Equation of a Line

The explicit form of the line equation is $$ y = mx + q $$ where m is the slope and q is the y-intercept, indicating where the line intersects the y-axis.

This is called the explicit form because the variable y is expressed as a function of the variable x.

$$ y = mx + q $$

Here, y is the dependent variable while x is the independent variable.

As the slope m changes, the inclination of the line changes.

As the y-intercept q changes, the line's intersection with the y-axis changes.

Thus, the explicit form of the line equation can represent any line in the plane except those parallel to or coinciding with the y-axis.

The case of lines parallel to or coinciding with the y-axis

For the y-axis, a different equation is used:

$$ x = 0 $$

For lines parallel to the y-axis, the equation x=k is used:

$$ x = k $$

Note. The y-axis cannot be represented with the explicit form y=mx+q because the slope (m) is undefined for a perfectly vertical line.

There are no values for the slope (m) and the y-intercept (q) that can be substituted into the equation y=mx+q to represent a vertical line. For this reason, any line parallel to the y-axis is given by the equation $$ x = k $$ By varying k, you get all lines parallel to the y-axis for any value of y. For k=0, you get the y-axis.

The Implicit Form of the Equation

The implicit form of the line equation is another way to represent lines in the plane: $$ ax + by + c = 0 $$ where a, b, and c are real numbers called coefficients. It is also known as the general form of the line equation.

In the implicit form, neither x nor y is expressed as a function of the other.

By varying the coefficients a, b, and c, the implicit form can represent any line in the Cartesian plane.

Note. The coefficients a and b in the implicit equation ax + by + c = 0 cannot both be zero.

The implicit form can also represent lines parallel to or coinciding with the y-axis.

This is why it is also called the general form of the line equation.

Note. To represent a vertical line, set b=0 and solve for x:

$$ ax + by + c = 0 $$

$$ ax + 0 \cdot y + c = 0 $$

$$ ax + c = 0 $$

$$ x = - \frac{c}{a} $$

Proof

Consider two points P1(x1, y1) and P2(x2, y2) in the Cartesian plane through which a line r passes, and a point P(x, y) between P1 and P2 on the line.

Project the points onto the x and y axes using two sets of parallel lines.

The set of vertical lines, colored in blue, parallel to the y-axis, intersect two transversals: the line r and the x-axis.

Therefore, according to the Thales' theorem, the corresponding segments on the transversals are directly proportional to each other.

$$ \frac{ \overline{P_1P} }{ \overline{AB} } = \frac{ \overline{P_1P_2} }{ \overline{AC} } $$

$$ \frac{ \overline{P_1P} }{ \overline{P_1P_2} } = \frac{ \overline{AB} }{ \overline{AC} } $$

Similarly, the set of horizontal lines, colored in red, parallel to the x-axis, intersect two transversals: the line r and the y-axis.

Again, according to Thales' theorem, the corresponding segments on the transversals are directly proportional to each other.

$$ \frac{ \overline{P_1P} }{ \overline{DE} } = \frac{ \overline{P_1P_2} }{ \overline{DF} } $$

$$ \frac{ \overline{P_1P} }{ \overline{P_1P_2} } = \frac{ \overline{DE} }{ \overline{DF} } $$

From these two proportions, I deduce the equality between the ratios AB/AC=DE/EF

$$ \frac{ \overline{P_1P} }{ \overline{P_1P_2} } = \frac{ \overline{AB} }{ \overline{AC} } = \frac{ \overline{DE} }{ \overline{DF} } $$

That is

$$ \frac{ \overline{AB} }{ \overline{AC} } = \frac{ \overline{DE} }{ \overline{DF} } $$

Knowing that AB = x - x1 and AC = x2 - x1

$$ \frac{ x - x_1 }{ x_2 - x_1 } = \frac{ \overline{DE} }{ \overline{EF} } $$

Also, knowing that DE = y - y1 and DF = y2 - y1

$$ \frac{ x - x_1 }{ x_2 - x_1 } = \frac{ y - y_1 }{ y_2 - y_1 } $$

This last relation is called the collinearity condition of three points on a line.

