we can impose constraints by setting $z$ or $y$ to specific values.

For example, consider the ellipsoid:

$$ \frac{x^2}{9} + \frac{y^2}{4} + \frac{z^2}{1} = 1 $$

If we set $z = 0$, we obtain:

$$ \frac{x^2}{9} + \frac{y^2}{4} = 1 $$

The result is an ellipse in the $xy$-plane, representing a cross-section of the ellipsoid.

Curve as the Intersection of Two Surfaces

A curve can be defined as the intersection of two surfaces in three-dimensional space. $$ \begin{cases} F(x, y, z) = 0 \\ G(x, y, z) = 0 \end{cases} $$

In other words, the set of all points whose coordinates $(x, y, z)$ satisfy both equations simultaneously generally forms a curve in space.

The analytical description of such a curve is given precisely by this system:

$$

\begin{cases}

F(x, y, z) = 0 \\

G(x, y, z) = 0

\end{cases}

$$

This is known as the implicit representation of the curve because it doesn’t express $x, y,$ and $z$ explicitly in terms of a parameter.

Example

Consider the system defined by these two surfaces:

$$

\begin{cases}

x^{2} - y + z - 1 = 0 \\

x^{2} + 2y + z - 1 = 0

\end{cases}

$$

The intersection of these surfaces is the curve consisting of all points that satisfy both equations at once.

It’s often convenient to parametrize the curve to make it easier to analyze or plot.

Let’s introduce a parameter $ t $ and set:

$$ x = t $$

We then equate the two surface equations to solve for $ y $:

$$ x^{2} - y + z - 1 = x^{2} + 2y + z - 1 $$

Subtracting one from the other gives:

$$ x^{2} - y + z - 1 - \bigl(x^{2} + 2y + z - 1\bigr) = 0 $$

Which simplifies to:

$$ -3y = 0 $$

So:

$$ y = 0 $$

Next, we substitute $ x = t $ and $ y = 0 $ into one of the original equations to solve for $ z $:

$$ x^{2} + 2y + z - 1 = 0 $$

$$ t^2 + 2 \cdot 0 + z - 1 = 0 $$

Which leads to:

$$ z = 1 - t^2 $$

Therefore, the curve of intersection can be expressed by the following parametric equations:

$$

\begin{cases}

x = t \\

y = 0 \\

z = 1 - t^{2}

\end{cases}

$$

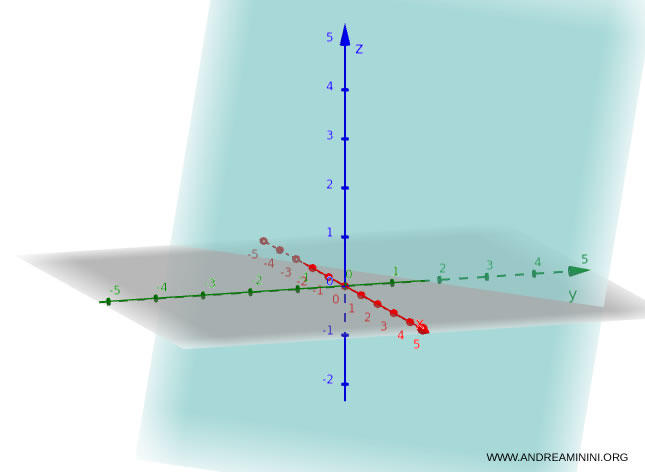

This makes it easy to visualize the curve in GeoGebra using the Curve command:

Curve(t, 0, 1 - t^2, t, -5, 5)

And so on.