With some algebraic manipulation, I modify the previous relation.

$$ ( x - x_1 ) \cdot ( y_2 - y_1 ) = ( y - y_1 ) \cdot ( x_2 - x_1 ) $$

$$ x \cdot ( y_2 - y_1 ) - x_1 \cdot ( y_2 - y_1 ) = y \cdot ( x_2 - x_1 ) - y_1 \cdot ( x_2 - x_1 ) $$

$$ x \cdot ( y_2 - y_1 ) - x_1 \cdot ( y_2 - y_1 ) - y \cdot ( x_2 - x_1 ) + y_1 \cdot ( x_2 - x_1 ) = 0 $$

$$ \require{cancel} x \cdot ( y_2 - y_1 ) - y \cdot ( x_2 - x_1 ) - x_1 y_2 + \cancel{ x_1 y_1 } + x_2 y_1 - \cancel{ x_1 y_1 } = 0 $$

$$ x \cdot ( y_2 - y_1 ) - y \cdot ( x_2 - x_1 ) - x_1 y_2 + x_2 y_1 = 0 $$

I transform -y( x2 - x1 ) into the equivalent form +y( x1 - x2 )

$$ x \cdot ( y_2 - y_1 ) + y \cdot ( x_1 - x_2 ) - x_1 y_2 + x_2 y_1 = 0 $$

At this point, I set a = ( y2 - y1 ), b = ( x1 - x2 ), c = - x1 y2 + x2 y1

$$ x \cdot a + y \cdot b + c = 0 $$

In this way, I obtain the implicit form of the line equation.

$$ ax + by + c = 0 $$

How to Convert from Implicit to Explicit Form

To convert the implicit form $ ax + by + c = 0 $ to the explicit form $ y = mx + q $, simply solve for y.

$$ y = - \frac{ax}{b} - \frac{c}{b} $$

$$ y = - \frac{a}{b} \cdot x - \frac{c}{b} $$

Where -a/b is the slope and -c/b is the y-intercept.

$$ m = - \frac{a}{b} $$

$$ q = - \frac{c}{b} $$

This is only possible if the coefficient b is not zero.

Note. Converting from implicit to explicit form is not possible if b=0, because it involves division by zero.

Example

Consider the implicit form of a line equation where a=3, b=6, and c=9

$$ 3y + 6x + 9 = 0 $$

To convert it to the explicit form, solve for y in terms of the other variables.

$$ 3y = - 6x - 9 $$

Then apply the invariant property by dividing both sides of the equation by 3

$$ \frac{3y}{3} = - \frac{6}{3}x - \frac{9}{3} $$

$$ y = - 2x - 3 $$

This final form is the line equation in explicit form.

$$ y = mx + q $$

Where the slope is m=-2 and the y-intercept is q=-3

What is the difference between the implicit and explicit forms? Both forms represent the same line in the plane. The difference lies in the algebraic representation.

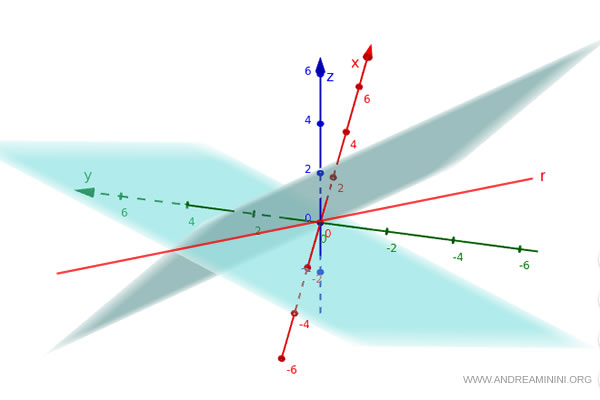

Implicit form of a line as the intersection of two planes

Any line in three-dimensional space can be described as the intersection of two non-parallel planes, represented by a system of two linear equations: $$ \begin{cases} a_1 x + b_1 y + c_1 z + d_1 = 0 \\ \\ a_2 x + b_2 y + c_2 z + d_2 = 0 \end{cases} $$

In analytic geometry, a line in space (within $\mathbb{R}^3$) can be represented in several different ways.

One of the simplest is the so-called implicit form, which expresses the line as a system of two plane equations.

Each plane in space is defined by a general equation:

$$ a x + b y + c z + d = 0 $$

If we take two distinct, intersecting planes, their system of equations can be written as:

$$

\begin{cases}

a_1 x + b_1 y + c_1 z + d_1 = 0 \\ \\

a_2 x + b_2 y + c_2 z + d_2 = 0

\end{cases}

$$

These are known as the general equations of the line, with each equation representing one of the planes.

This system defines the line implicitly, by imposing two conditions on the points $(x, y, z)$. The points that satisfy both equations lie on both planes at once - that is, they form the intersection of the two planes.

The intersection of two distinct (non-parallel) planes is precisely a line $ r $.

Of course, the system representing the line is not unique, since infinitely many different pairs of planes can intersect to produce the same line $ r $.

The set of all planes that contain the same line $ r $ is called a pencil of planes.

Why is it called the implicit form? It’s called implicit because it doesn’t explicitly express the coordinates of the line as functions of a parameter, nor does it immediately reveal whether the line passes through a given point or what its direction is. Instead, it defines the line through two constraints (the two planes), with the line emerging as their intersection.

Example

Let’s consider the following two planes:

$$

\begin{cases}

x + y + z - 1 = 0 \\

2x - y + 3z + 4 = 0

\end{cases}

$$

The set of points $(x, y, z)$ that satisfies both equations forms a line in space.

Line Equations in Two-Variable Form

This method describes a line in three-dimensional space by expressing two of its coordinates as functions of the third.

For instance, you can express \( x \) and \( y \) in terms of \( z \):

$$ \begin{cases} a_1 x + b_1 y + c_1 z + d_1 = 0 \\ \\ a_2 x + b_2 y + c_2 z + d_2 = 0 \end{cases} \ \rightarrow \ \begin{cases} x = g z + p \\ \\ y = h z + q \end{cases} $$

Or express \( x \) and \( z \) as functions of \( y \):

$$ \begin{cases} x = k y + r \\ \\ z = j y + s \end{cases} $$

Or express \( y \) and \( z \) as functions of \( x \):

$$ \begin{cases} y = m x + t \\ \\ z = n x + u \end{cases} $$

This representation provides an implicit parametrization of the line, without introducing an explicit parameter like \( t \).

By assigning arbitrary values to the independent variable (say, \( z \)), you can generate specific points lying on the line.

Note. The choice of which variable to use as the parameter depends on the line’s orientation in space. For example, if the line is parallel to the \( xy \)-plane, then the \( z \)-coordinate remains constant along the line. In that case, \( z \) cannot serve as a parameter because it doesn't vary. $$ \begin{cases} x = g z + p \\ \\ y = h z + q \end{cases} $$ The same logic applies if the line is parallel to the \( xz \)- or \( yz \)-plane - in those cases, you can’t choose \( y \) or \( x \) respectively, since those coordinates remain fixed. So when expressing a line this way, always choose a variable that actually changes along the line.

Example

Let’s consider the line defined by the system:

$$ \begin{cases} x + y - z = 0 \quad \text{(1)} \\ 2x - y + 3z = 5 \quad \text{(2)} \end{cases} $$

We'll find a two-variable form of this line by solving the system for \( x \) and \( y \) in terms of \( z \).

Start by adding the two equations to eliminate \( y \):

$$ \begin{cases} x + 2x + y - y - z + 3z = 0 + 5 \\ 2x - y + 3z = 5 \end{cases} $$

$$ \begin{cases} 3x + 2z = 5 \\ 2x - y + 3z = 5 \end{cases} $$

Solve the first equation for \( x \):

$$ \begin{cases} x = \frac{5 - 2z}{3} \\ 2x - y + 3z = 5 \end{cases} $$

Now substitute this expression for \( x \) into the second equation and solve for \( y \):

$$ \begin{cases} x = \frac{5 - 2z}{3} \\ 2 \left( \frac{5 - 2z}{3} \right) - y + 3z = 5 \end{cases} $$

$$ \begin{cases} x = \frac{5 - 2z}{3} \\ \frac{10 - 4z}{3} - y + 3z = 5 \end{cases} $$

Isolate \( y \):

$$ \begin{cases} x = \frac{5 - 2z}{3} \\ y = \frac{10 - 4z}{3} - 5 + 3z \end{cases} $$

$$ \begin{cases} x = \frac{5 - 2z}{3} \\ y = \frac{10 - 4z - 15 + 9z}{3} \end{cases} $$

Which simplifies to:

$$ \begin{cases} x = \frac{5 - 2z}{3} \\ y = \frac{5z - 5}{3} \end{cases} $$

These are the two-variable equations that define the line. Any valid algebraic method can be used to solve the system - here, adding the equations provided a convenient approach.

Fractional and Parametric Equations of a Line

Given two distinct points $A(x_1, y_1, z_1)$ and $B(x_2, y_2, z_2)$, the line passing through these points can be described by the following fractional equations: $$ \frac{x - x_1}{l} = \frac{y - y_1}{m} = \frac{z - z_1}{n} $$ where: $$ l = x_2 - x_1, \quad m = y_2 - y_1, \quad n = z_2 - z_1 $$ The values $l, m, n$ are known as the direction ratios of the line.

Fractional equations provide a concise way to represent a line in three-dimensional space, as they capture in a single expression how the coordinates $x, y,$ and $z$ vary along the line.

We already know that the condition for three points to be collinear in space can be expressed as:

$$ \frac{ x - x_1 }{ x_2 - x_1 } = \frac{ y - y_1 }{ y_2 - y_1 } = \frac{ z - z_1 }{ z_2 - z_1 } $$

We define the denominators in this relationship as $ l = x_2 - x_1 $, $ m = y_2 - y_1 $, and $ n = z_2 - z_1 $.

$$ \frac{ x - x_1 }{ l } = \frac{ y - y_1 }{ m } = \frac{ z - z_1 }{ n } $$

These quantities $l, m, n$ are referred to as direction ratios and indicate how much each coordinate changes along the $x$, $y$, and $z$ axes when moving from one point on the line to another.

- $l = x_2 - x_1$ represents the change in the $x$ coordinate from $A$ to $B$.

- $m = y_2 - y_1$ represents the change along the $y$ axis.

- $n = z_2 - z_1$ represents the change along the $z$ axis.

The numbers $l, m, n$ essentially describe how the line extends through space in each direction.

In other words, the vector $(l, m, n)$ is the direction vector of the line - it indicates the precise direction and orientation in which the line proceeds through space.

Note. If you multiply the direction ratios by the same nonzero scalar $k$, the line’s direction remains unchanged. In other words, the vectors $(l, m, n)$ and $(k\,l, k\,m, k\,n)$ determine the same line. Therefore, two lines are parallel if their direction ratios are proportional, i.e., $ l = k\,l' $, $ m = k\,m' $, and $ n = k\,n' $, meaning the following proportions hold: $$ \frac{l}{l'} = \frac{m}{m'} = \frac{n}{n'} = k $$

Example

Consider the points:

$$ A(1, -2, 3), \quad B(5, 4, 1) $$

Let’s compute the direction ratios:

$$ l = 5 - 1 = 4 $$

$$ m = 4 - (-2) = 6 $$

$$ n = 1 - 3 = -2 $$

The fractional equations of the line passing through $A$ and $B$ are:

$$ \frac{x - 1}{4} = \frac{y + 2}{6} = \frac{z - 3}{-2} $$

This fractional equation tells us that for every increase of $l$ in $x$, there’s a corresponding increase of $m$ in $y$, and a change of $n$ in $z$.

Each fraction indicates how many times the direction vector has been traversed starting from point $A$.

In this case, the direction vector has components $ \vec{v} = (4, 6, -2) $.

Case of Zero Coefficients. If any of the direction ratios $l, m, n$ equals zero, it means the line runs parallel to one of the coordinate planes:

- If $l = 0$, the line is parallel to the $Oyz$ plane, so $x$ remains constant.

- If $m = 0$, the line is parallel to the $Oxz$ plane, so $y$ remains constant.

- If $n = 0$, the line is parallel to the $Oxy$ plane, so $z$ remains constant.

In such cases, fractional equations cannot be written because this would involve division by zero. Instead, we use simplified equations where the constant coordinate is stated explicitly.

Parametric Equations

If we set all three fractions equal to a single parameter $t$, we get the system:

$$ \begin{cases} \frac{x - x_1}{l} = t \\ \frac{y - y_1}{m} = t \\ \frac{z - z_1}{n} = t \end{cases} $$

Solving each equation for $x$, $y$, and $z$ gives:

$$ \begin{cases} x - x_1 = l\,t \\ y - y_1 = m\,t \\ z - z_1 = n\,t \end{cases} $$

$$ \begin{cases} x = x_1 + l\,t \\ y = y_1 + m\,t \\ z = z_1 + n\,t \end{cases} $$

These are known as the parametric equations of the line.

Hence, the fractional equations can be viewed as an alternative representation of the same parametric equations.

Example

Let’s take the fractional equation from the previous example:

$$ \frac{x - 1}{4} = \frac{y + 2}{6} = \frac{z - 3}{-2} $$

We can rewrite this as a system by setting all fractions equal to a parameter $t$:

$$ \begin{cases} \frac{x - 1}{4} = t \\ \\ \frac{y + 2}{6} = t \\ \\ \frac{z - 3}{-2} = t \end{cases} $$

Solving for $x$, $y$, and $z$ yields:

$$ \begin{cases} x = 1 + 4\,t \\ \\ y = -2 + 6\,t \\ \\ z = 3 - 2\,t \end{cases} $$

These are the parametric equations of the same line.

Polar Coordinates of a Line

- The equation of a line can also be written using polar coordinates.

- If the line passes through the origin, it is enough to know the angle α that determines the slope $$ m = \tan \alpha \ \ \ \ with \ \alpha \ne \frac{\pi}{2} + k \pi $$

- If the line does not pass through the origin, it is necessary to know the distance d between the line and the pole (origin) and the angle β of the segment d relative to the positive polar axis. $$ d = r \cdot \cos (\theta) $$

Where θ is the angle of the polar coordinates of any other point P on the line.

Notes

Here are some observations and remarks on the linear equation (the equation of a line).

- The equation of a line identifies all points on that specific line

This statement can be proven by contradiction. Assume there is a point P'(x;y') outside the line r that satisfies the linear equation ax+by+c=0 for line r. By this assumption, point P' has the same x-coordinate as point P but a different y-coordinate.

According to this assumption, both of the following equations are satisfied: $$ ax+by+c=0 $$ $$ ax+by'+c=0 $$ To solve this system, I use the reduction method and subtract one equation from the other: $$ \begin{matrix} ax & +by & + c & =0 & - \\ ax & +by' & + c & = 0 & \\ \hline 0 & +b(y-y') & 0 & = 0 \end{matrix} $$ This results in the equation $$ b(y-y')=0 $$ Since the coefficient b is not zero, the only way to satisfy this equation is if y=y'. In other words, the external point P' must have the same y-coordinate as the internal point P. However, this contradicts our initial assumption that P' is outside the line, while P is on the line. Therefore, it is false that points outside a line r satisfy the equation ax+by+c=0. Consequently, only the points on the line r satisfy the linear equation ax+by+c=0. - Every linear equation corresponds to a line, and vice versa

Every linear equation in two variables x and y corresponds to a line on the Cartesian plane, and every line corresponds to such an equation. $$ r \Leftrightarrow ax+by+c=0 $$Proof. Knowing that the coefficients "a" and "b" in the equation cannot both be zero, let's examine two extreme cases: a=0 and b≠0, and a≠0 and b=0. In the first case, we get an pencil of parallel lines to the x-axis, while in the second case, we get a bundle of lines parallel to the y-axis.

In the intermediate case where both coefficients are non-zero, i.e., a≠0 and b≠0, the linear equation remains in the form $ ax+by+c=0 $. I need to prove that this equation corresponds to a specific line on the Cartesian plane. Consider three points on the line given by the equation (x1;y1), (x2;y2), (x3;y3), and set them up in a system. $$ \begin{cases} ax_1+by_1+c=0 \\ ax_2+by_2+c=0 \\ ax_3+by_3+c=0 \end{cases} $$ Using the reduction method, I subtract the third equation from the first and second equations. $$ \begin{cases} a(x_1-x_3)+b(y_1-y_3)=0 \\ a(x_2-x_3)+b(y_2-y_3)=0 \end{cases} $$ $$ \begin{cases} a(x_1-x_3)=-b(y_1-y_3) \\ a(x_2-x_3)=-b(y_2-y_3) \end{cases} $$ $$ \begin{cases} \frac{x_1-x_3}{y_1-y_3}= - \frac{b}{a} \\ \frac{x_2-x_3}{y_2-y_3}= - \frac{b}{a} \end{cases} $$ Comparing the two equations, we see they are both equal to -b/a. Therefore, I can write the following equality: $$ \frac{x_1-x_3}{y_1-y_3}= \frac{x_2-x_3}{y_2-y_3} $$ which is equivalent to the alignment condition of three points on a line $$ \frac{x_1-x_3}{x_2-x_3}= \frac{y_1-y_3}{y_2-y_3} $$ This proves that the linear equation $ ax+by+c=0 $ corresponds to one and only one line on the plane, establishing a one-to-one correspondence between the solutions of the linear equation and the points on a line on the plane.

And so on.